The Two Worlds of Buenos Aires: Macri’s Legacy of Inequality

[This article has received very minor edits in response to valid points raised in the comments. Please see COHA’s comment below to see what was edited]

Inequality is nothing new in Latin America; the region has long occupied the unenviable position of being considered the most unequal area in the world. However, the human face of inequality is nowhere more apparent than in Buenos Aires, the capital of Argentina. [1] Buenos Aires is a study in contrasts: the splendid Libertador Street, punctuated with art museums, luxury malls, and expensive apartments, stands at points directly across the train tracks from the improvised housing of the villas miserias, or shantytowns. Below Rivadavia Street, as the noted Argentine novelist Jorge Luis Borges put it, “the South begins,” a land of impoverished suburbs and slums.

Buenos Aires is a maze of overlapping jurisdictions. The metro area numbers some 13 million people, nearly 40 percent of the country’s population, but the city’s mayor, Mauricio Macri, presides over a jurisdiction which includes just 3 million residents. The problem has proven too much for Macri, who has been unable to develop a working relationship with either provincial or national governments. Moreover, Macri and his Propuesta Republicana Party (Republican Proposal, PRO) seem primarily interested in projects that benefit the affluent, often neglecting the issues of poverty alleviation, environmental cleanup, and improvement of substandard housing. The people of Buenos Aires deserve better. Only with immediate and decisive action can improvement come for the lived experience of the city’s poor.

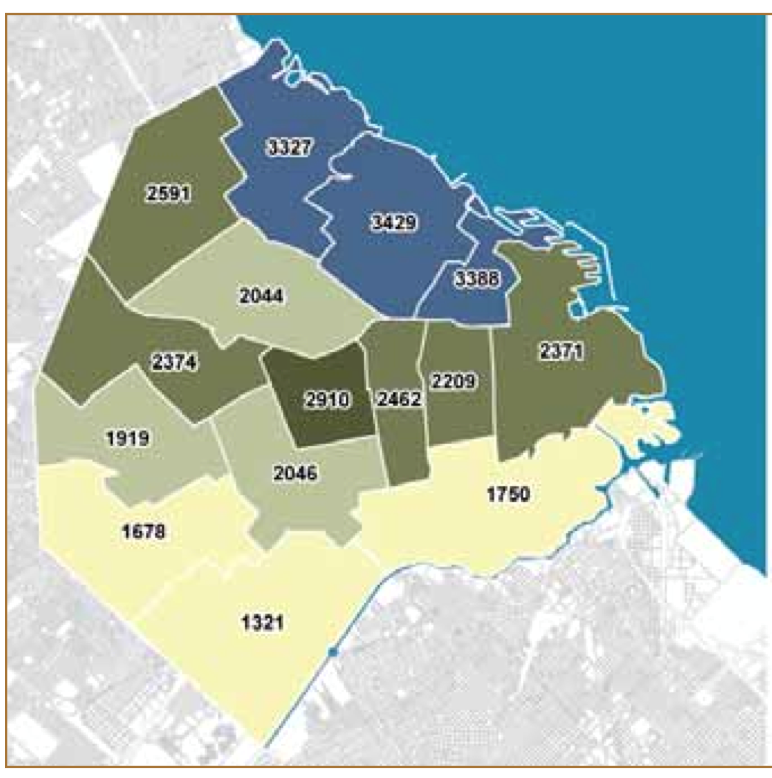

The lines of inequality are starkly delineated in the city, following the North (rich) and South (poor) gradient (see Figure 1). Levels of income disparity in Buenos Aires have grown steadily, along with a 35 percent jump in poverty in the Greater Buenos Aires area, over a 16 year period. Poverty rates rose from 12.7 percent in 1986 to 49.7 percent of the population in 2002, just after Argentina’s economic crisis, according to government statistics. U.N. Habitat estimated the city’s Gini coefficient, a measure of inequality with 0 being total equality, everyone with the same income, and 1.0 being perfect inequality, one person has all the income, at .52 in 2005. This measure, compared to Quito’s .49 and London’s .34, places Buenos Aires in the category “among the most unequal in the world” according to the United Nations. [2] The wealth of the highest decile of the population of the city is equal to 28.3 times that of the poorest. Another way of capturing this inequality is to look at city real estate prices. The cost of one square meter of land in a rich neighborhood is 116 percent higher than a meter in a poor one. [3] As many as 10 percent of the city’s residents live in informal and improvised housing, lack access to public services, and live in crime-riddled communities. [4] These problems reflect dire circumstances, but the city’s government has many of the necessary tools to successfully address them.

Source: Buenos Aires City Government – http://www.ssplan.buenosaires.gov.ar/MODELO%20TERRITORIAL/WEB/modelo_territorial.html

Overlapping Jurisdictions

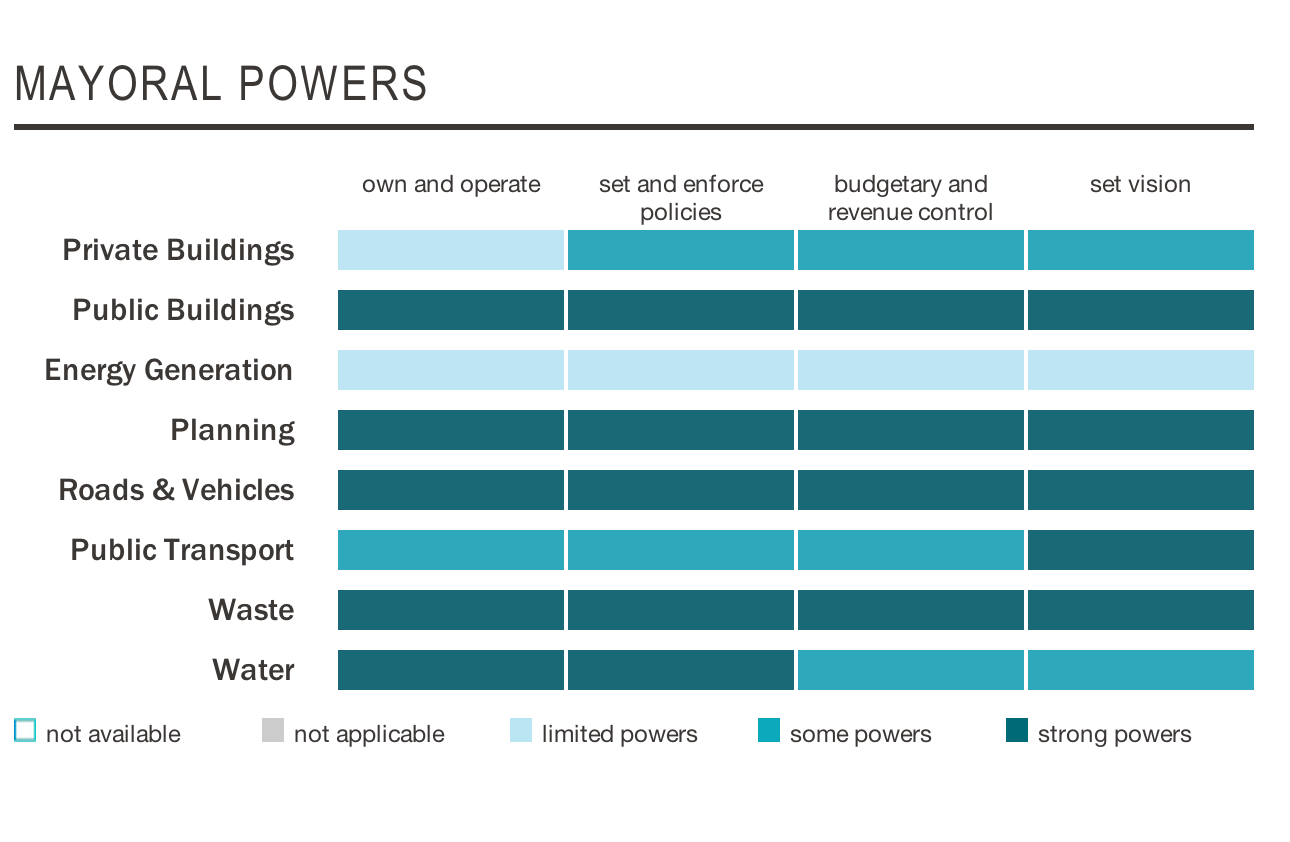

Buenos Aires has been an autonomous region since 1996, when the national government gave up its control over the appointment of the city’s mayor. Today the Buenos Aires mayor is regarded as the third most important political position in the country, after the president and the governor of Buenos Aires province. [5] Macri, scion of a wealthy family and former manager of the popular Boca Juniors soccer club, took office in 2007 after an effective electoral campaign that portrayed him as “business friendly”. The position of mayor is a powerful one, as shown by Figure 2, affording Macri a great deal of independence.

Source: C40 Cities – Climate Leadership Group – http://c40.org/c40cities/buenos-aires

Macri is also the country’s main opposition leader, and this status has figured into his drive to keep the city of Buenos Aires fiercely autonomous. Macri’s policies have moved closer and closer to practices of “city diplomacy,” in which cities, as opposed to central governments, engage in international diplomacy. Scholar Roger Van der Plujim notes that “[i]n instances where local interests are very much represented by central governments, the perceived need by cities to engage in city diplomacy is more limited than in those instances where local interests are less represented.” [6] Essentially, if city leaders do not feel that their interests are represented at the national level, they increasingly have the power and inclination to seek support internationally. On September 17, at an address at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington D.C., Carlos Pirovano, Economic Development Advisor to Mayor Macri, noted that his administration does not even hold meetings with the country’s central government, lead by Christina Fernández de Kirchner, nor with the provincial authorities of Governor Daniel Scioli. Clearly, the local interests of Buenos Aires are not represented at the national level. Following the framework of Van der Plujim, city diplomacy would then become much more important for Buenos Aires, which must look beyond the national government for diplomatic support. Pirovano’s visit to the United States indicates that Macri’s city government has begun to do just that.

These steps are allowing the Buenos Aires city government to set its own terms without having to negotiate with a complicated set of national actors. Macri has the institutional and diplomatic power as mayor to enact sweeping changes on addressing poverty issues in the city. However, he has made neither just nor efficient use of the power at his disposal, and has failed to address the problems the city faces.

Fundamentally, Macri has spent his time and the city government’s funds on urban planning projects that benefit already well-to-do Argentines. As William Kinney noted in his piece, “COHA Spotlights CSIS Roundtable Discussion with Macri’s Economic Advisor” for the Council on Hemispheric Affairs, Macri’s strategy for urban development has revolved around designating different “districts” within the city for a certain categories of economic activity. The artistic neighborhood of Palermo, for instance, was designated as a “film district,” with tax and infrastructure incentives for further development of the film industry. Carlos Pirovano highlighted the importance of these initiatives, especially in the southern neighborhood of Parque Patricios, which was designated as a “technology district.” This neighborhood, which is one of the city’s poorest, has seen a 200 hectare development of office buildings and the growth of technology sectors, with 158 new businesses moving into the zone. [7] Pirovano also noted that increased security in Parque Patricios had led to reduced use of “paco” (crack cocaine) in the area.

While these are worthy enough projects, the jobs created are largely destined for well-educated middle and upper-class Argentines, not those who live in the neighborhood, severely limiting any poverty-alleviation impact from these measures. Indeed, many of the development districts, like the film district in Palermo, are located in already affluent areas of the city. In addition, this emphasis on the development of individual districts has corresponded with a cutback in funds available for other important projects.

The proposed 2014 city budget indicates the lowest spending on social housing in the last decade, a 19 percent reduction from last year and part of a trend of declining funds for those living in improvised and informal housing. [8] This budget received harsh criticism from Daniel Filmus, former senator for the ruling Frente Para la Victoria (Front for Victory, FPV) party, who charged that the measure could only result in “lowering salaries, lowering social spending, and increasing debt.” [9] Meanwhile, the budget for the city’s Ministry of Social Development will also be reduced by $20 million USD for next year. These cuts have been put into place despite the fact that it is estimated that 350,000 people in the city are living in a situation of “housing emergency.” [10] Educational organizations in the city, like Igualdad Educativa (Education Equality), have also criticized the 2013 budget’s emphasis on subsidies for private schools. The sums destined for private schools exceeded the funds allocated to the Subcommittee for Education Equality, an organization charged with increasing inclusion and equality in public education in Buenos Aires, indicating a powerfully regressive approach to education.

Macri is failing in other ways. Lamentably, his government has dragged its feet on the logistics of a cleanup of the Matanza -Riachuelo River along Buenos Aires’ southern border. The site is infamous, recently mentioned on Time Magazine’s list of 10 most polluted places. [11] A dumping ground for tanneries and other industrial sites, the Riachuelo is heavily contaminated with zinc, lead, copper, nickel, and chromium. Many of the two million people who live along its banks rely on the river for their drinking water, putting their health in jeopardy. [12] While cleanup efforts have begun with an edict from the country’s Supreme Court and with the help of $840 million USD from the World Bank, efforts to relocate more than 2,400 families away from unsafe living conditions on the banks have been stalled by bureaucratic infighting. Furthermore, a recent report by Acumar, a local government agency, noted the reappearance on the banks of more than 70 percent of the waste that previously had been cleaned from the river’s banks. [13] Finally, the city has not yet addressed the sad fact that there are only 35 ACUMAR inspectors and 100 Environmental Protection Agency inspectors for the more than 2,345 companies located along the river in the city’s territory, slowing the pace of clean-up work. [14] The effort could last nine more years and the total cost could be in the billions of dollars. These derelictions of duty on the part of the PRO in Buenos Aires take on grander significance when their aspirations toward national office are taken into account.

Macri’s Poltical Future

Macri’s PRO is currently the fourth-largest political party in Argentina, after Peronism, the social liberalism of the Unión Cívica Radical party, and the socialist Frente Amplio Progresista party. [15] The PRO party’s political victories in Buenos Aires demonstrate that Macri has caught the imaginations of Argentina’s urban elite. The trouble is, however, that the mayor of Buenos Aires is clearly more concerned with image and “business-friendliness” than with the real needs of his poorest constituents. The city’s website is dedicated to burnishing Macri’s self image, presenting a sunny image of the city where on every street corner, happy Buenos Aires residents bask under banners declaring “En todo estás vos” (you are in the middle of everything). Perhaps Macri believes this, perhaps he thinks that the benefits of his urban planning projects will “trickle down” to the city’s poor, but up to this point, it does not appear to be working. At rallies and other events, youth from the city of Buenos Aires chant “Macri, basura, se fue la dictadura” (Macri, you’re trash, the dictatorship is gone). If Macri has future political aspirations, as he apparently does, he must learn to incorporate the needs of those outside his rosy bubble of “modernity.”

Thomas Abbot, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action

For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action

[1] “Buenos Aires.” C40 Cities. Accessed November 18, 2013. http://www.c40cities.org/c40cities/buenos-aires

[2]“State of the World’s Cities 2010/2011: Bridging the Urban Divide” UN Habitat. 2008

[3] “2010-2060: Modelo Territorial Buenos Aires.” Ministerio de Desarrollo Urbano de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. 2011.

[4] Ibid. Auyero. 2010

[5] Murph, Martin. “Profile: Mauricio Macri.” BBC. June 25, 2007. Accessed November 4, 2013. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/6222126.stm

[6] Van der Plujim, Rogier. “City Diplomacy: The Expanding Role of Cities in International Politics.” Netherlands Institute of International Relations. April, 2007

[7] Smith, Romina. “Distrito Tecnológico: Parque Patricios se Transforma: ya se radicaron 158 empresas.” Clarín. September 8, 2013. Accessed November 18, 2013. http://www.clarin.com/ciudades/Parque-Patricios-transforma-radicaron-empresas_0_989301167.html

[8] Videla, Eduardo. “ La vivienda, con su presupuesto más bajo.” Página 12. November 11, 2013. Accessed November 18, 2013. http://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/sociedad/3-233311-2013-11-11.html

[9] “Filmus denunció que ‘el presupuesto de la ciudad es de ajuste.” Página 12. October 3, 2013. Accessed November 19, 2013. http://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/ultimas/20-230467-2013-10-03.html

[10] Ibid: Videla, November 11, 2013

[11] Walsh, Brian. “Urban Wastelands: The World’s 10 Most Polluted Places: Matanza-Riachuelo, Argentina.” Time. November 4, 2013. Accessed November 18, 2013. http://science.time.com/2013/11/04/urban-wastelands-the-worlds-10-most-polluted-places/slide/matanza-riachuelo-argentina/

[12] Herrberg, Anne. “Argentina’s filthy Riachuelo River faces clean-up.” DW. September 28, 2011. Accessed November 18, 2013. http://www.dw.de/argentinas-filthy-riachuelo-river-faces-clean-up/a-15417355

[13] “Riachuelo: Más retrocesos que avances.” La Nación. November 13, 2013. Accessed November 19 ,2013. http://www.lanacion.com.ar/1637708-sin-titulo

[14] Ibid: Herberg, November 18, 2013

[15] “Latin American Weekly Report: Modest victory fails to mask uncertain future for Kirchnerismo.” Latin News. October 31, 2013. Accessed October 31, 2013. http://www.latinnews.com/media/k2/pdf/btofe.pdf