Tackling Violence in Guatemala City through Equal Access to Education and Employment

Violence in Guatemala City is not news. When you live here, you get used to the fact that having drinks with friends will involve some recounting of stultifying personal experiences and close calls with armed thugs. Robbed recently by three young men, I myself became one of the 333 people whose cell phones are stolen on a daily basis in Guatemala with more than 142,000 stolen in 2012 alone. [1] As we share our tales of woe together, we ask ourselves: How can we put a stop to crime and violence in Guatemala City? In a previous COHA article, I proposed that coping with the local crime wave might begin with promoting equal access to quality education. Two years later, I believe that we may have to go further than education alone, although it is still an important factor. The overriding issue in the country is the persistent economic and social inequality of society. Guatemala is the 13th most unequal country in the world and 2nd most in Latin America. The top 10 percent of the Guatemalan elite control 55 times more resources than the bottom 10 percent of their fellow countrymen living in poverty. [2] As a result, a limited few have had access to quality education and formal employment opportunities. Improving the public education system and creating formal job opportunities are crucial antecedents for decreasing the rampant violence in Guatemala City.

Poor Quality in the Education System

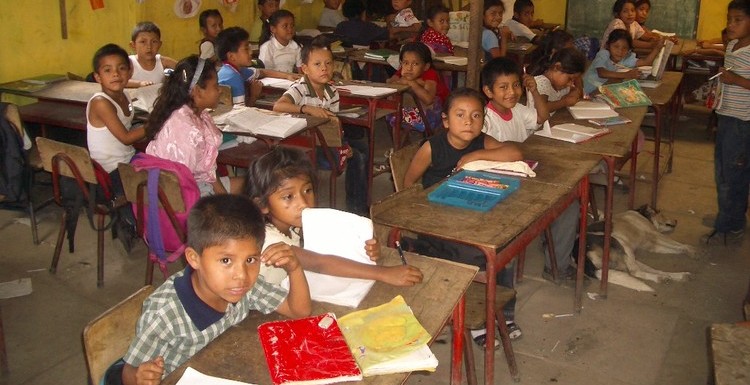

Guatemalan students in public schools receive a substandard education, especially when compared to those who attend private institutions. Public school teachers in general are unprepared to lead classes. According to a January study by Empresarios por la Educación, “teachers are not graduating with the knowledge, competencies, or skills necessary in the classroom.” [3] In Latin America, the vast majority of teachers are required to have between two and four years of higher education. The proposed education reform that is currently under scrutiny raises the amount of time teachers study by two years with the goal of better equipping teachers with knowledge to effectively structure and lead classes. However, this reform has been met with tremendous resistance by educators.

All this being said, Guatemala has over 200,000 high school graduates every year, with higher rates of students in secondary school than in years past. Compared to an average of 8.3 years of education in Latin America, Guatemala remains behind the curve with the average adult studying for just 5.5 years. For this reason, many of these graduates are the first to successfully complete high school in their families. In the inner-city community where I work, one out of every three adults never attended school and, of those who have entered, the vast majority only completed 4th grade. [4] For these families and others throughout Guatemala, seeing a son or daughter graduate from high school is an extremely powerful and hopeful moment. These graduates, however, meet with formidable challenges in finding formal employment.

Opportunities for Graduates

With more and more graduates each year, the country is struggling to generate even 20,000 jobs annually, meaning that only 12.5 percent of high school graduates are successful in finding formal employment. [5] On a national level, only one out of four Guatemalans are formally employed, meaning they have a formal schedule and receive at least minimum wage. [6] The capital city, where so many from the countryside hope to find jobs, presents even bleaker prospects, with the highest unemployment rate in the country. [7] Nearly one out of two individuals living in Guatemala City works informally. [8] Many arrive, determined and hopeful, to Guatemala City from distant towns and villages, only to scramble, searching for work in a dangerous city. As their personal situations become desperate, many families have no other alternative but to send their children to work. In Guatemala City, 6.9 percent of the urban labor force consists of children under 16 years of age. [9]

In addition to a struggling education system and lack of formal employment opportunities, urban youth must be seen as being extremely at risk due to the abundance of violence and a saturation of crime. Measuring crime rates across the country, 35 percent of violent and criminal activity occurs in and around Guatemala City. Living in the city as a young person, from 18 to 26 years of age, means that a person is 40 percent more likely to be a victim of a crime. Many hardworking young people find their paychecks snatched away by armed thugs, typically of their same age. According to the same study, 70 percent of criminal activity is committed by youth aged 18 to 26. Young people are therefore not only at risk for becoming victims of violence, but also of falling into a life of crime. For these reasons, the expectations of Guatemalan youth for their future, ranked 19 out of 20 youth populations surveyed in Latin America, demonstrating that few really have confidence that they have bright futures ahead. [10]

Lack of Opportunities Breeds Violence

In “red zones,” urban areas that have high rates of violent crime, a vicious cycle of violence and desperation is perpetuated. Young people in these areas who successfully complete high school are met with incredible resistance as they search for employment. Many companies and organizations here see a certain zone listed, or note a lack of a formal address and toss away applications, fearing the worst. These professionals and recruiters have only heard about the violence and crime to be found in the zones listed. Furthermore, these applicants typically don’t have flashy resumes – graduation from public institutions, basic English, and few previous employment experiences in comparison with applicants from “better areas,” whose parents have been able to provide them with private bi-lingual education and connect them to internships, allowing them to take full advantage of professional experiences. Students graduating from public institutions do not have the same professional “toolkit” as those who have attended the more prestigious private colegios.

The lack of opportunities for these at-risk youth is extremely challenging for them and for their families. Imagine the frustration of a mother working 12 hours a day, six days a week, to make sure that her oldest son has all the necessary notebooks and materials required by the public school. She waits anxiously for his high school graduation, hoping that soon she can cut back on her working hours and spend a little more time with the younger siblings in the house. Weeks and months pass after high school graduation, as her son frantically fills out job applications, waiting for a call back, for an interview, for a sliver of hope. Anxiety and pressure builds until a decision must be made in the household between feeding the household and the dream of formal employment. This young man, as many others, then has to decide between menial labor, with low risk but meager pay, and a life of crime, with high payoff but also high personal risk. Looking at these individual cases provides support for the argument made by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP or PNUD in Spanish) that one of the key causes of violence in Guatemala is social exclusion and inequality. [11]

A report released by the UNDP titled, “Statistical Report on the Violence in Guatemala” claims that inequality, coupled with a high rate of poverty, creates social tension and leads to violence and crime. Furthermore, with few social services available for the underprivileged, there is little formal support for people encountering dire circumstances. In many cases, non-profit organizations are trying to fill the gap in necessary programs, services ostensibly within the purview of the state, by offering education, medical attention, and support for victims of violence, among others. The lack of oversight by the government in regards to education and job creation has taken a toll.

The Cost of Violence

According to the same UNDP study, the trauma experienced by the vast majority of Guatemalans as a result of the high rates of crime and violence interferes with their ability to lead professionally and socially fulfilling lives. Many Guatemalans must weigh over the decision to leave the safety of their homes to attend a lecture or social event. Both the actual experience of an assault and the lingering fear that follows can be factors that distract from achieving professional and personal goals. Furthermore, the pain and suffering of friends and families when they lose a loved one to violence is immense. Their pain, coupled with the knowledge that it’s a near certainty that the assailant will not be brought to justice, creates incredible frustration and a sense of helplessness.

The actual cost of violence in Guatemala surpasses $2.3 billion USD (Q17 billion). [12] This huge amount of potential capital lost is a result of several factors. First, Guatemalan business owners are forced to spend nearly 12 percent of their overhead costs in security guards and surveillance systems, decreasing the amount of money available to be earned by the company and reducing the government’s taxable profit. [13] Additionally, money allotted for public healthcare, especially preventative health, must be redirected to emergency situations. Gravely ill patients have found themselves waiting for hours in public hospitals because gunshot victims must take priority. Saving these victims requires the public hospitals to provide expensive surgeries.

Another heavy toll taken by crime and violence in Guatemala is a dramatic drop in investment and tourism. According to the study, ¨The Economic Costs of Violence in Guatemala,¨ the country, on account of the violence, loses $46.6 million USD each year of possible income from private investors and $474.2 million USD from its potential income in the tourism industry. [14] National and foreign investors are hesitant to invest in a country with high rates of crime, steep security costs, and rampant corruption. With daily reports of shootings dominating national and international media, potential tourists shy away from Guatemala. And, for those who make the trip, many arrive and quickly flee what they discover to be the notoriously dangerous capital city towards Antigua or other slightly more tourist-friendly centers. Guatemalan leaders must focus on lowering the crime rate and improving the image of the city if they hopes to reverse this downward spiral. Foreign investment and tourism is crucial for generating necessary employment opportunities.

Connections for a better Guatemala

The Guatemalan government, local business owners, and non-profit organizations can reverse this negative trend by partnering together. In terms of education, the government must do its part in better preparing teachers to lead classes in public institutions. Public and private schools must connect in order to share best practices on education so that the entire education system evolves and all of the nation’s students benefit. In addition, non-profit organizations focused on education could help promote this dialogue. Only by sharing experiences and techniques between public, private, and non-profit institutions can the education system truly support all students.

The Guatemalan government must promote reliable professional skills development within the classroom to prepare students for a productive life after graduation. Currently, many students are required to participate in an internship during the month of September before graduation. However, there is very little oversight on the school’s part about preparing these young adults for the next stage of their careers. Promoting training on interpersonal and professional skills beforehand is essential for students to feel comfortable during their internship and to be able to take full advantage of the opportunity being offered to them. Students also need to understand that an internship is a valuable way to develop their personal professional network.

Many students from underprivileged backgrounds have few professional contacts upon leaving college, as their parents and neighbors are not themselves often formally employed. As a result, the professional networks of these youths can be limited. In a country where 80 percent of jobs are secured with the help of a relative or friend, it is imperative that at-risk youth are exposed to new contacts. Non-profit organizations and public schools must therefore partner with large companies and organizations in order to promote this type of exposure for students. Employees of these companies can model and reinforce professionalism for students who do not have professional role models at home.

Finally, the government must work with local and international businesses to promote the development of formal employment opportunities. With so many Guatemalans working in the informal economy, the government is losing large sums of valuable tax dollars. In addition, it is imperative to address the security issue while promoting foreign investment and tourism. If public and private schools, together with NGOs, are working in concert to prepare students, the government must do its part in developing job opportunities for these youths. Only with proper preparation and opportunities will youth be able to make an honest living.

For Guatemala to address the situation at hand, everyone must work together to academically and professionally prepare young adults to enter the workforce where they find viable employment opportunities. Unemployed and dissatisfied youth continue to represent a great risk for criminal activity. Transnational and local gangs provide perilous landing places for many of these frustrated young adults. Just recently a violent territory battle between two rival gangs left eleven people dead and fifteen people injured. Only by providing equal access to education and employment opportunities can Guatemala begin to curb the dangerous outbreak of violence that has left 6,000 people dead this year alone. [15] Both the steady earnings and positive self-esteem generated from being formally employed will help channel the vital energy of youth into the workforce, rather than into a career of criminal activity.

Megan McAdams, Research Fellow at the Council Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated.

For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action

References

[1] Omar Archila “Reportan 333 celulares robados por día” ElPeriodico.com, July 26, 2013. Accessed September 2, 2013. http://www.elperiodico.com.gt/es/20130726/pais/231713/

[2] Baldizión, Manuel. “Pobreza o Desiguldad.” El Periódico. September 16, 2013. Accessed September 16, 2013. http://www.elperiodico.com.gt/es//pais/21881

[3] Empresarios por la Educación “¿Como estamos en Educación?” Report by Empresarios por la Educación. January, 2013. Accessed August 30.

[4] Safe Passage. “Statistics and Results – Census of the Community of Safe Passage 2013” Census and Analysis by Safe Passage staff. January 8, 2013. Accessed August 30.

[5] Dionisio Gutierrez “Modelo de Desarrollo” from Dimensión con Dionisio Gutierrez. January 25, 2013. Accessed August 30. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uJcII1jgtBI

[6] Instituto Nacional de Etadisticas. “2012 Encuesta Nacional de Estadisticas e Ingreso” National Census. Accessed August 30, 2013. www.ine.gob.gt.

[7] Dionisio Gutierrez “Modelo de Desarrollo” from Dimensión con Dionisio Gutierrez. January 25, 2013. Accessed August 30, 2013. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uJcII1jgtBI.

[8] Instituto Nacional de Etadisticas. “2012 Encuesta Nacional de Estadisticas e Ingreso” National Census. Accessed August 30, 2013. www.ine.gob.gt.

[9] Instituto Nacional de Etadisticas. “2012 Encuesta Nacional de Estadisticas e Ingreso” National Census. Accessed August 30, 2013. www.ine.gob.gt.

[10] United Nations Development Program “Primera Encuesta Iberamericano de la Juventud” July 22, 2013. Accessed August 30, 2013. http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/Democratic%20Governance/Spanish/PNUD_Encuesta%20

Iberoamericana%20de%20Juventudes_%20El%20Futuro%20Ya%20Llego_Julio2013.pdf

[11]United Nations Development Program “Informe estadístico de la violencia en Guatemala” UNDP. December, 2007. Accessed August 30, 2013. http://www.undp.org.gt/data/publicacion/Informe%20Estad%C3%ADstico%20de%20la%20Violencia%20en

%20Guatemala%20final.pdf

[12] United Nations Development Program “Informe estadístico de la violencia en Guatemala” UNDP. December, 2007. Accessed August 30, 2013. http://www.undp.org.gt/data/publicacion/Informe%20Estad%C3%ADstico%20de%20la%20Violencia%20en

%20Guatemala%20final.pdf

[13] Julio Santos “Empresarios gastan 12% de sus costos en seguridad” Siglo21.com. Accessed August 30, 2013.

[14] United Nations Development Program “El Costo Economico de La Violencia en Guatemala” Georgetown.edu. January 2006. Accessed August 30. http://pdba.georgetown.edu/Security/citizensecurity/guatemala/presupuestos/EstudioCostodeViolencia.pdf

[15] Agence France Presse “Guatemala Liquor Store Standoff: 11 killed, 15 wounded In Gun Violence” HuffingtonPost.com. September 8, 2013. Accessed September 9, 2013.