The Last of the Mayans: Preserving Chiapas’ Indigenous Languages in the 21st Century

By Jordan Bazak, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF version of this article, click here.

On January 1, 1994, indigenous members of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) marched into the city of San Cristobal de Las Casas in the state of Chiapas, Mexico the same morning that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect.[i] This past spring, thousands of teachers belonging to the National Organization of Education Workers (CNTE) took to the streets of the nearby state capital, Tuxtla Gutierrez, to protest President Enrique Peña Nieto’s signature education reform.[ii] Separated by two decades, these movements seem to have little in common. The Zapatistas worried that a NAFTA-required constitutional amendment, which permitted the privatization of ejidos (communal lands), would lead to greater property concentration.[iii] Today’s opponents of education reform fear that new teacher evaluation requirements threaten the jobs of indigenous instructors, who are vital to communities in which many parents do not speak Spanish.[iv] Their core concern, however, was and is the same: that Mexico’s economic and social reforms have consistently neglected the values, cultures, and traditions of its native people.

Language is one of the most important components of a people’s identity and culture. Although Spanish is by far Mexico’s predominant language, 7 million Mexicans speak one of the country’s more than 60 indigenous tongues. The Zapatista Uprising brought new attention to indigenous language rights, resulting in the 2003 General Law on the Linguistic Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which guaranteed linguistic equality in education, public services, and mass media.[v] Since then, Chiapas’ indigenous languages, if not those elsewhere, have experienced remarkable stability. While it is difficult to attribute this maintenance solely to a relatively new national piece of legislation, there can be little doubt that the cultural and political awakening that preceded the law’s enactment reinforced Chiapas’ native tongues in a way that did not occur elsewhere.

Located on Mexico’s southern border with Guatemala, Chiapas is among the poorest and slowest growing states in the Mexio. Improvements in education, gender equality, and urbanization are much needed. Unfortunately, each of these changes is likely to threaten the continuity of the state’s indigenous languages. Granting greater autonomy to indigenous communities and supporting natives who migrate to urban centers would mitigate the effect of such reforms. Failure to promote inclusive development not only threatens Chiapas’ linguistic diversity but also its social order. As history has shown, if the state’s indigenous people feel marginalized by reform, they will not hesitate to defend their way of life at all costs.

The National Decline in Indigenous Languages

As of the most recent census, indigenous language speakers make up 6.6 percent of Mexico’s population, down from 10.4 percent in 1960.[1] Recently, the decline has been particularly sharp in states such as Oaxaca and Yucatan, which both have large indigenous populations. Furthermore, over the past half century, the percentage of indigenous language speakers who cannot speak Spanish (monolinguals) has been cut in half. Today, just 6 percent of Mexican teenagers speak an indigenous language of which only 8 percent are monolingual.[vi]

Chiapas’ Indigenous Languages: Staying Strong

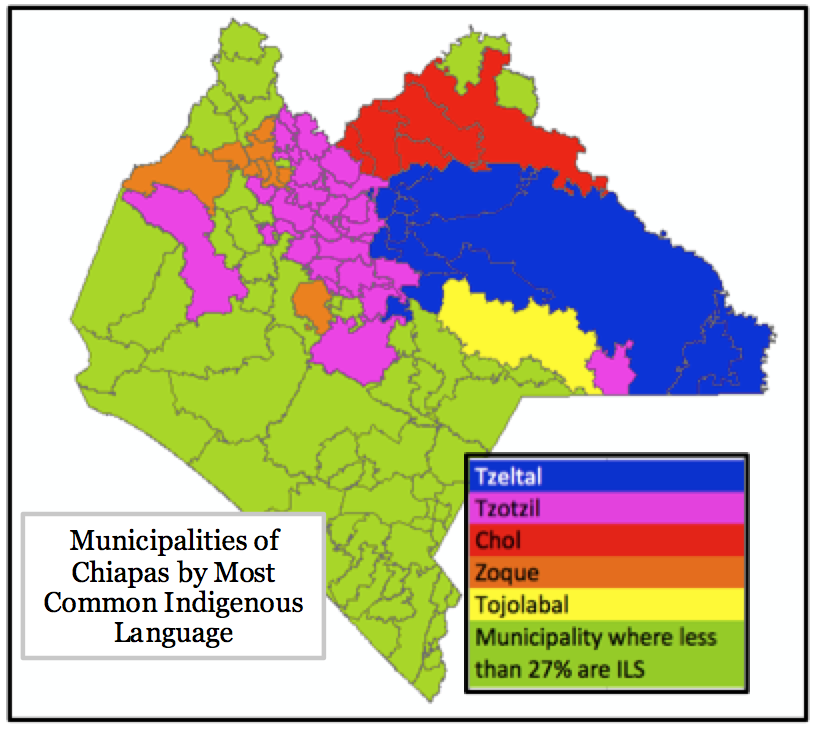

In Chiapas, however, indigenous languages have shown remarkable persistence. Over one million Chiapans, 27 percent, speak an indigenous language, up from 26 percent in 1990. Most notably, 34 percent of the state’s native language speakers are unable to speak Spanish, the highest rate of monolingualism in Mexico. Chiapas is home to five major languages: Tzeltal, Tzotzil, Chol, Tojolabal, and Zoque. The map below shows the most common language in each municipality.[2]

Though not Mexico’s largest indigenous languages—Náhuatl, Maya, and Mixteco have the most total speakers—Chiapas’ Amerindian tongues stand apart on key indicators of vitality including monolingualism, growth rate, home usage, and geographical permanence. In a chapter for Margarita Hidalgo’s Mexican Indigenous Languages at the Dawn of the Twenty-First Century, Barbara Cifuentes and José Luis Moctezuma used data on these indicators from the 2000 Census to sort 27 native languages into three categories of vitality. Tzeltal, Tzotzil, Chol, and Tolojabal were all placed in the highest category.[vii]

The Plight of Chiapas

While Chiapas’ indigenous languages remain vibrant, those who speak them are among the poorest in Mexico. Chiapas’ has the lowest GDP per capita and slowest growing economy of any Mexican state.[viii] Conditions for indigenous speakers are worse still. The average income per capita in indigenous municipalities[3] is just $3,314 USD,[ix] a third of the statewide figure and comparable to that of the Ivory Coast.[x] Also, indigenous municipalities’ average human development index, which combines measures of income, health, and education, is on par with that of Pakistan.[xi] This evidence does not prove a causal relationship between indigenous language usage and underdevelopment. Instead, both phenomena may be linked by a series of underlying factors that sustain each.

Factors Sustaining Underdevelopment

To raise incomes and promote development, Chiapas must address alarming deficits in education, gender equality, and urbanization.

In education, Chiapas’ indigenous youth trail behind their non-indigenous peers. In 2010, just 72 percent of 20 to 24-year-olds living in indigenous municipalities had completed primary school compared to 85 percent of those in the remaining municipalities. But education has improved. In 1990 just 31 percent of indigenous 20 to 24-years-olds had completed primary school.

Expanding education is vital for economic advancement. According to researchers at the Harvard Center of International Development, holding other variables constant, one additional year of education correlates with an 11.3 percent increase in income.[xii] But much of these gains only come with a university degree. Chiapas’ short-run return on staying in school is the lowest in Mexico, with those finishing the equivalent of high-school earning just 7.5 percent more than those completing primary education.[xiii]

Another problem facing indigenous communities is gender inequality. Indigenous female school attendance is 6.3 percentage points less than male attendance, a gap twice that which exists in Chiapas’ overall population.[xiv] One consequence is that only 73 percent of young female indigenous language speakers report Spanish-speaking ability, well below the figure for young men. Lastly, at around 20 percent, Chiapas has the lowest rate of female labor force participation in all of Mexico.[xv] A paucity of women in the workplace is not unique to the state’s indigenous communities and can be explained by a general lack of salaried positions, particularly in rural areas.[xvi]

Fortunately, education for indigenous females is expanding rapidly. Since 2000, the percentage of young women in indigenous municipalities who have received at least a primary school education rose from 41 to 74 percent.[xvii] This increase is not just significant as a matter of human rights. Promoting gender equality can help unlock a community’s full economic and social potential. For households, adding a second breadwinner supplements existing income. But improving women’s education is also an investment in future generations. Educated mothers improve the conditions of early-life development and are more active in their child’s schooling.

A final hindrance for indigenous Chiapans is an aversion to migration. Only a small percentage of Tzeltal and Tzotzil speakers live outside of the state and just 7 percent of the state’s indigenous language speakers reside in one of the four largest cities that are home to a quarter of the total population. Although, census data often fails to register temporary migrants and does not account for the sizeable exodus to the United States, Chiapas has definitely experienced far less migration than its neighbors, who also have large indigenous populations.

The unwillingness or inability of Chiapas’ indigenous speakers to move forms a barrier to economic advancement. Remittances from migrant relatives are an important component in a Mexican family’s household income.[xviii] Furthermore, there are significant wage disparities across the nation and even within the state of Chiapas that migrants could take advantage of. For instance, income per capita in the city of San Cristobal de Las Casas is four times that of the average indigenous community.

Yet, Chiapas remains the only state in the country in which the majority of citizens reside in rural localities. According to researchers on the Harvard Chiapas Project, “services and public transfers…help sustain rural communities [whose residents] would otherwise be obligated to move to urban centers.” At the same time, however, these academics acknowledge that, despite higher wages, urban areas currently lack “sufficient opportunities to induce migration.”[xix]

The Effect of Development on Indigenous Languages

Addressing poor education, gender inequality, and rootedness will likely weaken Chiapas’ indigenous languages.

In a 1990 study, University of Minnesota professors Robert McCaa and Heather Mills found that almost 100 percent of indigenous Chiapan children who attend school become bilingual in Spanish.[xx] Bilingualism in one generation often leads to language loss in the next. In a 2010 paper, Hirotoshi Yoshioka of the University of Texas demonstrated that children of bilingual primary school graduates are significantly less likely to retain the indigenous language than those of monolingual uneducated parents.[xxi]

Promoting gender equality in educational attainment and workforce participation could be equally detrimental to native languages. McCaa and Mills find that, regardless of schooling, 25 percent of indigenous children with a bilingual mother lose their indigenous language abilities.[xxii] The next generation of indigenous mothers will be far more bilingual than previous ones, making it likely that the first words their children hear are of Spanish, rather than of Mayan origin.

But migration has the potential to be most damaging to indigenous languages. According to the 2010 census, over 90 percent of Tzotsil and Tzeltal speakers living outside Chiapas are bilingual. Some of this is self-selection but not all. Holding a number of variables constant, Yoshioka found that indigenous children growing up in urban centers were three times less likely to retain their native language than their rural peers.[xxiii]

A Plan for Inclusive Development

However, in expanding education, fighting for women’s rights, and encouraging urbanization, Chiapas need not sacrifice its native languages to history. Smart policies could reduce language loss and preserve Amerindian tongues for generations to come.

A good start would be to increase the autonomy of indigenous communities, one of the principle demands of the Zapatista movement. In Chiapas, decisions concerning education, social welfare, infrastructure, and land usage are too often made by the state or federal government with little input from indigenous groups.[xxiv] The exclusion of native language speakers from the political process is evident in the fact that the Chiapan state constitution was only translated into the major indigenous languages this year.[xxv] Such marginalization has a history of ending poorly. In July, indigenous protesters killed the mayor of San Juan de Chamula who claimed to lack money for promised projects.[xxvi] Greater autonomy for indigenous groups would allow them to manage their own development. They could collect and allocate resources to the projects they deem most important, while courting potential business investors on their own terms.

Bilingual education is one area in which the devolution of power would help to preserve indigenous languages. Many teachers within indigenous communities are state-hired Spanish speakers who cannot provide a genuine bilingual environment. Furthermore, most schools lack texts written in indigenous languages, ensuring that advanced subjects are only taught in Spanish.[xxvii] With greater autonomy, communities could hire indigenous teachers, construct schools within their own villages, and obtain native language texts. In regard to this last initiative, the state government could also play an active role in the translation and publication of subject material and classic literature in indigenous languages. These measures would allow Chiapan students to stay in school longer (through high school) while keeping indigenous languages strong.

State and local governments should also support native language speakers who move to urban areas. Insufficient bilingual services make it difficult for such migrants to access public goods and navigate government bureaucracy. Furthermore, widespread discrimination contributes to a hostile environment in which indigenous people often shy away from using their native language. More could be done to recognize and celebrate indigenous languages within urban environments. Policies that ensure bilingual services, fight discrimination in the workplace and classroom, and strengthen urban indigenous communities might stem the language loss correlated with migration.

Conclusion

It would be unreasonable to expect that further development in Chiapas will have no effect on indigenous languages. Education, gender equality, and migration all work against the recent pattern of language stability. But policies that increase the autonomy of indigenous communities and fight the stigma associated with urban migration could allow indigenous speakers to advance socially and economically without having to abandon their native tongues. If done right, indigenous languages can be preserved throughout the 21st century and Chiapas will avoid the type of violent pushbacks that have characterized its recent history.

By Jordan Bazak, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Original research on Latin America by COHA. Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to LatinNews.com and Rights Action.

Featured image: Palenque, Chiapas. Taken from Flickr.

[1] All data, unless otherwise cited, comes from Mexico’s census bureau, the National Institute of Statistics, Geography, and Information (INEGI). Tables are available for download at the following link (http://www.beta.inegi.org.mx/proyectos/ccpv/2010/).

[2] This map was inspired by La Población Hablante de Lengua Indígena de Chiapas, a report released by the Mexican Census Bureau (INEGI) in 2004 using 2000 Census Data. The original can be found on page 7 here (http://docplayer.es/14571822-La-poblacion-hablante-de-lengua-indigena-de-chiapas.html). Using ArcGIS and data from the 2010 census, I construct an updated version.

[3] Indigenous municipalities are defined as municipalities in which over 50 percent of the population reported speaking an indigenous language in the given census year. This sample has remained remarkably consistent over the past two decades with somewhere between 30 and 35 municipalities depending on the Census.

[i] Will Grant, “Struggling on: Zapatistas 20 years after the uprising,” BBC, January 4, 2014. Accessed September 1, 2016. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-25550654.

[ii] Isaín Mandujano, “Thousands of Chiapas teachers initiate a strike,” Chiapas Support Committee, May 16, 2016. Accessed September 1, 2016. https://chiapas-support.org/2016/05/16/thousands-of-chiapas-teachers-initiate-a-strike/

[iii] Greg Campbell, “The NAFTA War,” Center for the Advancement of Journalism, July 29, 1996. Accessed September 1, 2016. http://www.tc.umn.edu/~fayxx001/text/naftawar.html

[iv] Jacobo García, “La reforma educative no sabe zapateco,” El País (Madrid), July 2, 2016. Accessed September 1, 2016. http://internacional.elpais.com/internacional/2016/07/02/mexico/1467464314_537564.html

[v] Ley General de Derechos Lingüísticos de los Pueblos Indígenas, Diario Oficial de la Federación, March 13, 2003. Accessed September 1, 2016. http://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/text.jsp?file_id=220917

[vi] XIII Censo General de Población y Vivienda 2000, Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). October 7, 2016.

[vii] Bárbara Cifuente and José Luis Moctezuma, “The Mexican indigenous languages and the national censuses: 1970-2000,” in Mexican Indigenous Languages at the

Dawn of the Twenty-First Century, ed. Margarita Hidalgo (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2006), 191-248.

[viii] Ricardo Hausmann, Timothy Cheston, y Miguel Angel Santos, “La Complejidad Económica de Chiapas: Análisis de Capacidades y Posibilidades de Diversificación Productiva.” (CID WP No. 303, Harvard University, 2015), accessed August 16, 2016, http://growthlab.cid.harvard.edu/chiapas-project.

[ix] “Índice de Desarrollo Humano Municipal en México,” Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo en México, March 27, 2014. Accessed October 10, 2016. http://www.mx.undp.org/content/mexico/es/home/library/poverty/idh-municipal-en-mexico–nueva-metodologia.html

[x] “Country Comparison: GDP – Per Capita (PPP),” CIA Worldbook, 2015. Accessed October 10, 2016. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2004rank.html

[xi] “Índice de Desarrollo Humano Municipal en México,” Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo en México, March 27, 2014. Accessed October 10, 2016. http://www.mx.undp.org/content/mexico/es/home/library/poverty/idh-municipal-en-mexico–nueva-metodologia.html

[xii] Dan Levy et al., “¿Por qué Chiapas es Pobre?” (CID WP No. 300, Harvard University, 2016), accessed August 16, 2016, http://growthlab.cid.harvard.edu/chiapas-project.

[xiii] “Salario relativo por hora de los trabajadores según nivel de escolaridad (2009),” in Panorama Educativo de México, Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación, 324. Accessed October 10, 2016. http://www.inee.edu.mx/bie/mapa_indica/2010/PanoramaEducativoDeMexico/RE/RE02/2010_RE02__c-vinculo.pdf

[xiv] “Polación Hablante de Lenguas Indigenas,” Instituto Naciónal de Estadística, Geografía, e Informática (INEGI), 2004.

[xv] Ricardo Hausmann, Timothy Cheston, y Miguel Angel Santos, “La Complejidad Económica de Chiapas: Análisis de Capacidades y Posibilidades de Diversificación Productiva.” (CID WP No. 303, Harvard University, 2015), accessed August 16, 2016, http://growthlab.cid.harvard.edu/chiapas-project.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] “Chiapas, Educación, ” XII Censo General de Población y Vivienda 2000, Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). September 14, 2016.

[xviii] Dan Levy et al., “¿Por qué Chiapas es Pobre?” (CID WP No. 300, Harvard University, 2016), accessed August 16, 2016, http://growthlab.cid.harvard.edu/chiapas-project.

[xix] Ricardo Hausmann, Timothy Cheston, y Miguel Angel Santos, “La Complejidad Económica de Chiapas: Análisis de Capacidades y Posibilidades de Diversificación Productiva.” (CID WP No. 303, Harvard University, 2015), accessed August 16, 2016, http://growthlab.cid.harvard.edu/chiapas-project.

[xx] Robert McCaa and Heather M. Mills, “Is education destroying indigenous languages in Chiapas?” Department of History, University of Minnesota, July 6, 1998. Accessed October 10, 2016. http://users.pop.umn.edu/~rmccaa/chsind/index0.htm

[xxi] Hirotoshi Yoshioka, “Indigenous language usage and maintenance patterns among indigenous people in the era of neoliberal multiculturalism in Mexico and Guatemala,” Latin American Research Review, 45.3 (2010): 5-35

[xxii] Robert McCaa and Heather M. Mills, “Is education destroying indigenous languages in Chiapas?” Department of History, University of Minnesota, July 6, 1998. Accessed October 10, 2016. http://users.pop.umn.edu/~rmccaa/chsind/index0.htm

[xxiii] Hirotoshi Yoshioka, “Indigenous language usage and maintenance patterns among indigenous people in the era of neoliberal multiculturalism in Mexico and Guatemala,” Latin American Research Review, 45.3 (2010): 5-35

[xxiv] Carolyn Gallaher. Interview with Author. Personal Interview. Washington D.C., September 28, 2016.

[xxv] “Traducen a lenguas indígenas Constitución en Chiapas,” El Universal (Mexico), August 17, 2016. Accessed August 27, 2016

http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/articulo/estados/2016/08/17/traducen-lenguas-indigenas-constitucion-en-chiapas

[xxvi] Jacobo Garcia, “Detenidas seis personas por la muerte del alcalde de Chamula y cuatro vecinos,” El País, July 23, 2016. Accessed October 11, 2016. http://internacional.elpais.com/internacional/2016/07/23/mexico/1469299157_344650.html

[xxvii] Carolyn Gallaher. Interview with Author. Personal Interview. Washington D.C., September 28, 2016.