War in Peace: Exploring the Roots of El Salvador’s Gang Violence

By Jessica Farber, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF version of this article, click here.

Nearly two and a half decades have passed since the end of a devastating twelve-year civil war in El Salvador between leftist guerilla forces and a United States-funded right-wing military government. By the end of this conflict, over 75,000 civilians had been killed and at least one million displaced. Yet the so-called “post-war” El Salvador has been far from peaceful.[1]

In the wake of the war, a massive gang crisis erupted in which two rival gangs, La Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18 (18th Street gang), have unleashed violence and asserted their dominance over more than half of the territory in El Salvador.[2] At the same time, they have carried out a seemingly senseless protracted conflict against each other and those caught up in a web of extortions, drug trafficking, and an atmosphere of kidnapping and common crimes. After a failed truce in 2014, the situation in the country worsened considerably. As the homicide rate approached one murder per hour by June 2015, El Salvador, a tiny nation of 6.3 million, earned the sobriquet of the most dangerous country in the world outside of a war zone.[3] Both in and outside of the country, fear has soared. Foreign newspaper articles constantly detail the latest increase in the homicide rate, and the Obama administration has called the MS-13 an “international criminal organization,” urging travelers to avoid the region.[4]

The effects of the gang wars on Salvadoran society cannot be overstated. Every day, innocent bus drivers, tortilla sellers, and other small business owners are murdered when they cannot pay la renta (the extortion fee) to the gangs. The Economist estimates that Salvadorans pay around $756 million in extortion fees, or about three percent of the country’s GDP, to the gangs every year.[5] While the wealthy can hide behind luxury compounds in the hills of the capital, the poor continue to pay the ultimate price of the gang violence: loss of education, income, productivity, and the right to move about freely.

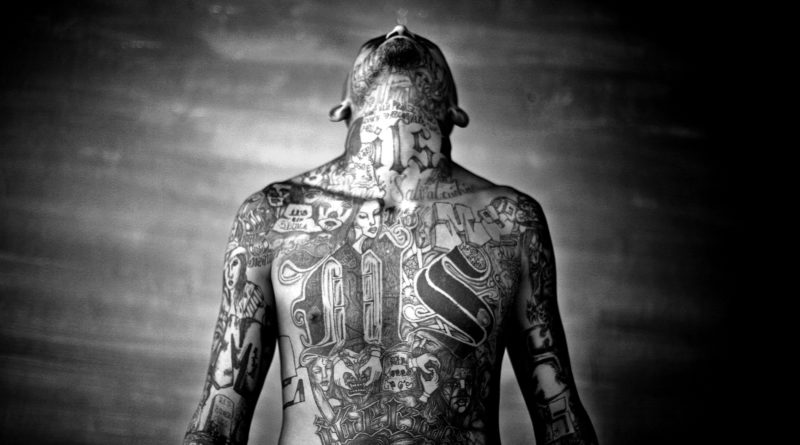

Yet the violence that has embroiled the country is more nuanced than a straightforward clash between rival gangs. A variety of complex and intertwining factors, including the social exclusion of gang members, a series of poorly targeted policies in the immediate postwar period, and widespread poverty and inequality have contributed to the violence that continues to plague the country today. Though recent policies have been more mindful of the many facets of the conflict, the overall demonization of gangs by both U.S. and Salvadoran governments has served more to exacerbate violence and fear in El Salvador than to quell the ongoing bloodshed. By exploring the complex relationships between gangs and the government, this article will illuminate the human experience of gang members underlying the tattooed faces and rhetoric of terror, realities that the heavy-handed Salvadoran policy backed substantially by the United States has largely ignored.

From Neighborhood Gangs to Transnational Maras

Understanding the severity of the current gang crisis is impossible without first considering the contextual evolution of the gangs.[6] Gang activity in El Salvador can be traced back to the 1960s, which followed a period of increased industrialization and urbanization. During the height of the war in the late 1980s and early 1990s, several small turf-based youth gangs or pandillas with little connection to one another formed in different barrios in San Salvador. They carried out small crimes and low-scale violence, mostly against members of other gangs, and acted as neighborhood watchdogs. In these early years, the gangs had little control over the city because they occupied only small territories and were not affiliated with each other.[7]

At the same time, new Latino gangs were emerging within the United States as Central American refugees began arriving in waves. In the late 1970s and 1980s, two rival gangs, La Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio 18, formed in Los Angeles, one of the most popular destinations for Latino immigrants at the time. These gangs originated largely as Latino self-defense groups defending Latino neighborhoods against other ethnic youth gangs, such as Korean and Cambodian immigrant gangs.[8] Barrio 18 was originally formed by Mexican immigrants, though it quickly accepted other Latinos, especially Salvadoran and Guatemalan immigrants who arrived in large numbers during their respective wars.[9] A second influx of Salvadoran refugees formed the rival group, Mara Salvatrucha, in the late 1980s.[10]

After funneling roughly $6 billion USD to the Salvadoran military authoritarian regime responsible for killing and disappearing tens of thousands of civilians, the U.S. government then helped transport gang violence back to El Salvador. In 1996, the U.S. Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Illegal Immigrant Responsibility Act, which repatriated anyone sentenced to at least one year in prison or anyone caught without the requisite documents.[11] The vague terminology in the law allowed even the most minor offenses, such as speeding or shoplifting, to be deemed major felonies. In the span of just three years, the U.S. government forcibly repatriated over 150,000 Salvadorans, adding to an influx of nearly 400,000 more who willingly returned just after the end of the war.[12] In essence, the United States succeeded in partially ameliorating its own gang problem by exporting the violence to a country wholly unequipped to handle such a crisis.

In El Salvador, convicted youth arrived in a country of origin they barely knew, one ravaged by the traumas of war. Due to weak institutions and lax law enforcement, gang members were able to reproduce the same behavior patterns that had allowed them to survive in the contentious and multi-ethnic environment of Los Angeles.[13] As gang members returned and formed local chapters of MS-13 and Barrio 18, they brought with them the symbols, language, and tattoos of the L.A. street gangs. Unlike in Los Angeles, however, where membership was defined by identity and ethnicity, the line defining gang membership in the ethnically homogenous El Salvador was blurred. In the absence of an obvious ethnic affiliation, gang members showed allegiance to their respective gangs, and attempted to create what José Cruz, Salvadoran gang expert and director of the Latin American and Caribbean Center at Florida International University, terms a “collective identity” by carrying out acts of violence and tattooing their bodies.[14] With little hope for survival otherwise, all of the previously unaffiliated turf-based gangs quickly aligned with one of the two rival maras (gangs with transnational ties).

In the mid-1990s, Salvadoran government leaders focused on recovering from postwar devastation and implementing the Structural Adjustment Policies of the Washington Consensus in order to receive foreign aid and failed to establish programs to quell gang violence or to re-integrate deported Salvadorans.[15] This inattention combined with the widespread availability of firearms in the wake of the civil war allowed social cohesion in the respective gangs to deepen and the gang crisis to escalate.

Stoking the Fire: Heavy-Handed Policy Ushers in a New Era of Violence

The definitive moment when gangs were pushed to become the institutionalized, extortion-racketing groups that they are today, occurred in 2003. That year, El Salvador’s governing right-wing National Republican Alliance Party (ARENA) implemented a repressive crackdown policy called Mano Dura (Iron Fist). Mo Hume, an ethnographic researcher from the University of Glasgow, has argued that the policy was an attempt by the party to portray youth gangs “as a common enemy of good citizens” to garner support for the 2004 elections.[16] This policy gave the police and the military complete authority to arrest anyone they suspected of gang involvement, without allowing them to have a fair trial.[17] Arrests could be made arbitrarily of children as young as twelve with as little evidence as simply the presence of tattoos, the display of hand signals or dress.[18]

In an effort to further control gang violence, Mano Dura was upgraded to Super Mano Dura in 2004, a measure that inadvertently allowed the gangs to become more organized and less amateur.[19] The mass incarceration that resulted flooded an already shaky prison system with gang members and brought together gangsters from around the country and abroad, allowing the gangs to re-organize and strengthen their national and international networks.[20] Because the police separated prisoners by gang, jails became central nodes of control for each gang, allowing leaders to coordinate the smuggling of arms and attacks on rival gangs with ease.

Furthermore, Mano Dura facilitated human rights abuses against arrested gang members by police and led to the emergence of non-state armed “social cleansing” groups, or “death squads,” that killed anyone suspected of being in a gang.[21] In the face of such virulent repression, the gangs sought to wage war against the state. To attain the resources necessary to do so, the gangs created links to drug-trafficking cartels inside prisons and established extortion rackets, which imposed “security taxes” on businesses in the areas they controlled.[22] Mo Hume argues that the heavy-handed repression of Mano Dura indicates a “severe impediment in the already fragile democratic project in El Salvador and highlights the historical tendency to rely on repressive governance.”[23]

The United States also played a role in supporting this security agenda. In addition to providing funding to Salvadoran paramilitary forces, special task forces were set up in the United States to eliminate gangs, specifically by targeting members of MS-13 in Los Angeles.[24] The policy undeniably contributed to the culture of fear and demonization of the gang members, which, as Hume maintains, was central to legitimizing the ARENA party’s use of heavy-handed tactics.[25] At the same time, such aggressive crackdowns played into the public’s fear of terrorism in the United States, which helped to garner support for conservative immigration policy.

A Search for Belonging

While the bitter rivalry between the gangs continues to cost thousands of innocent Salvadorans their lives, the repressive policies of Mano Dura in El Salvador and zero-tolerance policing in the United States have failed to address some of the root causes of the violence and do not reflect an understanding of the factors that might influence individuals to join gangs. A confluence of high levels of inequality and poverty, few economic prospects, and social exclusion has created an environment ripe for gang membership and enables members to establish an identity in a fragmented society. When young Salvadoran offenders or gang members who grew up in the United States (many of them permanent residents) were deported, they arrived with no family support in an unfamiliar country struggling to rebuild itself after the war. Excluded by both nations, they felt neither Salvadoran nor American. José Cruz conducted a survey of 1,000 youth gang members in San Salvador and found that through gang membership, the majority of the youth sought mutual respect, identity, friendship, and a replacement family.[26]

Perhaps most significant is the fact that many gang members have grown up surrounded by a culture of violence, whether in El Salvador or in Los Angeles. Some were child combatants on either side of the civil war, and many witnessed politically motivated executions of friends and family members. In Los Angeles, youth gang members often grew up in broken families in ethnically fragmented communities, neglected by immigrant parents working two or more jobs and turned to gangs to survive.[27] The common bond of “suffering” has united them.

Joining a gang also provides an opportunity for excluded youth to gain economic advantages in a society where employment prospects are low, especially for those already marked as gang members by tattoos.[28] Aside from menial positions held by new members, such as lookouts, the gangs need accountants, lawyers, and doctors in order to ensure their operations.[29] In the face of the consistent violation of their rights, marginalization from society and the lack of any conceivable alternative opportunities, many youth have turned to gang membership as the only option for survival.

The media rarely acknowledges such human instincts, nor does it attempt to understand their backgrounds. Instead, journalistic accounts of gang violence tend to depict gang members as heartless, ruthless criminals, feeding into the public’s sense of fear. This fear, in turn, has taken the form of “death squads” and support for Mano Dura, which only intensifies gang members’ sense of exclusion and rejection by society.

The Battle Continues

Since the rise of the former leftist guerilla group Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) to the presidency in 2009 with the election of Mauricio Funes, the government has devoted significant efforts to combatting deeply entrenched corruption and inequality.[30] This break from a long period of hardline right-wing rule by the ARENA party, a loyal ally of the U.S. government, sparked hope for much of the population who longed for the peace, democracy, and political and economic freedoms that failed to materialize at the end of the civil war.[31] Sure enough, the FMLN proved its commitment to social progress and elevating marginalized groups through a series of sweeping reforms. In 2014, the Social Development and Protection law, presented by Funes in 2013, was approved by the Legislative Assembly, ensuring that administrative projects such as the provision of universal primary and secondary education, free meals to school children, and universal public healthcare would be cemented into law as guaranteed human rights.[32]

Indeed, with the support of the Organization of the American States (OAS) and the United Nations, a truce was brokered in 2012 between MS-13 and Barrio 18 gangs. The truce swiftly led to a 41 percent reduction in homicides in 2013 and a reduction of the daily homicide count from 14 to five.[33] While the FMLN has denied direct involvement in the truce, Funes has admitted to facilitating it, and the rational and humane manner in which the truce was brokered (by a former insurgent turned government advisor and a Catholic bishop) deserves recognition.[34] As the forum for international democratic debate, Open Democracy, describes, the negotiation “contributed to a recognition of the social contours of the gang phenomenon and opened discussions at national and international levels about prevention, reintegration, and rehabilitation.”[35] Furthermore, the truce prompted the creation of “Violence-Free Zones” in eleven municipalities across the country. In a few of these zones, where local authorities and civil society took advantage of the opportunity to deepen re-integration measures, homicide rates continue to be far lower than in other parts of the country. The peace offered an opportunity to establish a bakery and a chicken farm in the first “violence-free zone,” Ilopango, to provide employment for gang members.[36] The creation of these zones, based on agreements between local governments, gangs and facilitators, represented a major first step in a positive direction towards peace in the country.

Despite a decrease in homicides, however, extortion continued and criticism for the truce rose. Disappearances were reported at an alarmingly high rate and the discovery of mass graves in early 2014 revealed that killings had been occurring all along, albeit covertly.[37] Instead, the break in fighting actually served as an opportunity for the gangs to consolidate their hold over their territories of control. Additionally, testimonials from child migrants arriving at the U.S. border have suggested that during the truce, gangs were stepping up their recruitment tactics to target even younger children. [38] With political polarization and decreasing public support for the truce, much of the funding promised by the government for prevention and rehabilitation in the “violence-free zones” never materialized. As authorities began to transfer gang members back to maximum-security prisons, violence soared once more, dashing initial hopes for peace. What might have served as the foundation for widespread peace in El Salvador and an opportunity to institutionalize prevention measures quickly disintegrated with the collapse of the truce only a year after negotiations. José Cruz attributes the breakdown of the truce to “a lack of any follow-up prevention and rehabilitation programs to tackle root causes such as poverty, police brutality, education, and overcrowded prisons.”[39]

In the aftermath of the failed truce, newly elected FMLN president Sánchez Cerén responded to public pressure for a more visible and aggressive approach to gang violence. In a return to the heavy-handed policing reminiscent of the Mano Dura, the president made clear that the government was no longer willing to negotiate with gangs. Cerén sent hoards of masked policemen and National Guard members deep into the slums where the gangs have exercised greatest control. The renewed force with which the government, police, and National Guard have united to crack down on the gangs has led to the deaths of 346 gang members and 16 police officers in violent confrontations from January to June 2016.[40] In response to accusations of increasing extrajudicial killings in the police force, El Salvador’s Human Rights Ombudsman, David Morales, has stated that, “there is serious evidence that government agents have acted outside of the law.”[41] In light of such abuses however, the FMLN has made efforts to bring the perpetrators to justice, as exemplified by the July 12, 2016 arrest of seven police officers involved in the so-called 2015 “San Blas Massacre” in which six alleged gang members and two civilians were killed.[42] The Attorney General confirmed that at least two of the dead had nothing to do with gangs.[43] Aside from mandatory human rights training for PNC and National Guard members, it is critical that the government, in conjunction with police leaders, continues to monitor and reign in abuses in law enforcement bodies in order to realize progress.

While the Cerén administration continues to crack down on the gangs, it has also devised an ambitious new peace plan, Plan El Salvador Seguro, which reflects efforts by the government to understand root causes of the violence. The plan, whose stated aims are a notable improvement from the repressive Mano Dura, is the result of collaboration between the government, civil society, NGOs, and the Catholic Church. Through it, about $1.5 billion USD, or nearly three-quarters of the plan’s budget, has been appropriated for rehabilitation and youth-geared prevention programs.[44]

Where much of the funding for the $2.1 billion USD plan will come from, however, remains unclear, and ARENA leaders in the Legislative Assembly and Supreme Court have thwarted efforts to implement the plan by blocking around $900 million USD meant for social spending, posing a significant obstacle to achieving peace.[45] In early June 2016, a mayor from the ARENA party was arrested on charges of conspiring with gang leaders, allegedly having offered them goods or employment paid for with public money in exchange for votes or promises to decrease killings.[46] Days later, fifteen municipal employees had been charged in connection with the case along with at least 36 gang members.[47] Evidently, the depth of government corruption cannot be underestimated and implementation of the plan will require greater transparency and accountability in the local government and police forces.

Another key challenge for the FMLN government will be controlling the communication flows between imprisoned gang leaders and their members on the outside. Underpaid prison guards have been found to accept bribes of two to three times their wages from gang members in exchange for being allowed to take cell phones into the prisons.[48] From the jail cells, arrested gang leaders are then able to communicate and organize the smuggling of arms with ease. Despite efforts by the government to force telecommunication companies to weaken or block signal strength around prisons, the companies, which are largely ARENA-backed, have been reluctant to comply.[49] “This is a war over modes of communication,” Francisco Pacheco, director of the U.S.-based National Network of Salvadorans in the Exterior (RENASE) expressed in an interview with COHA.

There is no denying that gangs have created an unlivable environment for El Salvador’s civilian population. In 2015 alone, 1,012 youth under the age of 20 were killed in homicides.[50] The situation is urgent and requires direct action immediately. The persistent and extreme violence has resulted in thousands of forced internal displacements and continues to drive migrants in waves to the United States. In addition, internal displacement has broken up families, caused psychological trauma for children, limited parents’ abilities to work, and limited access to the justice system. Arnulfo Franco, the director of the Association for the Communal Cooperation and Development of El Salvador (CORDES) and an ex-guerilla combatant for the FMLN during the war, is now witnessing as the very communities he has helped to re-settle and re-build are once again being torn apart by violence. “This is worse than the war,” he lamented in a recent interview with the author, a sentiment echoed by countless local Salvadorans. Statistically, he is correct. During the war, the homicide rate peaked at 113 conflict deaths per 100,000 people, and today, the rate has surpassed that with 116 people slain for every 100,000, over 17 times the global homicide average.[51] The time to act is now, but this action must move beyond the reliance on brute force to address the deep-rooted and long-term issues at hand.

Light on the Horizon?

At long last, the latest reports have shown that the homicide rate is on the decline—from 611 killings in March 2016 to 333 in June 2016.[52] Yet while government officials will be quick to attribute the decrease in numbers to the success of greater crackdowns, the international community should be cautious about declaring an end to the crisis. Although the sudden decrease in violence may be due in part to government tactics, increasing evidence is showing that the drop in homicides may also be due to increasing cooperation among opposing gang leaders. On July 5, 2016, El Salvador’s online newspaper, El Faro, reported that leaders of the three main groups (MS-13 and two factions of Barrio 18) have agreed to a non-aggression pact wherein the gangs will respect each other’s territories without mediators, in an effort to wage a “joint political war against the government.”[53] By doing so, the gangs are pressuring the government to return to negotiations and a strategy based on dialogue. Since the government has given no indication that it will back down on the crackdowns any time soon, it could be only a matter of time before the violence resumes. On July 9, 2016, the PNC confirmed that members of MS-13 had shot and killed the FMLN mayor of the municipality of Tépitan.[54] This assassination comes just months after an ARENA mayor was killed by gang members in April 2016.[55]

As for Washington’s diplomatic aims, it appears that little has changed in terms of the typical pattern of relations with Central American governments that has become so ingrained in U.S. foreign policy: providing financial support to weak institutions and increasing spending on deportations. While the government and gangs continue to battle for power in El Salvador, the United States has maintained a muddled position. This past winter, the Obama Administration deemed El Salvador “too dangerous” for Peace Corps operations, yet continued to deport Salvadoran women and children despite threats to their lives.[56] The 2015 Alliance for Prosperity Plan’s continued focus on greater militarization in the region similarly raises doubts as to the reliance on violence to prevent violence in El Salvador. Francisco Pacheco stressed that it is essential that the United States invest in social capital over simply funding for more arms. “The U.S. always wants to help, but it often just makes matters more complicated,” Pacheco reasoned. “If we want to see any real change, the U.S. must condition its aid.” In that light, it is imperative for the U.S. government to divert energy to ensuring accountability and transparency in Salvadoran institutions, or else there can be little hope for the effective implementation of any plan that addresses the true causes of gang violence.

Conclusion

As long as the Salvadoran government continues to rely on repressive security measures without long-term investment in prevention and re-integration programs, the likelihood of a peaceful future in El Salvador will remain uncertain. Of course, the unlivable environment that gangs have created in the country is inexcusable and the violence they carry out on a daily basis is horrific. Despite this, and indeed because of it, it is crucial for both the Salvadoran and U.S. governments to consider the external factors that have influenced the progression of gang violence. While the use of force in the short term is inevitable to stem the violence that is forcing thousands of Salvadorans to seek asylum in the United States, this force must be accompanied by policies that specifically target the deep-rooted structural inequalities that, unabated, will continue to drive countless youth to join gangs. Both Plan El Salvador Seguro and the Alliance for Prosperity represent well-intentioned first steps towards progress along these lines. With continued oversight to ensure that funds are spent appropriately and sustainably, leaders in both the United States and El Salvador can work toward a solution that does not rest solely on fighting violence with violence. Rather, they can craft a solution that is founded on education, social progress, and respect for human rights.

By Jessica Farber, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Original research on Latin America by COHA. Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and instituional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to LatinNews. com and Rights Action.

Featured Photo: Tattoo of a gang member. Taken from Flickr.

[1] Moodie, Ellen. El Salvador in the Aftermath of Peace: Crime, Uncertainty, and the Transition to Democracy (Philadelphia: 2011) 1.

[2] “Los Municipios Más Violentos en 2015.” La Prensa Gráfica. March 2016. Accessed 18 July 2016.

[3]Jonathan Watts. “One murder every hour: how El Salvador became the homicide capital of the world.” The Guardian, 22 August 2015. Accessed 18 July 2016.

[4] Cabezas, José. “U.S. government targets infamous street gang MS-13,” The World Affairs Journal, 5 June 2013. Accessed 18 July 2016.

[5] “The Gangs that Cost 16% of GDP,” The Economist, 21 May 2016. Accessed 18 July 2016. http://www.economist.com/news/americas/21699175-countrys-gangs-specialise-extortion-they-may-be-branching-out-gangs-cost

[6] Cruz, José. “Maras and the Politics of Violence in El Salvador,” in J.M Hazen and Dennis Rodgers (eds.), Global Gangs: Street Violence Across the World, (Minneapolis, 2014) 129.

[7]Cruz, José. “Central American maras: from youth street gangs to transnational protection rackets.” Global Crime 11, no. 4 (2010): 394.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Rodgers, Dennis, Robert Muggah, and Chris Stevenson. “Gangs of Central America: causes, costs, and interventions,” Small Arms Survey, (2009) 7.

[10] Ibid.

[11] U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act,” 104th Congress, 1996, Title III.

[12] Cruz, José. “Central American maras: from youth street gangs to transnational protection rackets.” Global Crime 11, no. 4 (2010): 385.

[13] Rodgers, Dennis and Adam Baird. “Understanding gangs in contemporary Latin America” in Scott Decker and David Pyrooz (eds.) Handbook of Gangs and Gang Responses. New York: Wiley, 2015, 4.

[14] Cruz, José. “Maras and the Politics of Violence in El Salvador,” in J.M Hazen and Dennis Rodgers (eds.), Global Gangs: Street Violence Across the World, (Minneapolis, 2014) 131.

[15] Cruz, José. “Factors Associated with Juvenile Gangs in Central America,” in Street Gangs in Central America, ed. José Cruz, 13-65, (San Salvador: University of Central America, 2007).

[16] Hume, Mo. “Mano Dura: El Salvador Responds to Gangs.” Development in Practice 17, no. 6(2007): 745.

[17] Cruz, José. “Maras and the Politics of Violence in El Salvador,” in J.M Hazen and Dennis Rodgers (eds.), Global Gangs: Street Violence Across the World, (Minneapolis, 2014) 132.

[18] Hume, Mo. “Mano Dura: El Salvador Responds to Gangs.” Development in Practice 17, no. 6(2007): 745.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Cruz, José. “Maras and the Politics of Violence in El Salvador,” in J.M Hazen and Dennis Rodgers (eds.), Global Gangs: Street Violence Across the World, (Minneapolis, 2014) 133.

[21] Ibid 135.

[22] Cruz, José. “Central American maras: from youth street gangs to transnational protection rackets.” Global Crime 11, no. 4 (2010): 392

[23]Hume, Mo. “Mano Dura: El Salvador Responds to Gangs.” Development in Practice 17, no. 6(2007): ume, “Mano Dura,” 746

[24] DeCesare, Donna. “Documenting Migration’s Revolving Door,” Nieman Reports 60, no. 3 (2006): 26.

[25] Hume, Mo. “Mano Dura: El Salvador Responds to Gangs.” Development in Practice 17, no. 6(2007): 745.

[26] DeCesare, Donna. “The Children of War: Street Gangs in El Salvador.” NACLA Report on the Americas 32, no. 1 (July, 1998): 21-29.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Savenije, Wim. “Las Pandillas Trasnacionales Mara Salvatrucha y Barrio 18th Street: Una Tensa Combinación de Exclusión Social, Delincuencia y Respuestas Represivas.” Intra-Caribbean Migration and the Conflict Nexus (2006): 213.

[29] Ibid.

[30] “Presidente Funes exige investigación de más de 100 casos de corrupción denunciados por su gobierno,” Transparencia Activa. 7 September 2013. Accessed 18 July 2016.

[31] Moodie, Ellen. El Salvador in the Aftermath of Peace: Crime, Uncertainty, and the Transition to Democracy (Philadelphia: 2011) 205-214.

[32] “New Law Ensures Transformative Social Programs will Carry On.” Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador, 18 May 2015. Accessed 18 July 2016. http://cispes.org/blog/new-law-ensures-transformative-social-programs-will-carry?language=es

[33] Rivera, Cesar. “El Salvador: La tregua entre las pandillas y la negociacion del gobierno: lo bueno, lo malo, y lo feo – I,” in Seguridad Ciudadana en las Americas: Tendencias y Politicas Publicas: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2013.

[34] Kawas, Jorge. “El Salvador: Funes denies direct involvement in gang truce.” Pulsamérica. 27 Jan 2014. Accessed 18 July 2016. http://www.pulsamerica.co.uk/2014/01/el-salvador-funes-denies-direct-involvement-in-gang-truce/

[35] Gonzalez B., Mabel, “El Salvador’s Gang Truce: A Lost Opportunity?” OpenSecurity. 18 May 2015. Accessed 18 July 2016. https://www.opendemocracy.net/opensecurity/mabel-gonz%C3%A1lez-bustelo/el-salvador%E2%80%99s-gang-truce-lost-opportunity

[36] Ibid.

[37] “Secret Mass Graves Threaten El Salvador’s Hard-Won Gang Truce.” NBC News. 29 Jan 2014. Accessed 18 July 2016. http://worldnews.nbcnews.com/_news/2014/01/29/22491097-secret-mass-grave-threatens-el-salvadors-hard-won-gang-truce?lite

[38] “Murdered schoolboys shake El Salvador’s gang truce: Peace between rival outfits stands on knife-edge after discovery of mass grave.” Daily Mail UK. September 9 2012. Accessed 18 July 2016. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2200531/Murdered-schoolboys-shake-El-Salvadors-gang-truce-Peace-rival-outfits-stands-knife-edge-discovery-mass-grave.html

[39] Lakhani, Nina. “Trying to end gang bloodshed in El Salvador,” Al Jazeera America, 19 January 2015.

[40] Gagne, David. “El Salvador’s Forces Kill 346 Gang Members this Year.” Insight Crime. 1 June 2016. Accessed 18 July 2016. http://www.insightcrime.org/news-briefs/346-gang-members-dead-at-hands-of-el-salvador-police-2016

[41] Buncombe, Andrew. “El Salvador: Inside the world’s deadliest peacetime country.” Independent UK. 3 June 2016. Accessed 18 July 2016. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/el-salvador-inside-the-worlds-deadliest-peacetime-country-a7062426.html

[42] Martínez, Oscar. “La Fiscalía Acusa a Nueve Polícias por una Bala en la Finca San Blas.” El Faro. 18 July 2016. Accessed 18 July 2016. http://www.elfaro.net/es/201607/salanegra/18956/La-Fiscal%C3%ADa-acusa-a-nueve-polic%C3%ADas-por-una-bala-en-la-finca-San-Blas.htm

[43] Ibid.

[44] “Plan El Salvador Seguro: Resúmen Ejecutiva.” 15 Jan 2015. Consejo Nacional de Seguridad Ciudadana y Convivencia. Accessed 18 July 2016. http://www.presidencia.gob.sv/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/El-Salvador-Seguro.pdf

[45] “Special Report: El Salvador Enacts Emergency Security Measures Against Gang Violence.” Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador. 2016 May 11. Accessed 18 July 2016. http://cispes.org/article/special-report-el-salvador-enacts-emergency-security-measures-against-gang-violence

[46] LaSusa, Mike. “El Salvador Mayor’s Arrest Highlights Gangs’ Political Clout.” Insight Crime. 10 June 2016. Accessed 18 July 2016. http://www.insightcrime.org/news-analysis/el-salvador-mayor-arrest-highlights-gangs-political-clout

[47] Ibid.

[48] Interview with Arnulfo Franco, director of CORDES. 05 July 2016.

[49] Interview with Francisco Pacheco, director of RENASE, 15 July, 2016.

[50] “Informe Testimonial de Desplazamiento Forzado en El Salvador Enfocado en Niñez, Adolescencia y Juventud.” June 2016. Mesa de Sociedad Civil Contra el Desplazamiento Forzado por Violencia Generalizada y Crimen Organizado en El Salvador. Accessed 18 July 2016. http://cristosal.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Informe-testimonial-sobre-desplazamiento-forzado.pdf\

[51] Muggah, Robert. “It’s official: San Salvador is the murder capital of the world.” Los Angeles Times. 2 March 2016. Accessed 18 July 2016. http://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-0302-muggah-el-salvador-crime-20160302-story.html

[52] “El Salvador, Deadliest Nation in 2015 sees Lull in Violence.” The Washington Post. 3 July 2016. Accessed 5 July 2016.

[53] Martínez, Carlos. “Pandillas Caminan Hacia un Frente Común ante medidas extraordinarias.” 5 July 2016. Accessed 18 July 2016. http://www.elfaro.net/es/201607/salanegra/18899/Pandillas-caminan-hacia-un-frente-com%C3%BAn-ante-medidas-extraordinarias.htm

[54] Morales, Napoleón. “Mareros asesinan al alcalde de Tépitan del partido FMLN en San Vicente.” La Página. 9 July 2016. Accessed 18 July 2016.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Foley, Elise and Roque Planas. “El Salvador Deemed too Dangerous for Peace Corps, but not for Deportees.” The Huffington Post. 12 Jan 2016. Accessed 18 July 2016. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/el-salvador-peace-corps-deportation-raids_us_56951d56e4b09dbb4bac94ab