Venezuelan Turmoil Insinuates an Uncertain Future for ALBA

By Sheldon Birkett, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF of this article, click here.

The declared exit of Venezuela from the Organization of American States (OAS), the suspension of Venezuela from MERCOSUR in 2016 for its failure to “conform” to the bloc’s “democratic principles,” and the unification of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) in defiance of a United States partisan resolution, raises the question whether the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA) can be an alternative to the OAS as both a social and economic platform for Venezuelan dialogue.[i][ii] The OAS Permanent Council meeting on March 28, 2017, cited reasons to invoke the Inter-American Charter against Venezuela. The meeting revealed the demarcated political divide within the OAS; for instance, Saint Lucia voted yes to invoke the charter, whilst simultaneously benefiting from the Venezuelan Petrocaribe initiative under ALBA.[iii] The Canadian ambassador to the OAS, Jennifer May Loten, took one of the strongest stances to invoke the charter against Venezuela. Loten denounced the claim that the United States rallied support against Venezuela,[iv] and called for a truth commission to be formed to “guide liberation of political prisoners [in Venezuela].”[v]

It is unclear if the principles of solidarity, complementarity, justice, and cooperation of Bolivarian Alliance will persist amongst political dissidence. Foreign intervention in the relationship between Venezuela’s popular power and the state is signaling the beginning of the end for Bolivarian “participatory and protagonistic democracy”.[vi]

ALBA is an intergovernmental organization focused on establishing social, economic, and political cooperation among its member states. ALBA is inspired by Simón Bolívar’s revolutionary ideal of greater solidarity and integration in Latin America. Bolivar believed in a unified South American nation ruled by one caudillo adherent to the opposition of foreign imperialist states.[vii] ALBA was initially established in 2004 between Venezuela and Cuba, under the leadership of both Hugo Chavez and Fidel Castro, to facilitate the exchange of Cuban medical services for Venezuelan petroleum. Today, ALBA consists of eleven member states — St. Vincent & Grenadines, Ecuador, Antigua & Barbuda, Dominica, Saint Lucia, Grenada, Saint Kitts & Nevis, Nicaragua, Bolivia, Venezuela and Cuba — and three observer states, Haiti, Iran, and Syria, with Suriname admitted as a guest member in 2012.[viii]

The bloc’s monetary union showcases the autonomy of 21st century south-south cooperation from Washington’s political influence.[ix] The principal strength of ABLA is the SUCRE. The SUCRE is a regional unit of account, that allows the facilitation of regional trade without being dependent on the United States dollar. The central purpose of the SUCRE, as an international unit of account, is to stabilize current account transactions among member-states. Balanced national current account, and ergo capital account, transactions between countries are central to elevating unfair shifts in purchasing power due to unbalanced trade.[x] In effect, balanced current account transactions between ALBA member countries would increase domestic demand and direct investment, without having to be at the mercy of US currency speculation for importing and exporting goods and services. In addition to opening up room for domestic investment, through a balanced current account, member countries’ foreign debts are self-contained within ALBA. Central to the self-containment of the SUCRE, is the fact that member countries would not owe debts to foreign countries, instead they would owe credit or debit to ALBA’s monetary bloc. The endogenous structure of ALBA’s foreign currency exchange, through a regional currency, denominates the bloc as financially self-contained from U.S. currency manipulation.

ALBA is also approaching monetary unity in partnership with socio-economic development initiatives.[xi] ALBA’s initiatives include, Cuba’s Sí, Se Puede, Nicaragua’s Programa Hambre Cero, and Venezuela’s PetroCaribe focusing on literacy, nutrition, communications, and fair economic cooperation.[xii] Perhaps the most significant of these initiatives has been PetroCaribe, a program that provides Caribbean states their energy needs at a fair and reasonable rate. Under Petrocaribe the state oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), provides 100 percent of member countries’ energy needs at market price, with nearly 50 percent of consumption loans payable over 25 years at an interest rate of two percent.[xiii] Venezuela’s PetroCaribe initiative is fiscally more competitive, and attractive, than other alternatives for the Caribbean community.

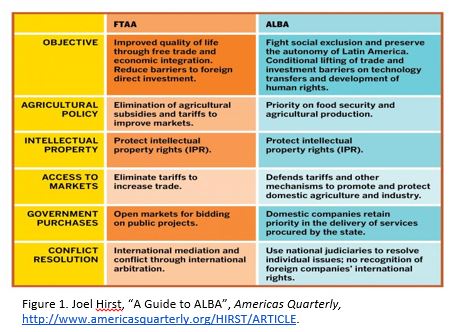

Unlike the MERCOSUR trade bloc, ALBA promotes democratic trade agreements in which the autonomy of member states is of central importance (See Figure 1). ALBA was created in 2004 as an alternative to the Free Trade Agreement of the Americas (FTAA), but has since developed into an ideological alliance.[xiv] At the 14th ALBA summit on March 6, 2017, Venezuela President Maduro remarked “[the] great challenge of this generation and the coming generation will be to have the same capacity of achievement, construction, and success in building a productive model that will give us independence.”[xv] Maduro outlined the need for greater south-south cooperation amongst Latin American countries, speaking against the harsh neoliberal policies instituted during the 1980’s, famously known as Latin America’s “lost decade.” ALBA’s autonomy is essential for member states to sustain progressive integration, and to maintain economic autonomy from countries that have a superior productivity advantage. However ALBA has to set-up its game, as Venezuela’s top three largest trading partners are the United States, China, and India, none of which are ALBA member states.

Misguided US Sanctions on Venezuela: What Future for ALBA?

The current challenges facing Venezuela come at a time when Latin America’s political climate is turning sour. The days of military interventions instituting “puppet” regimes with support of the United States have drawn to a close since the failed coup attempt against former President Hugo Chavez in 2003. Though, the United States still uses political and economic leverage against Venezuela to further degrade the country’s preferential access to its ubiquitous oil reserve. In May 2017, Goldman Sachs investment bank bought $2.8 billion worth of bonds from Petroleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) for 31 cents on the dollar, Goldman Sachs only paid $865 million for the bonds.[xvi] The oil bonds purchased by Goldman mature in 2022,[xvii] therefore Goldman took advantage of Venezuela’s dire economic situation, and the value gained on the bonds could be used for political leverage over Venezuela if the country decides to buy back the PDVSA issued bonds. Furthermore, in January 2017, Obama renewed an executive order declaring Venezuela as a threat to U.S. national security.[xviii] More recently, the Trump administration is considering imposing sanctions against the state owned Venezuelan oil company PDVSA.[xix] The United States can either place a blanket ban on all Venezuelan oil imports, or bar PDVSA from bidding on United States government contracts.[xx] Given the United States economic and political hegemony over the hemisphere, it is entirely possible that the United States could use its economic leverage over Venezuela to its own advantage. Unless other ALBA countries utilize the SUCRE as a means of balancing Venezuela’s trade deficit, the deflationary effect on the value (not price level) of the Bolivar fuerte will continue.

Building on Hugo Chávez socialist Bolivarian ideals based on “solidarity, in fraternity, in love, in justice, in liberty, and [in] equality,”[xxi] ALBA’s philosophy encapsulates progressive socialism for Latin America in the 21st century. ALBA’s trade initiatives, such as PetroCaribe, present preferential trade for energy with low interest financing.[xxii] Although ALBA’s trade initiatives can aid the Venezuelan economy, Venezuela’s fiscal and monetary policies fail to address export dependency as the root cause of Venezuela’s economic instability. On Venezuela’s fiscal policy, expenditures mainly consist of increases in public sector spending financed directly through PDVSA. Additionally, the National Development Fund and the joint China-Venezuela Fund provide additional financing for the country’s social programs.[xxiii] Taxation in Venezuela has increased on corporate and income tax from 2 percent of GDP in 1999 to 3.2 percent of GDP in 2006: Venezuela’s sales tax increased from 9 percent to 12 in 2009.[xxiv] State-run PDVSA financing and taxation reveals that Venezuela’s fiscal policy is cyclical in nature. After 2003, Venezuelan monetary policy has focused on increasing aggregate demand. Strategies have included reducing interest rates and instituting price controls on basic consumption items, which account for 30 percent of the 2009 Consumer Price Index (CPI) basket,[xxv] ensuring that low income households’ consumption needs will be provided. Stringent price controls have increased government subsidies, to mark-up the loss of producer surplus on price-controlled goods, which has further increased the inflation rate.[xxvi]

Despite Venezuela’s heterodox fiscal and monetary policies, hyperinflation also arose because of a steep decline in the price of oil, illustrative of the fact that Venezuelan oil accounts for 95 percent of the country’s export earnings. In 2014 oil was over $100 USD per barrel, while in early 2016 it was as low as $33 USD per barrel.[xxvii] The rapid fall in the price of oil reduced the amount of foreign reserves available for Venezuela. This limited availability of foreign currency exchange for non-essential imports, resulted in a higher exchange rate for select imports.[xxviii] Additionally, the reduction in the availability of foreign currency reserves led to a budget shortfall, and the Venezuelan state had to fill in the budget gap by printing money. Inturn, this resulted in hyperinflation. Furthermore, the Venezuelan government nationalized monopolistic private enterprises to enforce price controls that are favorable towards increased aggregate demand, while simultaneously turning a blind eye towards the economic realities of hyperinflation eating away at domestic investment. In 2007 Venezuela nationalized four major oil projects in Orinoco crude belt, and in 2010 Venezuela nationalized nitrogen fertilizer producer Fertinitro. Currently Venezuela is seeking to nationalize and institute price controls on Empresas Polar, which is the largest private food producer in Venezuela.[xxix] Though, simply nationalizing domestic industry will not tame the flight of capital because of preferential exchange rates abroad.

In addition to the price control, the Venezuelan government fixed the exchange rate in February 2016 to 10 bolívar fuerte per U.S. dollar to control for inflation. The fixed exchange rate has only further exacerbated inflation, as many of Venezuela’s essential food imports have been sold to Colombia through the black market or private exchange markets. The export of essential food imports from Venezuela is occurring because the black-market exchange rate is close to 4,000 bolívars per U.S. dollar.[xxx] Therefore, it is more lucrative to export goods outside the Venezuelan state.

Inflation led to an Increased Pressure on Public Policies

The increased pressure on debt-service payments, fixed exchange rate, price controls, and declining foreign currency reserves has led Venezuela to consider paying its creditors at the expense of funding public services. The Venezuelan state is also considering buying back government issued bonds and selling them at a discount price to service its debt, such as how Goldman Sachs bought Venezuelan bonds at a discount of 31 cents on the dollar. It is projected that the Venezuelan state can raise between $5 USD billion and $6 USD billion by reselling government bonds at a discount.[xxxi] It is likely that the Venezuelan government will buy back these bonds as “Venezuela has gone to extraordinary lengths to keep servicing its debt.”[xxxii]

Mismanagement of the Venezuelan economy is now diminishing the availability of domestic credit. In the early 2000’s the National Assembly favored lower interest rates to increase the availability of domestic credit for those on the lower end of the income scale.[xxxiii] Now it seems Venezuela’s policy of low interest rates to “kick start” the economy has been sabotaged by hyperinflation, eroding the purchasing power of each bolívar.

Although ALBA was conceived as a progressive left-wing intergovernmental initiative to help balance trade inequalities in the bolivarian economies, it has failed the Venezuelan economy. Venezuela is far too dependent on oil exports. In response to this dependency the Venezuelan government adopted a two-tiered exchange rate system as an effort to protect critical imports while stabilizing foreign exchange.[xxxiv] Despite Venezuelan policymakers best efforts, the country has experienced severe stagflation, with an excess contraction of more than 10 percent in output.[xxxv] The contraction in the Venezuelan economy has resulted in a current account[xxxvi] deficit of $5.1 USD billion as of 2015 from a current account surplus of $5.7 USD billion a year earlier.[xxxvii] In addition to its current account deficit, high inflation, rising unemployment, and volatile exchange rate; the value of Venezuela’s primary export, oil, is less than half that is required to finance their fiscal account spending.[xxxviii] Due to price controls, restrictions on imports, and the falling price of oil, the country is experiencing a hyperinflation rate of over 481 percent coupled with a 17 percent unemployment rate.[xxxix] In addition, the government roughly owes $7 billion USD on a debt of $30 billion USD to China.[xl] Though exact statistics are disputed, it is evident that the Venezuelan economy is facing a dire situation. Given Venezuela’s stark economic reality, Maduro’s options are increasingly limited. Either Maduro can default on the government debt, or reduce price controls and import limitations in an effort to regain investor confidence in the bolívar.

But the predicament may not be as bad as it appears. Despite the critical economic situation, it is important to remember that Venezuela owes no external debt to the International Monetary Fund and sits on the world’s largest oil reserves.[xli] Therefore, by collaborating with ALBA member countries, restructuring its import regime, and reselling its foreign debt through open market operations (e.g. Ecuador’s 2009 repurchase of defaulted foreign bonds),[xlii] it is possible that Venezuela would be able to escape its current economic predicament.

Political Uncertainty Continues

In addition to the choices made by Venezuelan policymakers, the country’s economic fate is contingent on the political situation it is now facing. On July 16, 2017 roughly 7.186 million Venezuelans protested President Maduro’s constituent assembly election on July 30th, many protestors are in favor of the current constituent assembly.[xliii] This followed from Maduro’s call in April for a “constituent assembly” to write a new constitution, after opposition protests resulted in 35 deaths.[xliv] Maduro’s call to reevaluate the constitution comes at a critical time when progressive dialogue is needed within the nation’s political system. With approval ratings below 30 percent, the political future of Maduro and his party, the PSUV, is far from certain.[xlv]

But all is not lost for Venezuela. One bastion of hope is ALBA, whose past policy initiatives demonstrate that it is possible for countries in Latin America to cooperate on progressive economic policy. Given the evolving political and economic situation in Venezuela, it is imperative for the Maduro administration to reevaluate regional economic cooperation among the Bolivarian nations. Though, implementing effective economic policy may be easier said than done, as former president Hugo Chávez expressed “only by way of socialism [can we improve the situation] little by little. The terrible inequality created during 100 years of capitalism will not be removed in one year or in ten. [It will not take] as much as 100 years, but at least several decades [will be necessary].”[xlvi]

By Sheldon Birkett, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Additional editorial support provided by Clement Doleac, Senior Research Fellow, Jordan Bazak, Research Fellow, and Jack Pannell and Alexia Raun, Research Associates at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Featured Image: Venezuela Protests Flag Taken From: Wikimedia

[i] Patricio Zamorano, “The OAS and the Crisis in Venezuela: Luis Almagro and his Labyrinth”, Council on Hemispheric Affairs, April 28, 2017, https://coha.org/the-oas-and-the-crisis-in-venezuela-luis-almagro-and-his-labyrinth/.

[ii] “Caracas To ‘Vexit’ From OAS – But Where Do CARICOM and OECS Stand?” The Voice, April 29, 2017, http://thevoiceslu.com/2017/04/caracas-vexit-oas-caricom-oecs-stand/.

[iii] Mercedes Hoffay, & Karen Mustiga, “OAS and Venezuela: Another Contested Vot nut with Recommendations,” Latin America Goes GLOBAL, March 29, 2017, http://latinamericagoesglobal.org/2017/03/oas-venezuela-another-contested-vote-recommendations/.

[iv] Jeanette Charles, “OAS Fails to Reach Consensus on Venezuela Suspension in Latest Extraordinary Session,” venezuelanalysis.com, March 28, 2017, https://venezuelanalysis.com/news/13009.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Joel Hirst, “A Guide to ALBA”, Americas Quarterly, http://www.americasquarterly.org/HIRST/ARTICLE.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] ALBA Monetary Bloc: ALBA has an independent bank in Caracas and its own currency, the SUCRE, pegged to $1.25 USD.

[x] Martin Riese, “Reforming the Global Financial Architecture A Comparison of Different Proposals -6.2 John M. Keynes: Proposal for an International Currency Union,” Johannes Kepler Universitat Linz, October 2008,

[xi] Shawn Hattingh, “ALBA: Creating a Regional Alternative to Neo-liberalism?,” Monthly Review, February 8, 2008, https://mronline.org/2008/02/07/alba-creating-a-regional-alternative-to-neo-liberalism/.

[xii] Joel Hirst, “A Guide to ALBA”, Americas Quarterly, http://www.americasquarterly.org/HIRST/ARTICLE.

[xiii] Alejandro Bendaña, “Alternative financing for development: Venezuela and ALBA,” CADTM, May 22, 2008, http://www.cadtm.org/spip.php?page=imprimer&id_article=3390.

[xiv] Joel Hirst, “A Guide to ALBA”, Americas Quarterly, http://www.americasquarterly.org/HIRST/ARTICLE.

[xv] “ALBA: An example of successful South-South Cooperation,” New Delhi Times, May 15, 2017, https://www.newdelhitimes.com/alba-an-example-of-successful-south-south-cooperation123/.

[xvi] “Goldman Sachs makes an irresponsible deal with the corrupt Venezuela regime,” The Washington Post, June 4, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/goldman-sachs-makes-an-irresponsible-deal-with-the-corrupt-venezuela-regime/2017/06/04/f3e3994c-47a8-11e7-bcde-624ad94170ab_story.html?utm_term=.7b9e88138e42.

[xvii] Tom Buerkle, “In Venezuela, Goldman Sachs Found a Hot Deal and a Moral Mess,” The New York Times, May 30, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/30/business/dealbook/venezuela-bonds-goldman-sachs.html.

[xviii]“Obama Declares Cuba and Venezuela National Security Threats,” Telesur, January 13, 2017, http://www.telesurtv.net/english/news/Obama-Declares-Cuba-and-Venezuela-National-Security-Threats-20170113-0024.html.

[xix] Girish Gupta, & Matt Spetalnick, “Exclusive: U.S. Considers possible sanctions against Venezuela oil sector – officials,” Reuters, June 4, 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-venezuela-pdvsa-exclusive-idUSKBN18V08P

[xx]Girish Gupta, & Matt Spetalnick, “Exclusive: U.S. Considers possible sanctions against Venezuela oil sector – officials,” Reuters, June 4, 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-venezuela-pdvsa-exclusive-idUSKBN18V08P

[xxi] Ozgur Orhangazi, “Contours of Alternative Policy Making in Venezuela,” Review of Radical Political Economics 46, no. 2 (2014): 230.

[xxii]Ibid, 228.

[xxiii] Ibid, 225.

[xxiv] Ibid, 225.

[xxv] Ibid, 226.

[xxvi] Ludwig Von Mises, “Inflation and Price Control,” Mises Institute, May 27, 2005, https://mises.org/library/inflation-and-price-control.

[xxvii] Theodore Cangero, “Venezuela: Socialism, Hyperinflation, and Economic Collapse,” American Institute For Economic Research, March 1, 2017, https://www.aier.org/research/venezuela-socialism-hyperinflation-and-economic-collapse.

[xxviii]Ibid, 226.

[xxix]“Factbox: Venezuela’s nationalizations under Chavez,” Reuters, October 7, 2012, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-venezuela-election-nationalizations-idUSBRE89701X20121008 .

[xxx] Theodore Cangero, “Venezuela: Socialism, Hyperinflation, and Economic Collapse,” American Institute For Economic Research, March 1, 2017, https://www.aier.org/research/venezuela-socialism-hyperinflation-and-economic-collapse.

[xxxi] Julie Wernau, & Kejal Vyas, “Venezuela Poses Investor Dilemma,” The Wall Street Journal, June 5, 2017.

[xxxii]Ibid.

[xxxiii] Ozgur Orhangazi, “Contours of Alternative Policy Making in Venezuela,” Review of Radical Political Economics 46, no. 2 (2014):226.

[xxxiv] Ibid.

[xxxv] Ibid.

[xxxvi] Current Account: exports minus imports plus net factor income and net transfers.

[xxxvii] “Venezuela Current Account,” Trading Economics, http://www.tradingeconomics.com/venezuela/current-account.

[xxxviii] “Venezuela,” The World Bank Group, May 2, 2017, http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/venezuela/overview

[xxxix]“Venezuela’s worst economic crisis: What went wrong?,” Aljazeera, May 3, 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2017/05/venezuela-worst-economic-crisis-wrong-170501063130120.html.

[xl] Robert Khan, “Global Economics Monthly: May 2016,” Council on Foreign Relations, May 4, 2016, https://www.cfr.org/report/global-economics-monthly-may-2016.

[xli] Ozgur Orhangazi, “Contours of Alternative Policy Making in Venezuela,” Review of Radical Political Economics 46, no. 2 (2014): 226.

[xlii] “Ecuador’s winning strategy,” The Economist, June 17, 2009, http://www.economist.com/node/13854456

[xliii] “Over 7 million Venezuelans tell Maduro ‘no’,” Latin News, July 17, 2017.

[xliv]Nathan Crooks & Fabiola Zerpa, “Why Venezuela May Change Its Constitution for the 27th Time,” Bloomberg, May 9, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/politics/articles/2017-05-09/why-venezuela-may-get-its-27th-constitution-quicktake-q-a.

[xlv]“Political Crisis in Venezuela,” Council on Foreign Relations, March 30, 2015, https://www.cfr.org/report/political-crisis-venezuela.

[xlvi] Ozgur Orhangazi, “Contours of Alternative Policy Making in Venezuela,” Review of Radical Political Economics 46, no. 2 (2014): 237.