With the TPP Nearing Ratification, U.S. Government Remains Deaf to the Failures of CAFTA-DR

By Jennalee Beazley, Research Associate at the the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF version of this article, click here.

Synopsis:

Any student in an entry level economics class, as well as many liberals, would tell you that free trade, based on the law of comparative advantage, is mutually beneficial to each country’s economy. Many United States presidents and high-ranking U.S. government officials, including Hillary Clinton, have used this notion to rationalize free trade agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994 and The Dominican Republic-Central America-United States Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) in 2005. This year, the Obama Administration is continuing this trend with the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Before jumping on board with the façade of free trade agreement benefits, it is important to examine how past free trade agreements have impacted the developing economies of Latin America. Unfortunately, these agreements have turned out to be tools used to assert U.S. dominance over economically weaker countries by damaging their agriculture sector, taking advantage of cheap labor, and increasing their migration to the United States.

What is CAFTA-DR?

CAFTA-DR was approved by the U.S. Congress on July 27, 2005, and has since established an imbalanced, pro-corporate, trade agreement among the United States, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic.[1] This trading partnership has continued the free trade tenets from the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and has brought some of the same detrimental consequences to its member countries that NAFTA brought to Mexico.[2] Advocates of the agreement– including former President George W. Bush– claimed it would promote stronger trade, investment ties, prosperity, and stability in the region.[3] To achieve these goals, CAFTA-DR mandated reform to laws that protected certain monopolies and implemented protection of Intellectual Property Rights.[4] Additionally, CAFTA-DR prohibits participating countries from enacting new environment protection laws, but does not stop countries from waiving existing laws to encourage investment, even if this change is in violation of international regulations.[5] All together, these provisions provided Central America with a legal framework that favors foreign trade and investment over protecting and prioritizing domestic companies.[6] In other words, rather than a fair free trade agreement, CAFTA-DR created an unfair commercial agreement to advance U.S. interests which materialized through investment into low wage labor sectors such as manufacturing industries, like the famous maquiladoras. As with NAFTA, this framework proved to be damaging to the developing economies of the Dominican Republic and of the Central American countries. (To read more about the impacts of NAFTA please refer to COHA’s article “The North American Free Trade Agreement: A Qualified Failure For Mexico,” or the Center for Economic Policy and Research’s “Did NAFTA Help Mexico? An Assessment After 20 Years.”)[7][8]

During the Washington panel arranged by the Americas Society and Council of the Americas in December 2015, the World Bank Senior Director of Trade and Competitiveness and former Minister of Foreign Trade to Costa Rica, Anabel González, trumpeted the apparent success of CAFTA-DR She noted, “the results have been quite impressive in terms of mobile penetration and the reduction in prices for (telecommunication) services– not only for consumers but also for foreign investors who require these types of services. Overall, the story has been a very positive one,” while she advocates that, “countries like Costa Rica and Panama should also be members of TPP.”[9][10] However, she failed to discuss the imbalanced shift in trade, the displacement of thousands of family farmers, and the manufacturing industry shortcomings. She also failed to mention that due to this “positive story,” one million people from these three countries have left their homes since 2010 in search of better living conditions in the United States and Mexico; many of these migrants are children who contribute to the unaccompanied migrant crisis currently occurring at U.S. borders.[11] This article will assess these economic repercussions on the region and what this could mean for the future of free trade.

Foreign investment

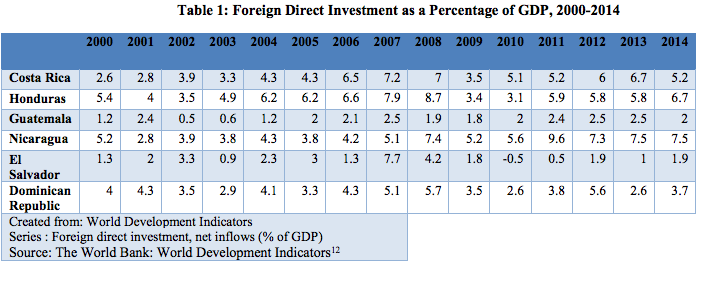

CAFTA-DR undoubtedly let foreign investment flow into the member countries, especially Costa Rica and Honduras, which has created a net job increase and lowered consumer costs. Table 1 shows the growth of foreign direct investment as a percent of GDP in Central America and the Dominican Republic.

Take Honduras for example: after former Secretary of State, Hilary Clinton, played a deciding role in the prevention of former President Manuel Zelaya of returning to office in 2009, there has been a push to embrace CAFTA-DR’s foreign investment provisions.[13] In fact in 2011, the Honduran government hosted an economic conference called “Honduras is Open for Business” and advocated for “charter cities,” which are meant to be economic zones governed by foreign governments or multinational companies.[14][15] OFRANEH, a Honduran minority rights organization, stated “a small group of elite businessmen and politicians are trying to auction off parts of the country to foreign capital in order to create islands of affluence surrounded by a sea of poverty and violence,” in reference to charter cities and increased foreign investment.[16] The Human Rights Watch specifically cites Palm Oil and food companies as instigating violence in land battles, resulting in more than 90 murders this past year.[17] This proves CAFTA-DR is a rigged pro-corporate agreement that only benefits large multinational companies, and drives out the smaller, local industries within the region.

Shift in Trade: Dislocating Family Farmers

Perhaps the most drastic impact of CAFTA-DR has been the shift in trade patterns. Prior to CAFTA-DR the United States was operating a trade deficit with the member countries, meaning the U.S. imported more products from these countries than the U.S. exported to them.[18] Under this agreement, the U.S. is now operating at a trade surplus, exporting more than importing.[19] While this does not account for a large proportion of the United State’s massive economy, it has had a harmful impact on the livelihoods of citizens in the Dominican Republic and Central American countries.

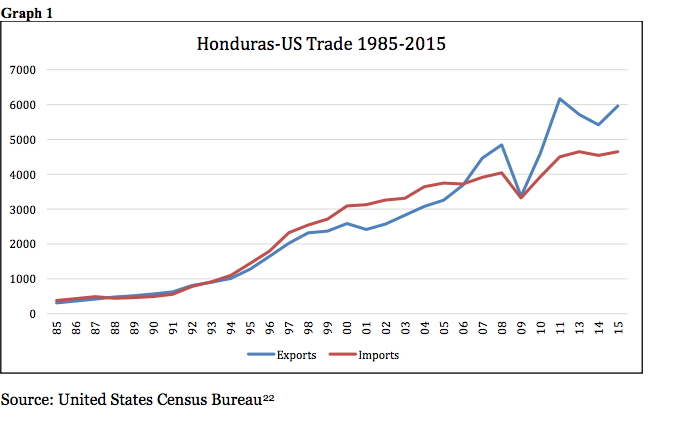

The most notable shift has occurred in Honduras, which went from being a net exporter to a net importer as a result of CAFTA-DR.[20] Honduras fully implemented the clauses of the agreement, at which point Honduras was operating with a 30.4 million USD trade surplus with the U.S. In 2007, only one year later, Honduras operated with a trade deficit of 549.3 million USD.[21] Graph 1 demonstrates how Honduras trade with the United States has drastically shifted under CAFTA-DR. Original data lists exports and imports from the U.S. perspective; however, the Graph 1 presents the trade balance from the Honduras perspective.

Source: United States Census Bureau[22]

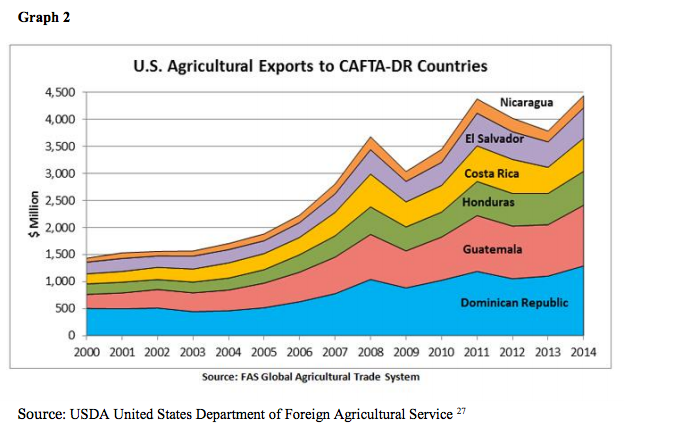

Most of the goods exported to these countries consisted of agriculture goods, such as grains, which impacts on the domestic agriculture industry within these developing countries. During CAFTA-DR discussions, the Bush Administration ignored warnings from Oxfam that 5.5 million central Americans depended on agriculture for their livelihood (1.5 million depended on the rice industry alone).[23][24] Additionally, U.S.-Latino organizations such as the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) and the Labor Council for Latin American Advancement (LCLAA), opposed CAFTA-DR during its creation because of its devastating impact on the agribusiness of these countries; the shift in agricultural trade indicates that their fears have been realized.[25] U.S. farmers are privileged with government financial help (subsidies), advanced technologies, and genetically modified organisms (GMOs), which all contribute to larger farms and exponentially more food at a lower cost. With that said, it is impossible for small family farmers in Central America to compete with the U.S. agriculture industry. As a result of this unfair agriculture competition, United Sates agricultural exports to Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador have increased by 78 percent since CAFTA-DR was passed.[26] Graph 2 demonstrates how agriculture exports from the United States to the member countries has dramatically increased since CAFTA-DR’s implementation.

Source: USDA United States Department of Agriculture: Foreign Agricultural Service [27]

In addition to unfair competition, the agriculture industry from domestic family farmers, United States food imports could be harmful to the future of food security in these countries. Not only does the well-being of the economy rest in the hands of the United States, but so does the populations’ access to food.

Job Creation

Foreign investment and the relocation of multinational companies into the Dominican Republic and Central American countries have displaced families working in rural areas, however, they have also created many jobs in factories, or maquilas. Though these industries mostly assemble clothing, some also assemble imported parts in order to (re-)export them to the United States.[28]

Multinational companies often take advantage of the low costs of production and, conveniently, the low wage labor.[29] Rather than protecting human rights, under CAFTA-DR the United States has only protected laws maintaining low costs of production. In fact, the former U.S. ambassador to El Salvador, Mari Carmen Aponte, has been accused of pushing pro-corporate laws by “threatening to cut [U.S.] development aid to the country.”[30] Moreover, these multinational companies will probably move when a lower cost option presents itself. For example, the TPP may persuade many of these companies to move to Vietnam where the cost of labor is about 52 cents USD an hour, in comparison to the average cost of labor which is around 1.33-1.54 USD per hour in Honduras.[31],[32] While Mexico claims to have an even lower labor cost, the reality is multinational companies are not loyal to any country and these free trade agreements enable them to exploit workers for foreign profit.[33]

Some of these effects can already be seen since apparel imports from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador were lower last year than the year before CAFTA-DR was passed.[34] This is reminiscent of how the maquila industry grew so rapidly in the early years of NAFTA, but a crisis between 2001 and 2003 led to massive layoffs.[35] Similar to the food security problem, this trend could be detrimental to these developing countries since such a large proportion of their economy has become dependent on these multinational companies. In other words, CAFTA-DR has crippled the Dominican Republic and Central American economies by making them reliant on the United States’ economy.

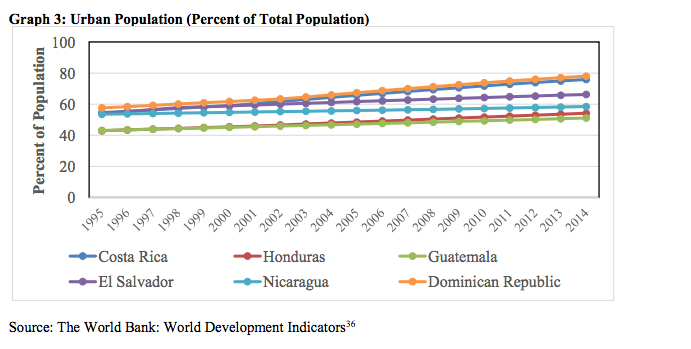

One of the consequences of the weakening of the agricultural sectors and the creation of jobs in maquilas is the dramatic increase in urban population. This movement can be seen in Graph 3: when CAFTA-DR was implemented, there was a sharp increase in the the rate of growth of urbanization in all the member countries.

Source: The World Bank: World Development Indicators[36]

Another harmful effect of foreign investment, encouraged by CAFTA-DR, is its dramatic impact on the environment. Manuel Pérez-Rocha, an associate fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies, discussed how mining has taken over 14 percent of territory in Central America as a result of the foreign investment law reforms from CAFTA-DR, at the congressional briefing in December 2015.[37] Not only did Mr. Pérez-Rocha talk about how mining for foreign profit is destroying a large amount of land in these countries, he also pointed out how CAFTA-DR was used as evidence to sue El Salvador and Costa Rica for their environment protection regulations that have limited the amount of foreign mining permitted.[38]

Poverty and inequality

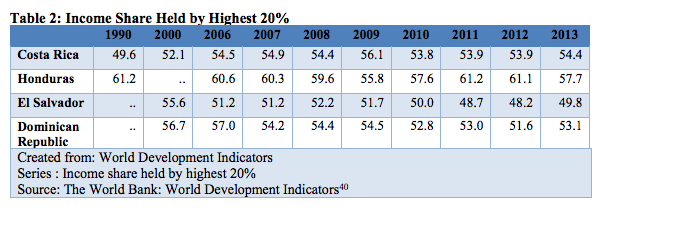

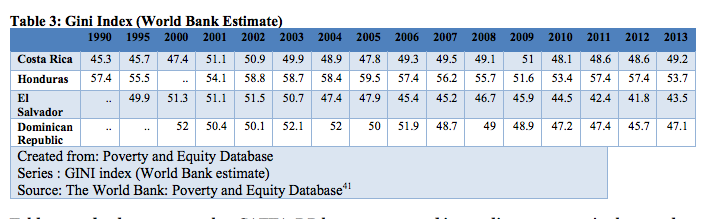

The boom of investment that took place in these countries enriched a domestic minority. While poverty rates have been slowly declining in Latin America, inequality has continued to plague these countries.[39] Investments through the free trade agreement were supposed to encourage domestic business to decrease economic disparity, reduce poverty, and inequality; however, it has mostly favored wealthy locals. As shown in Table 2, 20 percent of the population still accounts for half of the income in these countries. Table 3 demonstrates the lack of change in the Gini index for the member countries; this indicates there has been no change in income distribution since the introduction of CAFTA-DR (Data not available for Nicaragua and Guatemala).

Source: The World Bank: World Development Indicators[40]

Source: The World Bank: Poverty and Equity Database[41]

Tables 2 and 3 demonstrate that CAFTA-DR has not assuaged inequality or poverty in the member countries.

Drugs, Violence, and Forced Migration

The rising levels of inequality, especially regarding the destruction of subsistence agriculture, are extremely important to understand the economic consequences of CAFTA-DR. It has exacerbated many of the immigration and drug trafficking problems that the U.S. faces today. While political corruption and civil wars are also key components in these regional problems, CAFTA-DR has certainly contributed to economic disparity. Without an increase in economic opportunities, more and more people look to establish their livelihoods through drug trafficking, gang violence, or emigration northward.[42] The American Immigration Council cites high levels of crime and violence for pushing people to migrate out of their home country.[43] More and more families and children have made the choice to risk their lives on the journey to the United States in pursuit of a better life in recent years; 63,000 unaccompanied children, mostly from Central America, have come to the southern border of the United States seeking better opportunities than the ones offered in their home countries.[44] The U.S. presidential election has focused a great deal on reforming immigration policy to keep further undocumented people out and to reduce drug trafficking; however, this only focuses on the symptoms of an economic disease facing Central America known as Free Trade.

The future of CAFTA-DR and Free Trade

By evaluating CAFTA-DR nearly 11 years later, it is clear that this agreement has not only failed to bring economic prosperity to the region, but has also opened the doors to foreign investment with little or no protection for Central American land, resources, workers, further fueling internal displacement, violence, and migration. Rather than establishing free trade for mutual benefit, CAFTA-DR implemented an imbalanced commercial agreement that favored US corporate interests.

Some member countries have taken steps to improve their own situation in regards to CAFTA-DR. For example, earlier in May, the presidential candidates for the Dominican Republic, including recently victorious incumbent Guillermo Moreno, agreed the stipulations of CAFTA-DR need to be revised. In an interview with the Dominican Republic magazine, Hoy, the men discussed this proposed revision by working with La Confederación Nacional de Productores Agropecuarios (The National Confederation of Agricultural Producers) in order to create laws protecting the production of rice, beans, meat, garlic, onion, sugar, coffee, and other food products.[45]

It is clear that international leaders are also taking note of issues surrounding free trade in developing countries. Researchers for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) acknowledged the economic downfalls of liberalized trade stating that “The IMF also recognizes that full capital flow liberalization is not always an appropriate end-goal, and that further liberalization is more beneficial and less risky if countries have reached certain thresholds of financial and institutional development.”[46] This statement highlights that policy advisors need to take into account the fact that disproportionate productivity can have negative impacts on lower-income countries.

Although World Bank Senior Director of Trade and Competitiveness, Annabel González, claims that an eventual membership in the TPP would be good for Costa Rica’s economy, the reality is that the TPP could likely result in deeper economic disparity and worker exploitation.[47] The fact is, the TPP, like CAFTA-DR, could hurt developing economies because it could allow the United States to take advantage of low production costs while dumping subsidized agriculture goods into these countries. As IMF researchers have said, “Policymakers, and institutions like the IMF that advise them, must be guided not by faith, but by evidence of what has worked.” [48] The United States government must consider the failures of CAFTA-DR while moving forward with free trade.

By Jennalee Beazley, Research Associate at the the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and instituional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to LatinNews. com and Rights Action.

Featured Photo: by Yamil Gonzalez. Taken from Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/people/38727033@N05

[1] “Public Citizen, Inc. and Public Citizen Foundation.” Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA). Accessed May 18, 2016. http://www.citizen.org/Page.aspx?pid=1046.

[2] “CAFTA-DR (Dominican Republic-Central America FTA) | United States Trade Representative.” The Office of the United States Trade Representative. Accessed May 17, 2016. https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/cafta-dr-dominican-republic-central-america-fta.

[3] “Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA).” U.S. Department of State Archive. Accessed May 18, 2016. http://2001-2009.state.gov/p/wha/rt/cafta/.

[4] Ibid

[5] James, Deborah. “Free Trade and the Environment.” Global Exchange. Accessed May 31, 2016. http://www.globalexchange.org/resources/wto/environment.

[6] “CAFTA-DR (Dominican Republic-Central America FTA) | United States Trade Representative.” The Office of the United States Trade Representative. Accessed May 17, 2016.

[7] Doleac, Clément. “The North American Free Trade Agreement: A Qualified Failure For Mexico.” Council on Hemispheric Affairs. April 09, 2015. Accessed May 31, 2016. https://coha.org/the-north-american-free-trade-agreement-a-qualified-failure-for-mexico/.

[8] Weisbrot, Mark, Stephan Lefebvre,, and Joseph Sammut*. “Did NAFTA Help Mexico? An Assessment After 20 Years.” Center for Economic Policy and Research. January 2014. Accessed May 31, 2016. http://cepr.net/documents/nafta-20-years-2014-02.pdf.

[9] Luxner, Larry. “Ex-trade Minister Anabel González: TPP, like CAFTA, Will Help Costa Rica in Long Run -.” The Tico Times. December 14, 2015. Accessed May 18, 2016. http://www.ticotimes.net/2015/12/14/ex-trade-minister-anabel-gonzalez-tpp-like-cafta-will-help-costa-rica-in-long-run.

[10] “Americas Society and Council of the Americas | AS/COA.” Americas Society and Council of the Americas | AS/COA. Accessed May 18, 2016. http://www.as-coa.org/.

[11] Rietig, Victoria, and Rodrigo Dominguez Villegas. “Migrants Deported from the United States and Mexico to the Northern Triangle: A Statistical and Socioeconomic Profile.” Migrationpolicy.org. September 2015. Accessed May 18, 2016. http://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/migrants-deported-united-states-and-mexico-northern-triangle-statistical-and-socioeconomic.

[12] “World Development Indicators| World DataBank.” World DataBank. Accessed May 31, 2016. http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=2.

[13] “Attempted Coup and Misguided U.S. Sanctions in Venezuela.” COHA. March 12, 2015. Accessed May 23, 2016. https://coha.org/attempted-coup-and-misguided-u-s-sanctions-in-venezuela/#comments.

[14] Ibid

[15] “Honduras Is Open for Business.” COHA. July 26, 2011. Accessed May 23, 2016. https://coha.org/honduras-is-open-for-business/.

[16] “US Activists Protest Charter Cities: An ‘Assault on Honduran Sovereignty'” TeleSUR. June 6, 2015. Accessed May 23, 2016. http://www.telesurtv.net/english/analysis/US-Activists-Protest-Charter-Cities-An-Assault-on-Honduran-Sovereignty-20150606-0011.html.

[17] “World Report 2015: Honduras.” Human Rights Watch. 2015. Accessed May 23, 2016. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2015/country-chapters/honduras.

[18] “Global Agriculture Trade System.” United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service. Accessed May 18, 2016. http://apps.fas.usda.gov/GATS/default.aspx.

[19] Ibid

[20] “Failed Trade Policy & Immigration: Cause & Effect.” Public Citizen. July 2015. Accessed May 17, 2016. https://www.citizen.org/documents/failed-trade-policy-and-immigration.pdf.

[21] “Foreign Trade: U.S. Trade in Goods with Honduras.” United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 20, 2016. https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c2150.html#2004.

[22] Ibid

[23] “CAFTA by the Numbers: What Everyone Needs to Know.” Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch. July 2004. Accessed May 23, 2016. https://www.citizen.org/documents/CAFTAbyNumbers.pdf.

[24] “A Raw Deal for Rice under CAFTA-DR How the Free Trade Agreement Threatens the Livelihoods of Central American Farmers.” Oxfam Briefing Paper. November 2004. Accessed May 20, 2016. http://www.oxfamamerica.org/static/media/files/a-raw-deal-for-rice-under-CAFTA-DR.pdf.

[25] “Failed Trade Policy & Immigration: Cause & Effect.” Public Citizen. July 2015. Accessed May 17, 2016. https://www.citizen.org/documents/failed-trade-policy-and-immigration.pdf.

[26] Perla, Héctor, Jr. “The Impact of CAFTA: Drugs, Gangs, and Immigration.” TeleSUR. March 1, 2016. Accessed May 18, 2016. http://www.telesurtv.net/english/opinion/The-Impact-of-CAFTA-Drugs-Gangs-and-Immigration-20160301-0008.html.

[27] “Central America and the Caribbean: Prospects for U.S. Agricultural Exports.” USDA United States Department of Agriculture: Foreign Agricultural Service. March 30, 2015. Accessed May 23, 2016. http://www.fas.usda.gov/data/central-america-and-caribbean-prospects-us-agricultural-exports.

[28] Beachy, Ben. “Economic Underpinnings Of Migration In The Americas.” Congress Woman Mary Kaptur. September 2014. Accessed May 17, 2016. http://www.kaptur.house.gov/images/pdf/ben_beachy__cafta_and_the_forced_migration_crisis.pdf.

[29] Ibid

[30] “CISPES Statement on New US Ambassador to El Salvador.” CISPES: Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador. April 13, 2016. Accessed May 20, 2016. http://cispes.org/article/cispes-statement-new-us-ambassador-el-salvador.

[31] “World Wide Minimum Wages: China, India, Indonesia, Africa, The Netherlands, Latin Amercia.” WageIndicator.org. Accessed May 18, 2016. http://www.wageindicator.org/main/salary/minimum-wage.

[32] Beachy, Ben. “Economic Underpinnings Of Migration In The Americas.” Congress Woman Mary Kaptur. September 2014. Accessed May 17, 2016. http://www.kaptur.house.gov/images/pdf/ben_beachy__cafta_and_the_forced_migration_crisis.pdf.

[33] “Understanding the Central American Refugee Crisis: Why They Are Fleeing.” Immigration Policy Center. May 17, 2016. Accessed May 27, 2016. http://www.immigrationpolicy.org/special-reports/understanding-central-american-refugee-crisis-why-they-are-fleeing.

[34] Ibid

[35] Doleac, Clément. “The North American Free Trade Agreement: A Qualified Failure For Mexico.” COHA. April 09, 2015. Accessed May 27, 2016. https://coha.org/the-north-american-free-trade-agreement-a-qualified-failure-for-mexico/.

[36] “World Development Indicators| World DataBank.” The World Bank. Accessed May 27, 2016. http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=2.

[37] Pérez-Rocha, Manuel. “Environmental Destruction from Mining in Central America and Investment Protections under the CAFTA-DR: Economic Underpinnings Of Migration In The Americas.” Congress Woman Mary Kaptur. December 2015. Accessed May 17, 2016. http://www.kaptur.house.gov/images/pdf/cafta_briefing_mpr_presentation.pdf.

[38] Ibid

[39] “Social Panorama of Latin America • 2015.” Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. 2015. http://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/39964/S1600226_en.pdf?sequence=1.

[40] “World Development Indicators| World DataBank.” The World Bank. Accessed May 27, 2016. http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=2&country=&series=SI.DST.05TH.20&period=#

[41] “Poverty and Equity Database.” World DataBank. Accessed May 31, 2016. http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=poverty-and-equity-database#.

[42] Perla, Héctor, Jr. “The Impact of CAFTA: Drugs, Gangs, and Immigration.” TeleSUR. March 1, 2016. Accessed May 18, 2016. http://www.telesurtv.net/english/opinion/The-Impact-of-CAFTA-Drugs-Gangs-and-Immigration-20160301-0008.html.

[43]“Understanding the Central American Refugee Crisis: Why They Are Fleeing.” Immigration Policy Center. May 17, 2016. Accessed May 27, 2016. http://www.immigrationpolicy.org/special-reports/understanding-central-american-refugee-crisis-why-they-are-fleeing.

[44] Kaptur, Mary. “Economic Underpinnings Of Migration In The Americas.” The Online Office of Congresswoman Marcy Kaptur. September 2014. Accessed May 17, 2016. http://www.kaptur.house.gov/index.php?option=com_content.

[45] Rubens, Evaristo. “Moreno Y Pelegrín Coinciden En Que Hay Que Revisar CAFTA-DR En Próximos 4 Años.” Hoy. May 12, 2016. Accessed May 18, 2016. http://hoy.com.do/moreno-y-pelegrin-coinciden-en-que-hay-que-revisar-CAFTA-DR-en-proximos-4-anos/.

[46] Ostry, Jonathan D., Prakash Loungani, and Davide Furceri. “Neoliberalism: Oversold? — Finance & Development.” The International Monetary Fund. June 2016. Accessed May 31, 2016. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2016/06/ostry.htm.

[47] Luxner, Larry. “Ex-trade Minister Anabel González: TPP, like CAFTA, Will Help Costa Rica in Long Run -.” The Tico Times. December 14, 2015. Accessed May 18, 2016. http://www.ticotimes.net/2015/12/14/ex-trade-minister-anabel-gonzalez-tpp-like-cafta-will-help-costa-rica-in-long-run.

[48] Ostry, Jonathan D., Prakash Loungani, and Davide Furceri. “Neoliberalism: Oversold? — Finance & Development.” The International Monetary Fund. June 2016. Accessed May 31, 2016. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2016/06/ostry.htm.