Students Change Political Debate Leading Up to Chilean Primary Elections

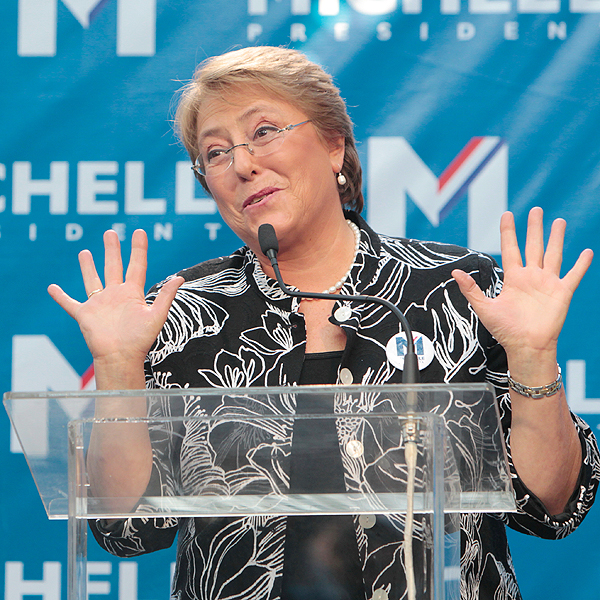

Chile’s education system has generated fiery controversy and political discourse since student protests first appeared in 2006 during former President Michelle Bachelet’s tenure (2006-2010). [1] After minimal and half-hearted improvements, frustration with the political system has intensified and protests persist. However, Bachelet has decided to compete for a second presidential term after returning from her Executive Director position at the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women in New York. Her campaign highlights education reform as part of her larger platform that aims to address social and economic inequality in her home country. Unlike her fellow candidates, Bachelet has put forward specific policy proposals to change the broken system, which provide hope but no guarantees for substantive change.

Photo Source: El Mercurio

The current Chilean education system exacerbates existing inequality. The country’s Gini coefficient (which measures income distribution) stands at 0.49 (on a scale of 0 to 1), the highest of all members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). [2] In addition, the gap between the average university tuition and the average income per person in Chile is the largest among OECD countries, partially because the majority of Chilean universities are private. [3] Further compounding the problem, universities are heavily concentrated in metropolitan areas, creating geographic and monetary barriers for students. Aspiring college students that are not from major university cities such as Santiago and Concepción may need to move or commute to receive higher education, raising the price of attending these institutions, reducing time available for studying, and encouraging further urbanization.

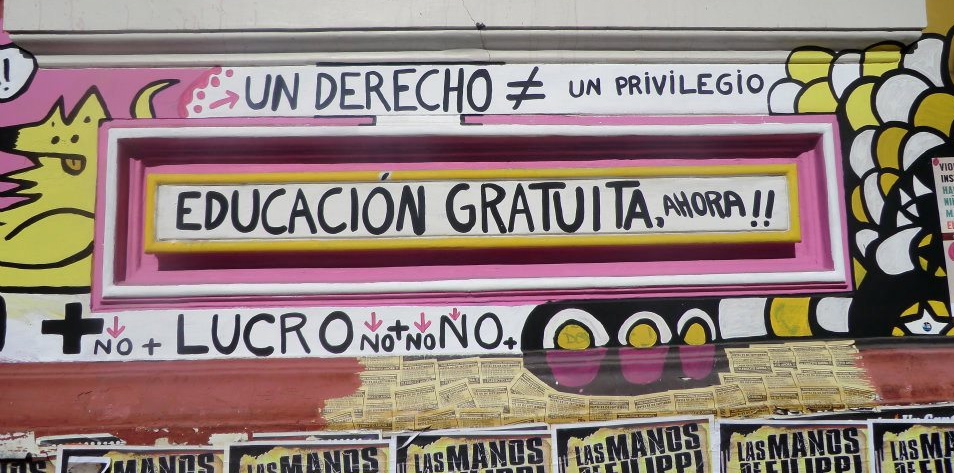

Photo Source: Jessie Durrett

In hopes of bringing about transformational change, students demand free, quality education. They also reject the profitmaking nature of universities. [4] Chilean law already prohibits treating education as a business venture, but the education sector has become increasingly lucrative, especially because it is the sector most heavily intertwined with the financial lending industry. [5] On June 26, in the lead up to primary elections on June 30, the nationwide protests became violent after hooded protestors threw Molotov cocktails and police responded with water cannons and tear gas. Students were also occupying schools that will function as voting centers to intensify their call to action, but were evicted by government authorities Thursday morning. [6]

Photo Source: La Prensa

Polls show that about 70 percent of the nation supports the demands of student protestors, ensuring that their concerns will influence the primary elections. [7] Candidates of the Nueva Mayoría (New Majority) primary (who represent opposition parties of center, left, and center-left political affiliations) advocate various means of improving quality and access. Bachelet, the likely winner of the primary, has put forward the most concrete plan for education reform, promising to directing 1.5 to 2 percent of GDP to making education free and universal through university-level in six years. [8] Bachelet’s proposal also includes increasing the number of public universities, specifically in smaller cities facing economic challenges like Rancagua and Aysén. [9]

José Antonio Gómez of the Social Democrat Radical Party (Partido Radical Social Demócrata), Claudio Orrego of the Christian Democrat Party (Partido Demócrata Cristiano), and Independent Andrés Velasco are also competing in the Nueva Mayoría June 30 primary, but their plans for education reform glaringly lack particulars. While Gómez supports free universal education and repeats the protestor’s chant “publica, gratuita, y de calidad” (public, free, and quality), Orrego favors state-funded education for the 70 percent of the population that is most in need, and Velasco argues for gradual changes that eventually would fund education for those who cannot pay. [10] On June 23, during the final Nueva Mayoría debate before the primary elections, Gómez favored state-controlled education and more training for teachers, but Bachelet’s proposal remains the most detailed by far. [11]

Photo Source: United Photographers International

The front-runner of the right-wing coalition Alianza por Chile (Alliance for Chile), Andrés Allamand, strongly opposes Bachelet’s position, arguing that ending subsidized private education affects the liberty to teach, the right of parents to choose their children’s schools, and the middle class’ ability to access quality education. His stance aligns with that of current President Sebastián Piñera. [12]

Marco Enríquez-Ominami is also running for president but is not taking part in the primaries. He will run in the November general election as the Progressive Party’s (Partido Progresista) candidate. Enríquez-Ominami has suggested a number of ways to transform the existing education system to ensure accessibility and quality, but maintains that he would work through a democratic process to find a solution that fits the country’s needs.

Analysis of the political aspects of Bachelet’s proposal sheds light on election dynamics, but at the moment no one can predict the outcomes for the upcoming races or the future of education reform. Bachelet announced her education platform after the Communist Party of Chile agreed to support her candidacy, dependent on her willingness to push education reform and agree to a number of other political arrangements.

There are several factors that help Bachelet’s chances of passing major education reform if reelected. She left office in 2010 with an approval rating of 84 percent, higher than any departing president before her. [13] Since then, her international clout has amplified, and the vigorous student movement has kept education high on the political agenda.

Doubts about Bachelet’s sincerity and her ability to reform education in the current political climate are justified. Bachelet responded to student protests with little sympathy during her first term, and the country’s political machine favors elite voices and conservative policies. However, her concrete proposal suggests commitment to real change and Bachelet has the opportunity to further improve her odds. First, Bachelet can engage student leaders in the creation of her education policy to inform her coming proposals, enhance its credibility, and widen her political base. If possible, Bachelet should reach out to student leaders that bridge party lines to help ensure that education reform reflects the perspectives of people with various political affiliations. Second, Bachelet should continue to link education to her greater goal of reducing inequality in order to highlight the issue’s relevance to Chile’s long-term, sustainable development.

Students have made their voices heard, changing the discourse surrounding the upcoming elections. Of the presidential candidates competing in the June 30 primaries, Bachelet has most successfully integrated the demands of student activists into her campaign platform. She has been expected to win the Nueva Mayoría primary since campaigning began, but her competitors further hindered their chances by failing to produce explicit plans to address frustrations with the education system.

Jessie Durrett, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

1. Franklin, Jonathan. “Protests Paralyse Chile’s Education System.” The Guardian, June 6, 2006, sec. World news. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2006/jun/07/chile.schoolsworldwide.

2. Adams, Rosalind. “Chilean Presidential Candidate Pledges New Public Universities.” The Santiago Times, June 8, 2013. http://www.santiagotimes.cl/chile/education/26281-chilean-presidential-candidate-pledges-new-public-universities.

3. Benedikter, Roland, and Katja Siepmann. “Meet the Mattes.” Foreign Affairs, June 12, 2013. http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/139476/roland-benedikter-and-katja-siepmann/meet-the-mattes?page=2; “Bachelet Promete Educación Universitaria Gratuita Si Resulta Electa En Chile.” Diario Los Andes, June 7, 2013. http://www.losandes.com.ar/notas/2013/6/7/bachelet-promete-educacion-universitaria-gratuita-resulta-electa-chile-719231.asp.

4. “Piñera Llama a Los Estudiantes a Manifestarse Este Jueves Con Tranquilidad.” Lainformacion.com, June 12, 2013. http://noticias.lainformacion.com/educacion/ensenanza-y-aprendizaje/pinera-llama-a-los-estudiantes-a-manifestarse-este-jueves-con-tranquilidad_uWxPPKwSGcBmwHLAsbXW45/.

5. Benedikter, Roland, and Katja Siepmann. “Meet the Mattes.” Foreign Affairs, June 12, 2013. http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/139476/roland-benedikter-and-katja-siepmann/meet-the-mattes?page=2.

6.“Huge Chile Student Rally Turns Violent.” Press TV, June 28, 2013. http://www.presstv.ir/detail/2013/06/27/311031/huge-chile-student-rally-turns-violent/; Chumley, Cheryl. “Chile Police Storm Schools Taken over by Hundreds of Students.” The Washingtion Times, June 27, 2013. http://www.washingtontimes.

7. Foote, Jackson. “Students Detained, Wounded as Thousands March on Chilean Capital.” In These Times Blog – Uprising, March 29, 2013. http://inthesetimes.com/uprising/entry/14797/chile_student_protests_end_in_violence/.

8. “Bachelet Propone Universidad Gratis Para Todos Por Medio de Una Reforma Educativa Completa.” Noticias24. Accessed June 28, 2013. http://www.noticias24.com/internacionales/noticia/61488/bachelet-propone-universidad-gratis-para-todos-en-seis-anos/.

9. Adams, Rosalind. “Chilean Presidential Candidate Pledges New Public Universities.” The Santiago Times, June 8, 2013. http://www.santiagotimes.cl/chile/education/26281-chilean-presidential-candidate-pledges-new-public-universities.

10. “¿Educación Gratuita?: El Tema Que Abre El Debate de Los Candidatos de La Oposición.” El Vacanudo.cl, June 11, 2013. http://www.elvacanudo.cl/noticia/politica/educacion-gratuita-el-tema-que-abre-el-debate-de-los-candidatos-de-la-oposicion.

11. Riqueleme, Karen. “Chile Election Watch: Final Debates before Primary Elections.” I Love Chile News, June 24, 2013. http://www.ilovechile.cl/2013/06/24/chile-election-watch-final-debates-primary-elections/87948.

12. “Allamand: ‘Propuesta de Bachelet Es La Más Grave Amenaza Para La Libertad de Enseñanza’.” Nación.cl, June 15, 2013. http://www.lanacion.cl/noticias/site/artic/20130615/pags/20130615183644.html.

13. Chavarría, Paula Escobar. “In Chile, Departing President Michelle Bachelet Proved Women Can Lead.” The Washington Post, March 14, 2010, sec. Opinions. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/03/12/AR2010031201791.html.