From Rafael Correa to Lenín Moreno: Ecuador’s Swing to the Right

An On-The-Ground Report

By Charles G. Ripley, Ph.D.

When I landed in Ecuador on December 7th, 2016, the country was in full swing for its presidential election, to be held on February 19th, 2017. The official candidate, Lenín Moreno, served as vice president (2007-2013) and as the United Nation’s Special Envoy on Disability and Accessibility (2013-2016) under President Rafael Correa (2007-2017). Condemned to a wheelchair after being shot in an attempted robbery in 1998, Moreno was a perfect fit for the latter position, and as vice president significantly increased budgetary spending on those with disabilities. At the end of the campaign, Moreno squeaked out a victory with roughly 51% of the vote compared to Guillermo Lasso’s 49%, the center-right candidate. Moreno’s victory was largely attributed to the support of Correa’s base, made up largely of the popular sectors, the millions who have benefited from the Citizens Revolution, and parts of the Ecuadorian intelligentsia. It was a titanic victory for Correa’s party PAIS Alliance (el Movimiento Alianza PAIS). For the Citizen Revolution (La Revolución Ciudadana), the name of the country’s post-neoliberal socially-oriented movement, it served as a defeat for the rise of the right, which continues to take place throughout South America. The neo-liberal economic approach, which emphasizes a relaxation of workers’ rights, the privatization of state industries, the free flow of international c apital, and cuts in education and other social programs, lost. It was a moment of celebration.

Arriving again three years later, the irony was palpable. Correa’s base had lost and the center-right grew triumphant. Everyone expected Moreno to be his own person, but few if anyone expected such a right turn. In addition to the controversial revocation of Julian Assange’s asylum status in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London, Moreno has reversed most of Correa’s progressive policies, many of which helped decrease poverty from 37.6% to 22.5% and create unprecedented growth, averaging 4.3% between 2006 and 2014. The GINI coefficient, a measure of inequality, fell as well, from .54 to .47. The country also witnessed its longest period of political stability in recent memory. These descriptive statistics are not from some lefty blog, but the World Bank itself, no amigo of leftist movements.[1] With such a successful period in Ecuadorian history, what exactly happened?

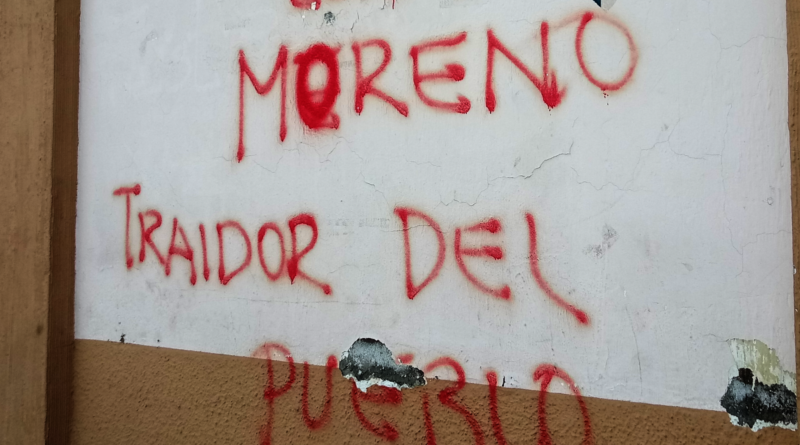

The common narrative legitimated by the Ecuadorian right-wing and the U.S. government, which is elated to witness this conservative renewal, is that Moreno is bringing back democracy and improving relations with the United States and foreign investors. This caricature is a very seductive myth. Reading Correa’s tweets about Moreno being a “traitor,” as well as endless stories of how Correa aimed to control the press, the restoration of democracy and improving relations abroad are appealing tales.[2] Conservative leaders are singing and re-singing these claims until they become unchallenged truths. As Brazilian President Jair Messias Bolsonaro (2019 – present) stated before the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, “Nowadays, you have a [Brazilian] president who is a friend of the United States who admires this beautiful country.”[3] This is completely false. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003 – 2011) enjoyed a productive relationship with Washington, even attracting praise from the arch-conservative Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld (2001-2006).[4]

A similar myth is being touted about Argentine Presidents Néstor Carlos Kirchner (2003-2007) and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (2007-2015) now that center-right Mauricio Macri (2015-present) won the executive branch. “I think after going through the Kirchner period [the governments led by Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner],” Benjamin Gedan, former Director for the South America division in the National Security Council and current director for Woodrow Wilson’s Argentina Project, oddly states, “it is hard to change the perception of Argentina overnight, as it was for a very long period.”[5] Gedan devotes no attention to the fact that Kirchner oversaw the greatest economic and social development in Argentina’s recent history, even prompting former President George W. Bush (2001-2009) to praise his Argentine counterpart: “The economy has changed in quite dramatic fashion, thanks to wise decisions you have made. So congratulations for dealing with a difficult circumstance and making decisions that have improved the lives of your people.”[6] A similar problem is panning out in Venezuela. Although the current government of Nicolás Maduro (2013-present) is accused by the US government and other anti-Chavismo organizations of human rights violations, little to nothing is said of those committed by the conservative opposition, which are more egregious.[7]

Conscious of all the propaganda against left-leaning Latin American movements, I traveled back to Ecuador in April of 2019. I wanted to witness firsthand what was happening in this Andean nation of roughly 17 million people. I found that the switch has little to do with restoring democracy, improving the economy, or putting the country on a “path from populism to moderation.”[8] In fact, foreigners with whom I spoke, many retirees, were impressed with the country’s development. “When I first got here, there was little around,” a retiree from the Netherlands said. “We used to go to Colombia and think it was developed,” he recalled, “now Ecuador is more developed.” Hearing positive comments about Correa’s presidency was interesting since retirees tend to be of the conservative nature. Despite many conceding there was corruption in his government, most foreigners and locals alike confess there was stunning economic growth. Even Washington D.C. newspapers admit Correa was grossly popular.[9]

Rafael Correa was elected president at a difficult time. The country was unstable and severely wracked by mismanagement and corruption. When he took over the executive branch in 2007, the previous decade witnessed a quick succession of ten presidents. The country was in recession and the dollarization of the economy in 2000 served as a last ditch attempt to save an ailing economy.[10] But his career in Ecuador began earlier. Armed with a PhD in economics from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, President Luis Alfredo Palacio González (2005-2007) tapped Correa as the Minister of Economics and Finance in 2005. After disagreeing with conditionality of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Correa quit the position in protest, lasting not even a year. The conditionality policies of the IMF were widely unpopular, prompting massive street protests throughout various administrations.[11] Launching a presidential campaign in 2006 under the center-left umbrella party Alianza País, Correa defeated his main rival Álvaro Fernando Noboa with 57% percent of the vote. The country was in the mood for a change.

During his ten-year presidency (he ran three times), the government initiated a slew of successful progressive policies. Correa luxuriated in a time of the commodity boom. Opposed to allowing a neoliberal free-for-all, however, Correa demanded more royalties and greater transparency from the corporations.[12] In fact, he pushed for the controversial Mining Law (Ley Minera) in 2009 to attract foreign direct investment during the commodity boom, contradicting arguments that the government was against investment.[13] In turn, Correa was able to dedicate this new windfall of money to efficient social programs to address the country’s rampant poverty. He expanded el Bono de Desarrollo Humano, for example, a program that funneled resources to the most vulnerable Ecuadorians, not only the poor, but also the disabled. A university study found that this initiative significantly improved the lives of the most vulnerable Ecuadorians.[14] He further doubled social spending on a broad array of areas, including health, education, and housing.[15]

Pro-growth and pro-poor policies were not limited to mere governmental subsidies. The government enacted important banking regulation. It expanded “solidarity-based” financial lending (cooperatives, savings and loans, among other social and economic lending), initiated financial stimuli during times of recession, and enacted capital controls to earn money and disincentive capital flight.[16] Capital flight is a titanic problem in developing countries and Ecuador has found that the economy had lost up to $30 billion in previous decades. Correa understood this and enacted various laws to address this perennial economic problem with financial regulation.[17] He further supported workers’ rights, particularly those of maids (trabajadoras domésticas), who he included in the labor laws to protect their rights and fair minimum wage.[18]

Another pivotal policy area was education reform. My interviews with educators found that Correa aimed to professionalize the education system. In addition to increasing primary education spending to 5% of GDP, the president worked to set strict guidelines on educational standards. In 2012, up to fourteen “garage universities” (universidades de garage) were closed due to low standards and fraudulent behavior. Such garage universities are common throughout Latin America. They are not well regulated and lack any genuine educational credentials. Living in Nicaragua for eight years (2000-2008, I witnessed their growth when neoliberal governments (after the Sandinistas left office in 1990) lifted educational regulations. Correa wanted to address this problem early on. He was able to close a number of them down, ruffling the feathers of the investor elite who had profited from the low standard higher educational system. He also increased educational expectations, requiring university rectors to have PhDs.[19]

In the end, Correa’s policies helped Ecuador develop, far beyond the commodities boom. An in-depth research on the Correa years by economists Mark Weisbrot, Jake Johnston and Lara Merling conclude that the following policies benefited the country: “ending central bank independence, defaulting on illegitimate debt, taxing capital leaving the country, countercyclical fiscal policy, and ― in response to the most recent oil price crash ― tariffs implemented under the WTO’s provision for emergency balance of payments safeguards.”[20] This post-neoliberal model proved to be fruitful, which challenged the Washington Consensus.[21]

With such success, why would the United States be against Correa to begin with? The U.S. government demands pliant leaders (regardless of how brutal) who support its regional hegemony. Correa, on the other hand, did not see Ecuador’s relation to Washington as one of subordination. In 2007, he kicked out the U.S. military base in Manta. “We’ll renew the base on one condition: that they let us put a base in Miami,” the president stated, “an Ecuadorian base.”[22] He ceased transactions with the World Bank in the same year.[23] Correa also defied the United States and European Union by granting asylum to Julian Assange in its Embassy. The Ecuadorian elite, many with ties to powerful figures in Washington, detested Correa as well. The most egregious case was Roberto and William Isaias, two brothers wanted for bank fraud. Fleeing Ecuador and making it to the United States, they were able to buy influence with generous donations to prominent senators and even President Barack Hussein Obama (2009-2017) himself.[24] In foreign policy, he remained close to South American leftists such as Venezuelan President Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías (1999-2013) and even hosted the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), an alternative regional organization that excluded the United States and Canada. Such initiatives were seditious for Washington. Generally speaking, the United States has the tendency to look down on Latin America as well, its perennial backyard. William K. Black astutely points out how the New York Times offers more favorable coverage of Italy’s former Prime Minister (2011-2013) and Minister of Economy and Finance (2011-2012) Mario Monti than that of Correa (2007-2017). “The New York Times treat[s] Monti reverentially and Correa dismissively.” Black concludes, despite Correa being much more successful.

Moreno has done his utmost to undo much of Correa’s legacy. In addition to the controversy surrounding Julian Assange, he has laid off loads of workers, slashed gas subsidies, and relaxed financial regulations. Much of the professionalization of education—from doctoral degree demands to the closure of garage universities—have been eliminated. The president even made a $4.2 billion loan agreement with the dreaded IMF. His economic policies of structural readjustment have hurt working class Ecuadorians and produced a backlash in the form of country-wide protests.[25] The president even was forced to change his Minister of Economics, which is now dominated by the conservatives who voted against him.[26] The response was quite brutal, even imprisoning protesters and closing down media outlets.[27] Since Moreno is now an ally of the United States, any abuses go unheard in the OAS, much like those of Colombian President Iván Duque Márquez (2018-present). Witnessing a student protest, I was shocked at the repression carried out by the Colombian police and riot squad.

Foreign policy has also experienced a shift to the right. Moreno shuttered the UNASUR building and has curried favor with very conservative presidents. Although it is important that Ecuador maintain cordial relations with South American countries, he removed the statue of UNASUR’s first Secretary General Néstor Kirchner (2010), oddly declaring, “he did not represent the values of our people.”[28] Kirchner was democratically elected president of Argentina, and stepped down after one term. But ironically, Moreno has supported Brazil’s Bolsonaro, a controversial figure who tramples on social rights and celebrates Brazil’s brutal military dictatorship (1964-1985).

Of course, the ten years of governance under Correa were not perfect. There are legitimate complaints of authoritarian proclivities and mismanagement, not to mention environmental problems related to the mining initiatives.[29] Nonetheless, Ecuador’s new shift to the right with austerity measures, deregulation, and the erosion of workers’ rights may not bode well for the future. When President Moreno opened the country to the IMF and the institutions’ concomitant policies, he claimed, “Our government is recovering its credibility.” Only time will tell.

——————-

End notes

[1] The World Bank in Ecuador. 2019. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/ecuador.

[2] For an example of anti-Correa conservatism, see Stuenkel, Oliver. “After Correa, Ecuador’s Moreno Is Struggling to Offer His Own Vision.” Americas Quarterly. February 27, 2019. https://www.americasquarterly.org/content/ecuadors-moreno-overcoming-correas-legacy-struggles-articulate-his-own-vision.

[3] Fox, Ben. “Brazil’s far-right president visits CIA on friendly US tour.” Associated Press. March 18, 2019. https://www.apnews.com/9e097b1cb92c4400b76c096da8f26910

[4] “Rumsfeld praises Lula and warns Venezuela.” MercoPress. March 24, 2005. https://en.mercopress.com/2005/03/24/rumsfeld-praises-lula-and-warns-venezuela.

[5] Del Carril, Santiago. ‘“Argentina is a vital partner of the United States.”’ Buenos Aires Times. March 3, 2018. https://www.batimes.com.ar/news/argentina/argentina-is-a-vital-partner-of-the-united-states-and-we-should-do-what-we-can-to-help-this-model.phtml

[6] The Whitehouse: President George W. Bush. “President Bush Meets with President Kirchner of Argentina.” Office of the Press Secretary. Nov. 4, 2005. https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2005/11/20051104.html

[7] For an objective scientific analysis of human rights violations in Venezuela, see Ripley, Charles. “Venezuela, violence, and the New York Times: failing when it comes to selective indignation.” COHA. Sept. 18, 2017. https://coha.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Charles-RIpley-NYT-Merged.pdf.

[8] Lifted from the neoliberal Economist, this quote helps solidify the myth, though the article offers little evidence into its main argument. “Lenín Moreno’s new economic policy.” Economist. April 11, 2019. https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2019/04/13/lenin-morenos-new-economic-policy.

[9] Miroff, Nick. “Ecuador’s popular, powerful president Rafael Correa is a study in contradictions.” The Washington Post. March 15, 2014. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/ecuadors-popular-powerful-president-rafael-correa-is-a-study-in-contradictions/2014/03/15/452111fc-3eaa-401b-b2c8-cc4e85fccb40_story.html?utm_term=.c826e6c9462f.

[10] See Ripley, Charles. “Exchange Rate Policy Options for South America: Making the Case for Flexibility.” Latin America Policy 1 no. 2 (December, 2010): 244-263. Wang, Sam. “Examining the Effects of Dollarization on Ecuador.” COHA. July 26, 2016. https://coha.org/examining-the-effects-of-dollarization-on-ecuador/#_ftn3.

[11] See Rowland, Aaron Thomas. “How Left a Turn? Legacies of the Neoliberal State in Latin America.” PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2013. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2475.

[12] “Ecuador negocia alto porcentaje de regalías mineras.” El Universal. August 6, 2011. https://www.eluniverso.com/2011/08/06/1/1356/ecuador-negocia-contratos-mineros-obtener-53-renta-mineria-II.html

[13] For more on this controversial policy, see Dosh, Paul and Nicole Kligerman. “Correa vs. movimientos sociales: conflicto en Ecuador.” NACLA. Dec. 15, 2009. https://nacla.org/article/correa-vs-movimientos-sociales-conflicto-en-ecuador

[14] Coloma Atiencia, Victor Marcelo and Karina Anabelle Ascensio Burgos. “Bono de desarrollo humano y su incidencia en la calidad de vida de los beneficiarios en Guayaquil.” Tesis, la Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, 2018. https://dspace.ups.edu.ec/bitstream/123456789/15575/1/UPS-GT002134.pdf

[15] Mark Weisbrot, Jake Johnston, and Lara Merling. “Decade of Reform: Ecuador’s Macroeconomic Policies, Institutional Changes, and Results.” CEPR. Feb. 2017. http://cepr.net/publications/reports/decade-of-reform-ecuador-s-macroeconomic-policies-institutional-changes-and-results.

[16] Ibid.

[17] See Smith, Stanfield. “Ecuador’s Accomplishments under the 10 Years of Rafael Correa’s Citizen’s Revolution.” COHA. April 17, 2017. https://coha.org/ecuadors-accomplishments-under-the-10-years-of-rafael-correas-citizens-revolution/. Weisbrot, Mark. “Media can’t ignore financial scandal in Ecuador’s presidential election.” The Hill. March 23, 2017. https://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/international/325442-media-cant-ignore-financial-scandal-in-ecuadors-presidential.

[18] Enríquez, Carolina. “10 medidas laborales en nueve años.” El Comercio. May 1, 2016. https://www.elcomercio.com/actualidad/medidaslaborales-salariobasico-trabajadores-rafaelcorrea-leyes.html.

[19] For education reform, consult Ayala, Maggy. “Secretario de Educación de Ecuador explica cierre de 14 universidades.” El Tiempo. April 21, 2012. https://www.eltiempo.com/archivo/documento/CMS-11626041.

[20] Weisbrot, Mark, Jake Johnston, and Lara Merling. “Decade of Reform.”

[21] For more on the Washington Consensus, See Ripley, Charles G. “Pathways to Peace, Progress, and Public Goods:

Rethinking Regional Hegemony.” PhD Diss, Arizona State University, 2013. https://repository.asu.edu/attachments/110339/content/Ripley_asu_0010E_12710.pdf.

[22] Stewart, Phil. “Ecuador wants military base in Miami.” Reuters. Oct. 22, 2007. https://uk.reuters.com/article/ecuador-base/ecuador-wants-military-base-in-miami-idUKADD25267520071022.

[23] Weitzman, Hal. “Ecuador expels World Bank envoy.” Financial Times. April 27, 2007. https://www.ft.com/content/2c845102-f4e3-11db-b748-000b5df10621.

[24] It is common that wealthy elites begin to exert pressure against Latin American center-left governments since they tend to step on the elites’ interests. For the special case cited above, see Robles, Francis. “Wanted by Ecuador, 2 Brothers Make Mark in U.S. Campaigns.” New York Times. March 11, 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/12/world/americas/wanted-by-ecuador-2-brothers-make-mark-in-us-campaigns.html.

[25] For Moreno’s economic policies, consult “His economic policies of structural readjustment has hurt the working class.” CELAG. June 23, 2018. https://www.celag.org/nueva-ley-economica-en-ecuador-una-bomba-de-tiempo/.

[26] “Lenín Moreno cambia de ministro de Economía.” Notimérica. May 16, 2018. https://www.notimerica.com/politica/noticia-lenin-moreno-cambia-ministro-economia-medio-problemas-economicos-sufre-ecuador-20180516174402.html.

[27] “10 detenidos en marcha contra la orden de prisión para Rafael Correa.” El Comercio. July 5, 2018. https://www.elcomercio.com/actualidad/detenidos-marcha-rafaelcorrea-ordendeprision-casobalda.html. “La policía reprime marcha correísta contra las políticas de Lenín Moreno.” NODAL. April 17, 2019. https://www.nodal.am/2019/04/la-policia-reprime-marcha-correista-contra-las-politicas-del-gobierno/. “Portal Ecuador Inmediato denunció «cierre» por órdenes del Ejecutivo (+Comunicado).” April 23, 2019. https://ecupunto.com/2019/04/23/portal-digital-de-ecuador-inmediato-fue-cerrado-por-ordenes-del-ejecutivo-nacional-comunicado/.

[28] “Edificio de la Unasur pasará a manos de la Universidad Indígena del Ecuador.” ECUPunto. March 14, 2019. https://ecupunto.com/2019/03/14/edificio-de-la-unasur-pasara-a-manos-de-la-universidad-indigena-del-ecuador/.

[29] For information into some controversies, see Zibell, Matías. “Tras 10 años de gobierno, además de un Ecuador dividido, ¿qué más deja Rafael Correa?”, BBC. May 24, 2017. https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-38980926.