Lipstick in Government: Brazil’s Inadequate Gender Quota

By Alexia Rauen, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF version of this article, click here.

Rocky Transition from Rousseff to Temer

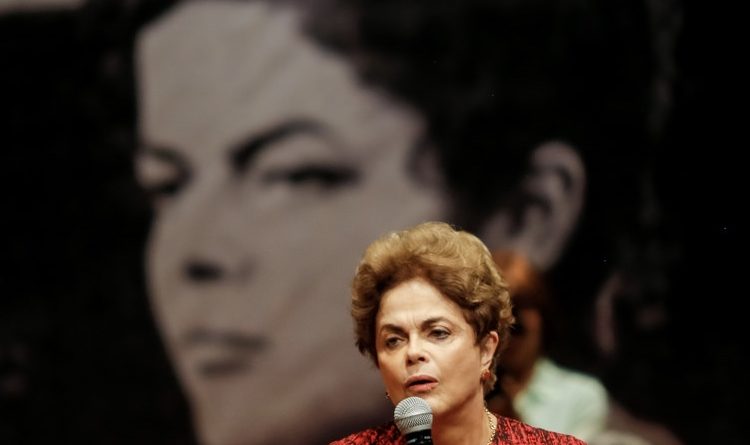

Whether accurate or not, it has become commonplace to judge the success of women’s rights in a country by its willingness to accept a female head of state. Brazil elected its first female president, Dilma Rousseff, in 2011. Dilma Rousseff was problematically impeached in August of 2016 and replaced by her Vice President, Michel Temer.[i]

Temer rapidly made drastic changes to the Rousseff government which he inherited. He reduced the size of the cabinet and stocked it entirely with men. Additionally, he dismissed the only Afro-Brazilian member of the cabinet,[ii] even though half of the nation identifies itself as “black or mixed race.”[iii] As Temer’s cabinet reflects no female or ethnic representation, this new cabinet finds itself under a great deal of scrutiny. Brazil’s Supreme Court has now called for investigations into eight cabinet members, including the chief of staff, on the grounds of corruption.[iv] Additionally, seven other ministers have been linked to the Carwash corruption investigations.[v] The Temer administration may not be able to serve a full term in office, but concerns that the country has taken a step backward are valid. The choice of cabinet and politically motivated impeachment of Rousseff worries Brazilian constituents desiring the orderly progression of female political rights.[vi] Feminists throughout Brazil have argued that Rousseff’s removal was sexist in nature, stating that similar accusations towards male politicians have historically been overlooked.[vii] Rousseff herself has spoken out about the persistent discrimination against women in Brazil, and her disappointment in Temer’s “government of rich old white men.”[viii]

Gender Quota Legislation

Brazil’s current legislature has only 51 female representatives, out of 513 total members.[ix] In an attempt to improve female representation in government, gender quotas were introduced in 1995.[x] Brazilian federal gender quota legislation is applicable to all political parties and defines an appropriate percentage of each gender in government. The goal of gender quota legislation is to increase the number of female legislators serving in the Brazilian congress.

Quota legislation is typically implemented after women’s rights movements apply significant pressure. In Brazil, as was the case in Mexico,[xi] female politicians demanded inclusivity.[xii] In Brazil’s case, this relatively small number of female politicians formed a group, known as the “lipstick caucus,” in an effort to advance women’s rights and achieve the desired gender quotas.[xiii] Aside from quota legislation, this pioneer group of women achieved numerous legislative victories. These included improved length of maternity and paternity leaves, equal pay between the sexes, and freedom from gender discrimination, among others.[xiv] It is truly remarkable the progress pushed forward by this group of female legislators. While these women were able to bring quota legislation to fruition in Brazil, an underlying issue remains. Unfortunately, in the country, gender quotas have had a minimal effect and few repercussions exist if they remain unfulfilled.[xv]

Brazil’s legislation states that the percentage of male or female candidates for congressional seats must fall between 30 and 70 percent.[xvi] If a party fails to comply, perhaps by creating a list with only 20 percent women, then some men may be removed from a party’s list to compensate.[xvii] However, women will not be added to the list. Therefore, being caught in violation changes percentages not by incorporating more women, but by removing some male candidates.[xviii] Moreover, parties often fail to fulfill the 30 percent requirement.[xix] Rather than making tangible improvements to the quota system, Brazil’s government has chosen to increase the number of possible candidates on a party’s list, allowing a party to legally present a list that is 150 percent of the legislative positions available.[xx] For example, if there are 100 legislative positions to be filled, 150 candidates can be proposed by a single party. Rousseff’s political party, the Brazilian Workers’ party (PT), claims to uphold the federal 30 percent quota, but does not strongly implement this policy in practice.[xxi]

Built-in Constraints: Brazil’s Political System

Female representation is affected by the nature of the Brazilian political system. Brazil possesses an electoral system in which voters can choose to vote for either a political party or a specific candidate, but can only vote for one of these options.[xxii] There is a minimum number of votes, called a threshold, that must be reached for a party to win a place in the legislature.[xxiii] To decide these positions, votes are combined between the individual candidates and the party votes.[xxiv] Therefore, a list with many candidates can increase the overall cumulative vote total. This type of voting incentivizes larger candidate lists, as does the fact that more candidates can be registered than there are positions legally available. Due to the structure of the political system, women in Brazil have been used as a means to acquire more party votes; however, at the end of the elections, male candidates are the party’s leading candidates and are appointed to legislative positions.[xxv] Furthermore, this Brazilian system is considered open-list, since voters may choose to vote for any candidate on a given list.[xxvi] In contrast, a closed-list system may allow for more female candidates to be elected, if females are listed at the top of the party’s ballot. In Argentina, females in political parties hold more sway than in Brazil, and have increased female representation by requiring that lists alternate names by gender.[xxvii]

From 1997 to 2010, the “Americas” region accounted for the most significant increase in female representatives than in any other area in the world.[xxviii] Argentina boasts the first of Latin America’s gender quotas, implemented in 1991.[xxix] Argentina also possesses the highest percentage of female legislators in Latin America at 38.5 percent.[xxx] Moreover, Argentina’s quotas hold stricter penalties, as parties that do not comply with the 30 percent female representation requirement will not have their list approved and their candidates will not be able to run in elections.[xxxi]

For Brazilian women to progress politically, the Brazilian quota system needs to be enforced with harsher penalties for noncompliance, and the premise of overflow candidates must be abolished. Brazil’s quota system is not up to par with other Latin American nations, and will be unlikely to increase female political involvement. Furthermore, regulations on campaign funding in Brazil leave much to be desired. Brazil only requires parties to dedicate five percent of their funding to increasing female participation within the party.[xxxii] These funds are relatively inadequate and are unlikely to make any significant difference in balancing genders in the legislature. Current enforcement policies are insufficient and will do little to motivate parties to comply to gender quotas.

The Disease of Machismo

Luís Inácio Lula da Silva, known for his close relationship with his successor Dilma Rousseff, had a presidency marked by increased inclusion of women.[xxxiii] Lula da Silva promised to improve the situation of women’s rights in Brazil during his presidential campaign, and created the Special Secretariat for Policies for Women, an official ministry to propose improvements in women’s rights directly to the president.[xxxiv] This ministry continued under Rousseff,[xxxv] but was reportedly removed by Temer.[xxxvi] There have been no updates to the ministry website since March of 2016,[xxxvii] which still lists the former president of the organization, Eleonora Menicucci, who was appointed by Rousseff.[xxxviii] Evidently, Temer’s government marks a particularly low point for female representation as well as women’s rights in Brazil.

The expansion of women’s rights in Brazil continues to be plagued by a machista society that prioritizes men over women in the political sphere.[xxxix] This is not to say influential feminists have not made progress. Bertha Lutz, a Brazilian feminist, is attributed with playing an instrumental role in the creation of the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women.[xl] As Temer takes steps backwards, Brazilian women must push forward. With the 2018 elections around the corner, feminists in Brazil must continue to take action in demanding female inclusivity. They have been the cornerstone of change in the past and are the key to progress in the future.

By Alexia Rauen, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Additional editorial support provided by Aline Piva, Research Fellow and Head of Brazil Unit at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs, Mark Langevin, Senior Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs, Taylor Lewis, Extramural Contributor at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs, and Sharri K Hall, Tobias Fontecilla, Laura Schroeder, and Erika Quinteros, Research Associates at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Featured Image: Presidenta Dilma Rousseff durante Ato em Defesa da Democracia. (Brasília – DF, 24/08/2016) Taken from: Flickr, Roberto Stuckert Filho/PR

[i] Romero, Simon, “Dilma Rousseff Is Ousted as Brazil’s President in Impeachment Vote,” August 31, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/01/world/americas/brazil-dilma-rousseff-impeached-removed-president.html.

[ii] Koren, Marina, “Who’s Missing From Brazil’s Cabinet?” May 25, 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2016/05/brazil-cabinet-rousseff-temer/483372/.

[iii] Romero, Simon. “New President of Brazil, Michel Temer, Signals More Conservative Shift,” May 12, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/13/world/americas/michel-temer-brazils-interim-president-may-herald-shift-to-the-right.html?_r=0.

[iv] Brito, Ricardo and Lisandra Paraguassu, “Brazil judge orders corruption probe into a third of Temer’s cabinet,” April 11, 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-politics-probes-idUSKBN17D2KB.

[v] “Dos 24 Ministros de Temer, 15 Sao Paolo Investigados o Citados NA Lava Jato,” October 17, 2016, http://www.brasil247.com/pt/247/poder/260736/Dos-24-ministros-de-Temer-15-s%C3%A3o-investigados-ou-citados-na-Lava-Jato.htm.

[vi] Gomes dos Santos, Pedro de Abreu, “Gender Representation: Parties, Institutions, and the Under-Representation of Women in Brazil’s State Legislatures, (PhD diss., University of Kansas, 2012).

[vii] Hao, Ani, “In Brazil, women are fighting against the sexist impeachment of Dilma Rousseff,”The Guardian, July 5, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/jul/05/in-brazil-women-are-fighting-against-the-sexist-impeachment-of-dilma-rousseff.

[viii] Leahy, Joe, “Dilma Rousseff: ‘A woman in authority is called hard, while a man is called strong,’” Financial Times, December 8, 2016, https://www.ft.com/content/cd5c2b24-bc05-11e6-8b45-b8b81dd5d080.

[ix] “Brazil,” Quota Project, accessed May 15, 2017, http://www.quotaproject.org/country/brazil.

[x] Gomes dos Santos, Pedro de Abreu, “Gender Representation: Parties, Institutions, and the Under-Representation of Women in Brazil’s State Legislatures, (PhD diss., University of Kansas, 2012).

[xi] Baldez, Lisa, “Primaries vs. Quotas: Gender and Candidate Nominations in Mexico, 2003,” http://sites.dartmouth.edu/lisabaldez/files/2012/11/Baldez_LAPS_Fall07.pdf.

[xii] Gomes dos Santos, Pedro de Abreu, “Gender Representation: Parties, Institutions, and the Under-Representation of Women in Brazil’s State Legislatures, (PhD diss., University of Kansas, 2012).

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] “A bancada do batom e a Constituicao cidada,” Congreso Em Foco, October 31, 2013, http://congressoemfoco.uol.com.br/opiniao/colunistas/a-bancada-do-batom-e-a-constituicao-cidada/.

[xv] “Brazil,” Quota Project, accessed May 15, 2017, http://www.quotaproject.org/country/brazil.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] Gomes dos Santos, Pedro de Abreu, “Gender Representation: Parties, Institutions, and the Under-Representation of Women in Brazil’s State Legislatures, (PhD diss., University of Kansas, 2012).

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] “Brazil,” Quota Project, accessed May 15, 2017, http://www.quotaproject.org/country/brazil.

[xxii] Cheibub, José Antonio, “Brazil: Candidate-Centered PR in a Presidential System,” Ace Project, accessed May 16, 2017, http://aceproject.org/ace-en/topics/es/esy/esy_bo.

[xxiii] Ibid.

[xxiv] Ibid.

[xxv] Gomes dos Santos, Pedro de Abreu, “Gender Representation: Parties, Institutions, and the Under-Representation of Women in Brazil’s State Legislatures, (PhD diss., University of Kansas, 2012).

[xxvi] Cheibub, José Antonio, “Brazil: Candidate-Centered PR in a Presidential System,” Ace Project, accessed May 16, 2017, http://aceproject.org/ace-en/topics/es/esy/esy_bo.

[xxvii] “The Implementation of Quotas: Latin American Experiences,” International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (paper presented on workshop at Lima, Peru, February 23-24, 2003).

[xxviii] Gomes dos Santos, Pedro de Abreu, “Gender Representation: Parties, Institutions, and the Under-Representation of Women in Brazil’s State Legislatures, (PhD diss., University of Kansas, 2012).

[xxix] Kang, Alice and Alli Tripp, “Gender Quotas: Female Legislative Representation,” Spring 2009, http://www.americasquarterly.org/node/544.

[xxx] Gomes dos Santos, Pedro de Abreu, “Gender Representation: Parties, Institutions, and the Under-Representation of Women in Brazil’s State Legislatures, (PhD diss., University of Kansas, 2012).

[xxxi] “Argentina,” Quota Project, accessed May 16, 2017, http://www.quotaproject.org/country/argentina.

[xxxii] “Brazil,” Quota Project, accessed May 15, 2017, http://www.quotaproject.org/country/brazil.

[xxxiii] “The Implementation of Quotas: Latin American Experiences,” International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (paper presented on workshop at Lima, Peru, February 23-24, 2003).

[xxxiv] “National Plan of Policies for Women,” Special Secretariat for Policies for Women, February

2005, http://www.spm.gov.br/sobre/publicacoes/publicacoes/2004/plano_ingles.pdf.

[xxxv] “Atual composição do CNDM,” Secretaria Especial de Políticas para as Mulheres, March 23,

2016, http://www.spm.gov.br/assuntos/conselho/composicao.

[xxxvi] Koren, Marina, “Who’s Missing From Brazil’s Cabinet?” May 25, 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2016/05/brazil-cabinet-rousseff-temer/483372/.

[xxxvii] “Atual composição do CNDM,” Secretaria Especial de Políticas para as Mulheres, March 23,

2016, http://www.spm.gov.br/assuntos/conselho/composicao.

[xxxviii] “Ex-ministra Eleonora Menicucci critica condenação: ‘Ataque a todas as mulheres,’ Rede Brasil Atual, May 5, 2015, http://www.redebrasilatual.com.br/cidadania/2017/05/ex-ministra-eleonora-menicucci-critica-condenacao-ataque-a-todas-as-mulheres

[xxxix] Gomes dos Santos, Pedro de Abreu, “Gender Representation: Parties, Institutions, and the Under-Representation of Women in Brazil’s State Legislatures, (PhD diss., University of Kansas, 2012).

[xl] Marino, Katherine. “The heritage of Latin American women’s political empowerment,” August 2, 2012, http://gender.stanford.edu/news/2012/heritage-latin-american-women%E2%80%99s-political-empowerment.