Missed Connections: Mexican Government Falls Short on Continuing Education for U.S.-Raised Mexican Nationals

By Mariana Sánchez Ramírez, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF version of this article, click here.

While many commentators have questioned the Trump administration’s aggressive immigration policy, far fewer have covered the feeble effort of the Mexican education system to accommodate the re-integration of returning students, Los Estudiantes de Retorno, who were made to return to their country of origin. Given the broadening definition of “criminal alien” under the Trump administration, it is imperative that Mexico reform the nation’s education revalidation process while simultaneously incorporating bicultural education elements in the national curriculum in order to adequately embrace and serve the basic needs of its students.

The uncertainty surrounding mass deportations and the border wall continue to undermine U.S.-Mexico relations since the inauguration of U.S. President Donald Trump. Trump’s “Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States” executive order has broadened the definition of a “criminal alien” so much that it has almost single-handedly criminalized an estimated eleven million people residing in the United States without proper documentation.[i] A Department of Homeland Security (DHS) official clarified to the Washington Post that “anyone who had entered the United States illegally or overstayed or violated the terms of a visa” is now considered a criminal and subject to deportation at any given time.[ii]

The Uncertain Fate of American Children Who DREAM

Approximately 750,000 young undocumented immigrants are beneficiaries of the 2012 federal government, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program (DACA), a program that grants them two-year work permits and deportation relief for minors brought to the United States before the age of sixteen.[iii] Children who were brought into the United States, known as DREAMers, must meet a certain set of criteria to benefit from the DACA program in order to study and/or work in the United States. Undocumented immigrants requesting DACA must have been “under the age of 31 as of June 15, 2012, come to the United States before age 16, lived here for at least five years continuously, and attend or graduate from high school or college [or be an honorably discharged veteran of the United States military] and have [had] no criminal convictions.” [iv] [v] It is important to note that the DACA program does not provide permanent legal status or a pathway to U.S. citizenship, nor does it provide beneficiaries access to “federal welfare or student financial aid.” [vi]

The growing threat of mass deportations in the era of President Trump continues to generate anxiety for DACA recipients. They fear that the Trump administration will rescind the federal program and immediately place beneficiaries in deportation proceedings—in many cases to countries they have no recollection of living in.

On the campaign trail, Donald Trump vociferously opposed former President Obama’s executive orders on immigration. Presidential candidate Trump defined the creation, implementation, and expansion of federal programs created by the Obama administration as an “executive amnesty.” [vii] On June 23, 2016, President Trump tweeted “[t]he election, and the Supreme Court appointments that come with it will decide whether or not we have a border and, hence, a country. Meanwhile, [Hillary] Clinton has pledged to expand Obama’s executive amnesty, hurting poor African-American and Hispanic workers by giving away their jobs and federal resources to illegal immigrant labor — while making us all less safe.” The tweet demonstrates how quick candidate Trump was to define the undocumented immigrant community as a threat to America’s national security. Actions such as the infamous refugee ban and the expansion of the “criminal alien” definition clearly illustrate the salient nature of anti-immigrant sentiment early in his administration.

Uncertainty of Comprehensive Immigration Reform Triggered U.S.-Raised Mexicans to Return Home

Comprehensive immigration reform in the United States is unlikely as local, state, and federal government entities are unable to agree on whether or not to provide a permanent legal immigration status with a pathway to American citizenship for eleven million people residing in the United States without proper documentation. Border security is the primary factor in the partisan divide between the Republican and Democratic Party on immigration reform.[viii] A majority of Republicans believe that border security must be achieved prior to proposing legislation that “would allow undocumented immigrants to seek legal status.” [ix] On the other hand, a majority of Democrats believe that the issue of border security and legislative change in immigration law can occur in conjunction with each other. The uncertainty of comprehensive immigration reform placed a burden on undocumented students who were often barred from pursuing a college education and work in the United States.

Thus, prior to DACA, a large number of undocumented high school graduates viewed their homeland’s higher education system as a viable alternative to pursue and achieve their educational and professional goals. Known as the “Estudiantes de Retorno“ (the returning students), these young adults have spent the majority of their childhood living and attending public school in the United States but are now enrolled in the Mexican university system.[x] This growing demographic trend within Mexican universities has been driven by a series of socioeconomic factors in the United States: anti-immigrant legislation, a rising number of deportations, and the 2008 financial meltdown. [xi]

Such factors would seem to matter less for students receiving a K-12 education in the United States as the 1982 Plyler vs. Doe U.S. Supreme Court decision ensures free basic education for all students in the United States regardless of legal status.[xii] They do, however, significantly reduce access to higher education opportunities. The majority of this demographic who resided in the United States did not have the legal paperwork nor the financial solvency to start the college admission process.[xiii] Furthermore, state legislation in California and Arizona as well as federal legislation (Proposition 300, S.B. 1070, and H.R. 4437) partially succeeded in establishing legal and financial barriers to prevent the enrollment of undocumented high school graduates into private or public universities in the United States. Granted that “there is no federal or state law that prohibits the admission of undocumented immigrants to U.S. colleges”, access to higher education was nearly impossible for a majority of students in the United States as many states required “applicants to submit proof of citizenship or legal residency” to enroll in the state’s university system.[xiv] State and federal regulation effectively curtailed higher education access to this student group. Restrictive financial aid policies and in-state tuition requirements made access to American higher education financially unattainable to students without appropriate documentation.[xv]

Bureaucratic Complexities Mar Higher Education Access and Revalidation of Los Estudiantes de Retorno

Amidst the uncertainty surrounding the future of the DACA program, Mexico, the country of origin for 75% of DACA recipients, has recently taken various steps to help those students returning to their home country pursue higher education.[xvi] To validate certificates, diplomas, or other academic degrees earned abroad, Mexican students must submit a birth certificate, academic background, official transcripts, and a payment processing fee to the Ministry of Public Education. [xvii] Based on the paperwork, the Ministry of Public Education will grant official validity to certificates, diplomas, and academic degrees earned outside of the national education system, as long as these certifications are compatible with Mexican requirements.[xviii] [xix] As of July 2015, the ministry no longer required an “international apostille from the U.S. Secretary of State [and] official government translations” in order to certify the student’s studies.[xx] Obtaining this document was not feasible for many returning families, as the issuance of a U.S. State Department’s apostille became a stringent and inefficient process for Los Esudiantes de Retorno. Student’s endured a difficult, year-long process to access and request the necessary paperwork to fulfill the U.S. State Department’s apostille requirements from Mexico in order to transfer U.S. academic credits into the Mexican education system.[xxi] By stipulating an impossibly complicated requirement, the Mexican government indirectly infringed upon the student’s constitutional right to an education.

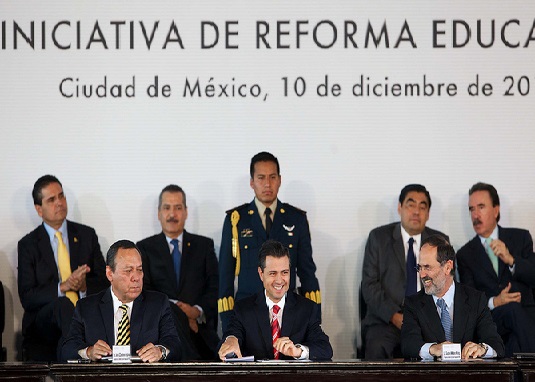

Dropping the apostille requirement was just the beginning. On February 1, President Enrique Peña Nieto introduced a preferential initiative to the Mexican Senate to reform the Ley General de Educación (General Education Act) in order to facilitate the “academic mobility” of Mexican children and young people who are currently studying or have completed their studies outside the country.[xxii] On March 2, the Mexican Senate approved a bill that allows education institutions to “validate foreign degrees and transcripts, something previously only allowed in private schools and specific public universities.” [xxiii] But while such measures are certainly welcome, for some students, they have arrived disappointingly late. According to the 2014 Census of Teachers, Schools, and Students, there were an estimated 487,000 Estudiantes de Retorno seeking to complete their studies in Mexican education institutions. [xxiv] The 2008 U.S. economic downturn, the threat or actuality of deportation, and access to higher education are arduous life events that have caused families to uproot their lives from the United States and return to Mexico. Yet, the resilience and perseverance students demonstrate in overcoming bureaucratic barriers to enroll and revalidate their studies in the Mexican education system is admirable as they aspire to fully re-integrate into Mexican society through its higher education system. Only now, amidst the uncertain future of the DACA program, has the Mexican government demonstrated a notable, yet still faint interest in eliminating the red tape that many feel have impaired the reintegration of students returning from abroad who see the Mexican higher education system and job market as a logical, viable alternative to pursuing their career goals. Mexico’s national education system has failed its citizens as many governmental institutions have not adequately funded or achieved a necessary level of reform in order to meet the needs of bilingual, bicultural students returning from the United States.

Acknowledging the Need for Bicultural Education in Mexico

In both the United States and Mexico, negligent legislation and excessive bureaucracy have characterized the educational experiences of Estudiantes de Retorno in both countries. The educational measures and newfound interest in reforming Mexico’s General Education Act are important, yet lethargic steps in ensuring equitable educational access. Upon their return to Mexico, not only do these students encounter excessive bureaucratic barriers but also a dismal bicultural education curriculum that jeopardizes their ability to pursue a college degree.

For students who return to Mexico to begin their college education, the Examen de Habilidades y Conocimientos Básicos (EXHCOBA) continues to be the greatest roadblock to meeting the minimum college admission requirements.[xxv] Similar to the SAT or ACT standardized tests in the United States, the EXHCOBA tests the applicant’s knowledge in the following areas: Spanish, quantitative and verbal abilities, social sciences, and mathematics.[xxvi] For students who completed K-12 education in the United States, a lack of effective Spanish language skills and Mexican historical knowledge is often detrimental to their admissions process in Mexico. [xxvii] Students cannot showcase their academic prowess because they simply do not have the support to transfer their skill set within the Mexican general education system. The entrance exam structure and questions illustrate how the Mexican education system undermines the value of the transnational experience of bicultural students who spent their formative years in the United States and have returned to Mexico. In its current form, the EXHCOBA does not accurately test nor measure how a student who has been enrolled in the United States will perform in a Mexican university. [xxviii]

On the other hand, research by Dr. Jill Anderson of the Wilson Center’s Mexico Institute concludes that 75 percent of a student’s undergraduate degree coursework completed abroad must align with “an accredited higher education institution in Mexico” in order to fully continue or revalidate their studies in their country of birth.[xxix] Ultimately, however, this is an unrealistic, inadequate standard for Mexican students who complete coursework in the United States. There is minimal correlation between the U.S. liberal arts education track and the licenciatura (“license to practice”) professional track prevalent in the Mexican university system.[xxx] “Diversity of subject matter” is the starkest dichotomy that exists between the liberal arts and licenciatura higher education models. Traditionally, the licenciatura is a specialized degree program that “prepares an individual for a specific profession” by incorporating coursework that only aligns with a student’s chosen field of interest. [xxxi] The liberal arts model encourages exploration as it requires students to complete General Education coursework outside of their major in order to “broaden their perspective” and pursue unique, unconventional career paths.[xxxii] The variant rules and regulation established by public and private universities in Mexico for students with non-traditional educational backgrounds like those of the Estudiantes de Retorno is yet another obstacle that returning students face when seeking access to higher education.[xxxiii] [xxxiv]

Conclusion

Educational access is essential in the societal re-integration of Los Estudiantes de Retorno. The students’ transnational educational experience in the United States and Mexico are an asset to the greater society. This demographic’s personal experiences foster a unique, even keen awareness of the social, economic, and political repercussions facing their local communities in the United States and Mexico. First and foremost, it is essential that Mexico’s Ministry of Public Education re-evaluate and modernize the national accreditation and curriculum standards in order to promote the continuation and recognition of the group’s university studies in Mexico. It is in the interest of the Mexican government to create and implement programs that reinforce the skill-sets of its students whose transnational education experience strengthens their awareness contributions as global citizens.

By Mariana Sánchez Ramírez, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Additional editorial support provided by Kirwin Shaffer, Senior Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs, Jordan Bazak, Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs, and Mitch Rogers and Kate Teran, Research Associates at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Featured image: Presentación de iniciativa de Reforma Educativa Taken from: Flickr

[i] Medina, Jennifer. “Trump’s Immigration Order Expands the Definition of ‘Criminal'” The New York Times. January 26, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/26/us/trump-immigration-deportation.html?_r=0.

[ii] Hauslohner, Abigail, and Sandhya Somashekhar. “Immigration authorities arrested 680 people in raids last week.” The Washington Post. February 13, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/immigration-authorities-arrested-680-people-in-raids-last-week/2017/02/13/3659da74-f232-11e6-8d72-263470bf0401_story.html?utm_term=.940fd2c18305.

[iii] Krogstad, Jens Manuel. “Unauthorized immigrants covered by DACA face uncertain future.” Pew Research Center. January 05, 2017. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/01/05/unauthorized-immigrants-covered-by-daca-face-uncertain-future/.

[iv] Marshall, Serena. “What Could Happen to DACA Recipients Under Donald Trump.” ABC News. November 16, 2016. http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/happen-daca-recipients-donald-trump/story?id=43546706.

[v] Pope, Nolan G. “The Effects of DACAmentation: The Impact of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals on Unauthorized Immigrants.” Journal of Public Economics 143. November 2016. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047272716301268

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] De Vogue, Ariane, and Tal Kopan. “Deadlocked Supreme Court deals big blow to Obama immigration plan.” CNN. June 23, 2016. http://www.cnn.com/2016/06/23/politics/immigration-supreme-court/.

[viii] Doherty, Carroll. “5 Facts about Republicans and immigration.” Pew Research Center. July 08, 2013. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/07/08/5-facts-about-republicans-and-immigration/.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Cortez Roman, Nolvia Ana, Arelys Karina Garcia Loya, and Adriana I. Altamirano Ruiz. “Estudiantes Migrantes De Retorno En México. Estrategias emprendidas para acceder a una educación universitaria.” Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa. June 25, 2015. http://www.redalyc.org/html/140/14042022008/.

[xi] Gonzalez Barrera, Ana. “More Mexicans Leaving Than Coming to the U.S.” Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project. November 19, 2015. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2015/11/19/more-mexicans-leaving-than-coming-to-the-u-s/.

[xii] “Public Education for Immigrant Students: Understanding Plyler v. Doe.” American Immigration Council. October 24, 2016. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/plyler-v-doe-public-education-immigrant-students.

[xiii] Cortez Roman, Nolvia Ana, Arelys Karina Garcia Loya, and Adriana I. Altamirano Ruiz. “Estudiantes Migrantes De Retorno En México. Estrategias emprendidas para acceder a una educación universitaria.” Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa. June 25, 2015. http://www.redalyc.org/html/140/14042022008/.

[xiv] “Advising Undocumented Students.” Advising Undocumented Students – Explaining Financial Aid | Education Professionals – The College Board. https://professionals.collegeboard.org/guidance/financial-aid/undocumented-students.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Krogstad, Jens Manuel. “Unauthorized immigrants covered by DACA face uncertain future.” Pew Research Center. January 05, 2017. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/01/05/unauthorized-immigrants-covered-by-daca-face-uncertain-future/.

[xvii] Secretaría de Educación Pública. “Información Para Revalidar Estudios Del Tipo Superior.”

http://www.ree.sep.gob.mx/work/models/sincree/Resource/archivo_pdf/triptico_revalidacion_DGAIR.pdf

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] Anderson, Jill. “Bilingual, Bicultural, Not Yet Binational: Undocumented Immigrant Youth in Mexico and the United States.” October 2016. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/bilingual_bicultural_not_yet_binational_undocumented_immigrant_youth_in_mexico_and_the_united_states.pdf

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] Jacobo, Mónica, and Nancy Landa. “La exclusión de los niños que retornan a México.” Nexos. August 1, 2015. Accessed March 28, 2017. http://www.nexos.com.mx/?p=25878#_ftn1.

[xxii] El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. “Senado mexicano aprueba revalidación de estudios de “dreamers” deportados por Trump.” El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. March 2, 2017. http://observatoriocolef.org/?noticias=senado-mexicano-aprueba-revalidacion-de-estudios-de-dreamers-deportados-por-trump.

[xxiii] Bernal, Rafael. “Mexico moves to recognize Dreamers’ US education.” The Hill. February 27, 2017. http://thehill.com/latino/321347-mexico-moves-to-recognize-dreamers-us-education.

[xxiv] Jacobo, Mónica, and Nancy Landa. “La exclusión de los niños que retornan a México.” Nexos. August 1, 2015. Accessed March 28, 2017. http://www.nexos.com.mx/?p=25878#_ftn1.

[xxv] Cortez Roman, Nolvia Ana, Arelys Karina Garcia Loya, and Adriana I. Altamirano Ruiz. “Estudiantes Migrantes De Retorno En México. Estrategias emprendidas para acceder a una educación universitaria.” Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa. June 25, 2015. http://www.redalyc.org/html/140/14042022008/.

[xxvi] Felipe, Tirado. “Validez predictiva del examen de habilidades y conocimientos básicos (EXHCOBA) Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa.” 1997. http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/140/14000305.pdf

[xxvii] Cortez Roman, Nolvia Ana, Arelys Karina Garcia Loya, and Adriana I. Altamirano Ruiz. “Estudiantes Migrantes De Retorno En México. Estrategias emprendidas para acceder a una educación universitaria.” Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa. June 25, 2015. http://www.redalyc.org/html/140/14042022008/.

[xxviii] Ibid.

[xxix] Anderson, Jill. “Bilingual, Bicultural, Not Yet Binational: Undocumented Immigrant Youth in Mexico and the United States.” October 2016. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/bilingual_bicultural_not_yet_binational_undocumented_immigrant_youth_in_mexico_and_the_united_states.pdf

[xxx] Ibid.

[xxxi] de Vries, Wietse and Francisco Romero. Chapter 4. Mexico: Higher Education, the Liberal Arts and Prospects for Curricular Change. Routledge, 2012. pp.75-99. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313118558_Chapter_4_Mexico_Higher_Education_the_Liberal_Arts_and_Prospects_for_Curricular_Change

[xxxii] Vallone, Deanie. “So What is Liberal Arts, and Why Does Everyone in America Study It?” The Independent. November 11, 2013. http://www.independent.co.uk/student/study-abroad/so-what-is-liberal-arts-and-why-does-everyone-in-america-study-it-8933110.html

[xxxiii] Ibid.

[xxxiv] Magaziner, Jessica, and Carlos Monroy. “Education in Mexico.” WENR. August 16, 2016. http://wenr.wes.org/2016/08/education-in-mexico.