Chile: An Adolescent Democracy Heads to the Polls

By Roland Benedikter, Senior Research Fellow, and Miguel Zlosilo, Extramural Contributor, at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

For a PDF of this article, click here.

Due to time constraints, this piece has not undergone COHA’s normal editing procedures and reflects the personal view of the author.

In November 2017, the–mostly juvenile–candidates of the “Miss Chile” competition revolted against what they described as a patriachial system in a patriarchal country. Many domestic observers coined the word of a still “adolescent nation” mirrored in such protest. The soul-searching came just weeks before the November 19 presidential and general elections. It coincided with another event perceived as symbolic: the elimination of Chile’s proud national soccer team La Roja (The Red) from the upcoming world championships 2018 in Russia. La Roja were the 2015 and 2016 Copa Amèrica champions and ranked as the 3rd national team in the world in 2016. As polls in November showed, a majority of Chilean voters perceived both events as symbols of an overall unsatisfying development of the nation under the current government of Michelle Bachelet. The media and intellectuals took these events as opportunity to debate the still “juvenile” character of Chile’s democracy and the many fallacies still inherent in its political and social system as a protracted effect of the nation’s authoritarian and divisive past, as described by historians such as Alfredo Jocelyn-Holt, Gabriel Salazar and Arturo Valenzuela. In their view, the path of the outgoing government shows that the nation’s political culture is still developing, and its transition to an “adult” democracy still not fully completed.

The Mood Leading Up To The Elections

In the weeks preceding the elections, various nation-wide polls carried out by the country’s leading research institutes converged in drawing a disappointing image of Bachelet’s second tenure since March 11, 2014. It has been a constant feature of the Chilean democratic process that new presidents get a large bonus in public confidence and voter approval that they lose fast and reach a record disapproval about one year before the next elections. The popular support rate then once again increases when the president leaves office, drawing a curve with the landmarks “messiah” first, “crook” then to eventually end with “in retrospect, the guy was not so bad”. This typical “adolescent” mood curve of Chilean voters regularly starts with exaggerated enthusiasm and greatest expectations just to be over-proportionally disappointed shortly thereafter, thus mirroring the historic relation of post-dictatorship Chileans (since 1988) to democracy as such. The result has been a constant change of course given that democratic elections since the 1990s have provided frequent changes between leftist and rightist alliances. The zig-zag course have led to a pattern of development where every new government has ideologically replaced its predecessor and steered the country in the opposite direction, thus nullifying previous achievements. Although there were some exceptions such as the presidency of Ricardo Lagos and the first tenure of Michelle Bachelet, the Chilean pattern of regular (and predictable) disillusion over any given presidency has been constantly reflected either in overall voter approval or in the combination of popular views on the nation’s growth and its social redistribution with the perception of specific fields such as education, the health care system and welfare.

In the case of Bachelet, the typically “adolescent” mood curve of the Chilean public has been particularly harsh. Bachelet left her first presidency (2006-10) in March, 2010, with a record popular support of 84 percent, according to polls by the Santiago-based poll institutes Adimark GfK, CEP Chile and CADEM. At the start of her second tenure in March 2014, Bachelet had an approval rate of 65 percent, which decreased to 24 percent one and a half years later and finished at 21 percent in August 2017. The respective curve of disapproval developed from 29 percent in July 2014 to a historical high of all presidents since 2000 finishing at 56 percent rejection in August 2017. While this pattern was similar to her predecessor–and now once again potential successor–Sebastián Piñera Echenique, it was particularly striking that the approval of Bachelet’s second tenure precipitated immediately after the start of her charge like never before in democratic Chilean history, and in sharp contrast to her first tenure. According to Adimark Gfk (http://www.adimark.cl/estudios/documentos/42_gobierno_agosto_2017_ok.pdf), CEP Chile (https://www.cepchile.cl/cep/site/artic/20170831/asocfile/20170831165004/encuestacep_jul_ago2017.pdf) and CADEM (http://www.cadem.cl/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Track-PP-195-OctS1-VF.pdf), in July and August 2017 69 percent of Chileans were of the opinion that the nation was in a state of stagnation, while just 16 percent believed that it was progressing and 14 percent saw it in decline That was the most negative percentage of all recent presidents. Moreover, the approval of how Bachelet ran her government decreased from the highest level of 58 percent in June 2014 to the lowest rate of just 19 percent in August 2016, slightly growing again over her last year in tenure to arrive at 35 percent in August 2017. In sum, public opinion polls shortly before the elections revealed an unambiguous discontent of the Chilean society with Bachelet’s politics, as well as with most parts of the political system.

“Juvenile” Voter Mood Mirrored In A Disruptive Political Culture

As usual in post-dictatorship Chile, the mood curve of voters was reflected in the development within the governing political alliance. Chilean leftist and rightist party alliances use to start with great pathos, just to present serious cracks between their constitutent groups shortly thereafter, and to dissolve after a given period of time first informally, then sometimes de facto. Afterward, everbody is used to speaking of a “wasted opportunity”. In the framework of such tradition, Bachelet’s mandate was a constant struggle against her governing alliance’s fast dissolution by forging compromises over daily problems and putting up a brave front on it. That led to a succession of lukewarm positions which could not satisfy neither the political nor the public sphere, since they were in stark contrast to the bold moves promised. Although the underlying mechanism may often be simplified as being a typical motive of political culture in the “Global South”, Chile’s recent history has been a continuous exemplification of the principle of an “adolescent” democratic habitat. In it, on the one hand, formal political processes are constantly paralleled by often more important informal personal, group and family interrelations which behind closed doors cross alliances and parties to forge compromises and thus constantly undermine both voter will and the legitimacy and reputation of the political sphere. On the other hand, the coexistence of institutional and para-institutional processes leads to the constant threat of disruption of political will and the failure of objectives. The result is a political process that in Chile since the 1990s has consistenly been a dangerous course to steer between the Skylla of programs and visions based on reforms and new beginnings and the Charybdis of behind-the-doors compromise outside the institutions, with frequent dilutions of programs and the disillusion of the public as the usual outcome.

When Disillusion Becomes Chronic

All five main periods usually discerned in Chile’s recent history follow this pattern–and it is highly questionable if any new government after the one of Bachelet II will be able to break the cycle. Chile’s recent history is a history of socio-political identity crises. Period one (1970-1973) was the crisis of the Latin American socialist identity. It consisted in the truncated process of social transformation that was represented by the Salvador Allende project of a democratic way to socialism in times of the Cold War. Period II (1974-1990) was the failure of the neoliberal promise. It consisted in the political, economic and social failure of the neoliberal socio-economic project implemented mainly by the use of force by Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship. Period III (1990-2010) consisted in a basic (and lasting) disillusion with democracy: Joy did not come. The period consisted in the discovery that the return to democracy itself did not represent a better future for many, and that it was an inadequate promise that the imbalances of the neoliberal model would be corrected subsequently at the political, economic and labor levels. The pattern of this period included the first term of Michelle Bachelet (2006-2010), although Bachelet ended her charge with high levels of approval. Period IV (2010-2014) consisted in Chile’s (re)turn to the right. It refers to the popular disillusion with the messianic promise of billionaire Sebastián Pinera that efficiency and the fresh air of alternating power would allow (the government) to increase the efficiency of the state apparatus, for example in the educational and health care sectors, banish social problems such as crime, and generate employment via economic growth. And the most recent, fifth period of Michelle Bachelet’s second term (2014-present) could be branded best as: Everything was just for your enjoyment. This slogan refers to the despair generated by the second Bachelet government in face of the failure of a structural reform project that came down mainly by indigenous elements, while the same could not be said of the Allende and Pinochet periods.

Reasons For Bachelet’s Failure: Non-Achievement Of Reform Goals

Without doubt, it wasn’t exactly tailwind to accompany the process of reform promised by Bachelet at the start of her tenure in 2014. The fall of copper prices and the temporary stagnation of emerging economies, combined with a hesitant recovery of major global trade partners of the Chilean economy, did not help. However, most domestic analysis tends to show that the failure of Bachelet’s second political project was due to internal problems, mainly, not to external influences. There was a constant crisis of Bachelet’s reform project, both with regard to popular support and concerning the political unity of her alliance at the institutional level. That does not mean that her efforts generate no partial success and symbolic legacy in the fields of specific matters, such as gender emancipation and the environment.

The judgment of the majority of Chilean academics, the media and intellectuals that Bachelet’s second government has failed is based on the breach of her five fundamental promises:

- A tax reform that intended to reduce inequality and collect 3 percent of the GDP to finance free education for all without slowing down economic growth.

- An educational reform that pretended to end profit in education, provide universal free education and improve its quality toward internationalization.

- A constitutional reform that pretended to elaborate a new constitution (Magna Charta) with the strong participation of the Chilean civil society and in full respect of current institutions.

- A labor market reform that pretended to end the growing asymmetry between the spending and economic power of employers and workers, in addition to promoting unionization.

- A pension reform that intended to increase pensions via a better inter-generational solidarity structure and to introduce the government as an actor in the pension market hoping that this would increase competition, lower systemic costs and improve benefits for pensioners.

How and why did these reform goals fall short of the expectations?

- Bachelet’s tax reform did not achieve the goals established by her coalition, the leftist Nueva Mayoría (New Majority). It was quickly modified and in its half-hearted form was believed to be one origin of the stagnant growth of the economy. The tax reform was widely criticized due to the complexity of its application, particularly by SMEs. Before the reform passed the congress, it polled higher approval than disapproval rates. Afterwards the trend reversed and rejection was twice as high as consent rates.

- The educational reform failed to offer universal free education for all students. It did not eliminate the profit-making in higher education, and it did not introduce concrete measures to improve the quality of education. It was objected by the Chilean Council of Rectors and by the main private universities. The evaluation of the educational reform displays various fluctuations. After several protests marches in 2015 the disapproval rate reached 70 percent with a peak of 72 percent shortly after Bachelet’s Higher Education Reform in 2016. In 2017, rejection declined to 52 percent.

- The constitutional reform failed to generate an official document which included the agreements achieved in the town councils that were held. The constituent process and concrete form of the promised Magna Charta were never clarified. The reform process failed to define a strategy to generate substantial changes in the constitution and was not able to specify the legal form of carrying them out.

- Bachelet’s labor reform left the unions, i.e. part of their own votership and governing majority, with little pleasure. The reform translated into deep disputes over the legitimacy of leadership. It criticized the business community and the SME, the first because of its profits and the second because of the disparity in the tax treatment between companies, SMEs and workers. Even the leaders of the unions said that the reform was tailored to suit the needs of the banks rather than to benefit the largest part of the people. Public consent of the labor reform was constantly declining until the end of 2016, when it started to grow again moderately.

- Finally, the pension reform failed to become a bill, despite the persistence of the executive in getting it out. The maximum achievement in the matter was the report of the so-called Bravo Commission, which failed to reach full consensus among those in favor of adjusting the system via an increase in the retirement age and the introducation of a so-called solidarity pillar, including private pension insurance. The project also failed because of the lack of clear political will to move the project forward. The pension reform project revealed steady higher rates of public disapproval than approval.

A Historical Opportunity Wasted

In the months before the November elections, the shortfalls of Bachelet’s second government to materialize the reforms she could have achieved in a historically non-adverse situation were compared to the wasted opportunity of the Chilean national team, which in the eyes of Chile’s soccer fans in October 2017 squandered the chance to mark a milestone in the history of Chilean football by reaching the final round of three consecutive world championships for the first time. Bachelet’s second government was blamed by the media and intellectuals for committing a series of critical strategic errors, namely:

Bachelet did not capitalize on the 20 percent winning margin she achieved in the second round of the presidential elections in December 2013 to move forward with her reform project. She did not properly prepare the approval of her structural reforms having an unprecedented majority in both chambers. She committed serious errors in the selection of her main collaborators at the level of ministers and advisors, including the involvement of her son Sebastián Dávalos and his wife, Natalia Compagnon, in a real-estate corruption scandal involving parts of the political and financial elite. She underestimated the opposition’s communication capacity to generate public rejection towards her main reforms, particularly against the educational reform. She was unable to align the governing coalition around her reformist political project in an enduring manner. Critics saw the results of all these defaults not only at the social, but also at the macroeconomic level, where during Bachelet’s second mandate Chile’s neighbor Peru outperformed the nation in direct foreign investment, threatening Chile’s dominant position in the copper market, i.e. the commercial basis of Chile’s wealth. Was it a coincidence then that it was exactly the national football team of Peru to eliminate La Roja from the World Championship?

Chile’s public opinion reacted as usual. Bachelet’s approval paradoxically increased with her mandate coming to an end, after having reached all-time lows during her second presidency.

An Insufficient Self-Evaluation

The self-evaluation of Bachelet in face of the November elections has been rather self-complacent and out of touch with reality. Over the past months, Bachelet has tried to lower the profile of doubts about the level of achievement of her charge. As her most important achievements, she mentioned progress in social housing and kindergardens for vulnerable people and what she described as qualitative progress of the health care system. As she stated (http://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-41517480), “one of the achievements that many women have celebrated is that we have passed the law of decriminalization of the termination of pregnancy for three reasons [in cases of rape, when the fetus is nonviable or the mother’s life is at risk].” When asked if she had some self-criticism regarding her mandate, Bachelet answered, “Maybe we have been very ambitious to aspire to such deep and encompassing reforms within just four years. We had not always the chance to show the successes and benefits that these reforms will produce, and I was not always well understood… We also had an opposition that did not give us a honeymoon from the first day on, but all this is part of life. As people say: we should not cry in politics.”

Yet the clarity of Bachelet’s analysis on the causes of her downward popularity and reform failure raise questions as to whether the elements mentioned by her were foreseeable. If so, this would imply a lack of self-criticism concerning the level of preparation for the legislative process of her main reforms. The lack of preparation, this time in the sense of elimination of dangers, includes the corruption scandal involving her son, which cost her the decisive time to implement her reforms but which was referred to by Bachelet simply as “this is under investigation, I do not want to comment on it”.

Toward Another Change Of Course?

Overall, compared with its aspirations and voter expectations, the second Bachelet government failed, partially or totally, depending on how and where one wants to look. Like Bachelet, one can see the glass half full, or as her critics half empty. Yet there is broad consensus that the level of achievement of the objectives designated by Bachelet herself at the start of her tenure is debatable. Regardless of the attribution of weight to the different causes of failure, the constant shortfall of the socio-political reform process as such, including the overall blueprint for a balanced “country project”, has been a constant at various historical moments triggered by different factors, endogenous and exogenous. Apparently, Chile has faced difficulties to mature its underlying structure, and to reformulate itself. In the words of former president Aníbal Pinto, Chile’s rather “personality-building” than “sustainability-building” democratic mechanisms, models and styles remain psychologically insecure and fragile in their institutional essence. They have been close to getting defined at the start of any new government, particularly by the current second government of Michelle Bachelet since March 2014. But for one reason or another, endogenous or exogenous, no recent government has been able to materialize a clear and lasting socio-political vision for the nation. In between the problems Bachelet has faced during her current time in office, she has rambled on in the crisis of consensus, adopting a neutral style that has not satisfied her voters, nor the broader public. The political problem connected with all this is that in the view of Chilean voters, the outcome of Bachelet’s second tenure is a type of half-failed state, since in practice institutions operate and there is a democratic order, but there is also a widespread sense of lack of a socially shared national vision and identity. That could lead to another change of course–not by conviction, but by annoyance and habit.

The 2017 Elections: Another Step In The Turbulent Story Of Chile’s Democratic Adolescence

Overall, the disappointment of Chilean voters about Bachelet’s second tenure shortly before the November 2017 elections is not unusual, but rather a normality in the nation’s young democratic history. Yet the fact that the recent branding “adolescent nation” became viral in the country itself indicates that aspects of Chile’s socio-political culture are perceived to be dissatisfying by a majority of the population and as in need to be revisited. The general and presidential elections of November 19, 2017 will be part of this review. Whether they can be a real turnaround, as many hope once again, remains to be seen. How will the Chilean voters decide about what they–as in the past–conceive not just as a “normal” political choice between left and right, but as the future “identity course” of the nation? Despite the economic success of the past years on the one side, many Chilean intellectuals ask, what a proper democratic identity–including economic, political, social, ethnic, demographic dimensions–could mean for a historically “identity-crippled” nation such as Chile, and how such an identity could be concretely created within a more charismatic, enduring and impactful policy-making. This debate will be continued in the face of the outcome of the elections, and it may be more important than the political result in the long term. Can Chile actively emancipate from its historical limitations, including its deep social and political divisions, and become a fully functional “adult” democracy–thus evolving from a zig-zag course between opposed ideological strips towards a more integrated development? The 2017 elections will provide an indication. Whatever their result may be: they represent another step in the turbulent story of Chile’s democratic adolescence.

By Roland Benedikter, Senior Research Fellow, and Miguel Zlosilo, Extramural Contributor, at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

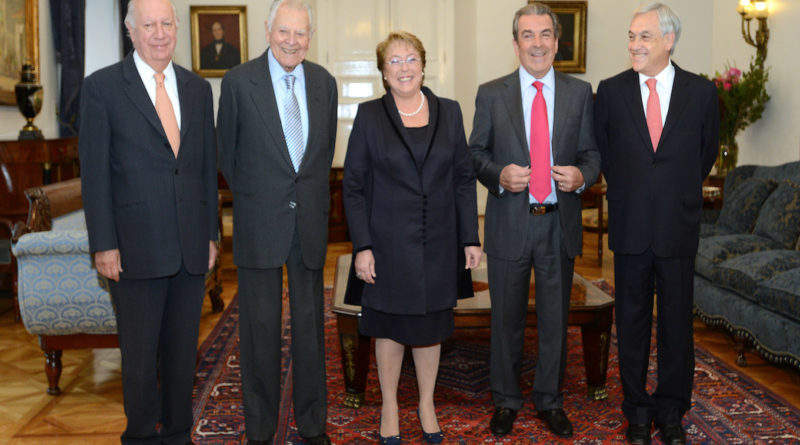

Image: Sebastian Piñera Taken From: Wikimedia