Links between Gold and Coca in Colombia

By Joseph Green, Extramural Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF version of this article, click here.

Following the recognition that Colombia is once again the world’s top coca producer, with a 39 percent production increase in 2015 alone, experts have been analyzing the data to determine what could have caused a spike so soon after its historic low in 2013.[1] [2] Studies by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) have linked flagging levels of coca production to that of the more recent phenomenon of illegal gold mining, and organizations like the UNODC and the Ideas for Peace Foundation (FIP) in Bogotá recognize illegal mining as an additional factor related to the drug trade that needs to be observed in order to better comprehend and combat illegal practices regarding both materials.

Gold and coca are intricately tangled in webs of financial corruption and violence in Colombia. While the implications of coca cultivation have been well-publicized since the heyday of the cocaine cartels in the 1980s, illegal gold mining by similar armed groups today is less understood. For instance, the guerrillas of the leftist Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN) are often cited as being the principal offenders. Both groups have expanded into drugs and illegal mining to complement “traditional” fundraising efforts like kidnapping and extortion. None of these activities are exclusive to the guerillas; instead, the common denominator is profitability.

Illegal Mining

Illegal mining operations are those that do not adhere to zoning, licensing, environmental, and a variety of other commercial regulations designed for the sector. In this way, participants in the industry are afforded opportunities to bring in new streams of revenue, often with capital gained through other unlawful financial activities. Industry leaders include guerrilla groups, paramilitary groups, and organized crime elements, while the labor force supporting their activities consists of poor rural dwellers, indigenous people, and garimpeiros (migrants with job experience from similar operations in Brazil).[3] Setting up operations in remote areas, the workers clear the land and excavate open-air mines with bulldozers. The loose material is filtered first with water, and then with mercury or cyanide; once the precious metals are extracted, and toxic byproducts are abandoned.[4] Spurred by the high gold prices of recent years, illegal mines provided up to 87 percent of Colombia’s annual gold exports.[5] Illegal gold mining charges are difficult to establish if the perpetrators are not caught in the act, and carry lesser sentences in any case. Currently, the only formal incentive for change is the option to apply for the legalization of ongoing, illegal mining operations.[6]

Coca Production

The coca plant is native to the Andean region of South America and has been used for medical and ceremonial purposes by indigenous peoples since ancient times. After the dismantling of the major drug cartels in Colombia, the guerrillas, paramilitaries, and criminal gangs moved in to take their place. To take down such illegal cultivation, the Colombian government has traditionally used the chemical glyphosate–known colloquially as “Roundup”–on coca fields. This was largely done by aerial “crop-dusting” from the Clinton-era Plan Colombia until 2015, when the tactic was suspended due to effects on environmental and human health. Manual spraying (previously a compliment to aerial spraying) is now the only method of Roundup distribution and has the added benefit that the plants are also physically removed. In this way the new method lengthens the interval before production resumes and in theory, more effectively detains production.[7] On the other hand, manual spraying is slower, more labor-intensive, and reaches fewer coca fields–contributing to the increase in production.

As another method of discouraging coca cultivation, the government has introduced crop substitution programs, which use subsidies, education, and technical assistance to incentivize former coca growers to return to traditional crops. These programs have had success by addressing the economic realities that forced many into coca cultivation in the first place, but their implementation has been limited so far.

Shared Ties

Coca and illegal mining operations are linked in two ways. They are managed by the same extralegal armed groups, and their respective land needs have relegated them to the same isolated production centers. Thirty-eight percent of the overall territory affected by illegal mining is also affected by coca cultivation. Furthermore, the top-producing departamentos (Colombian states) tend to have high levels of both coca and gold–particularly Cauca, Nariño, Putumayo, and Caquetá.[8] [9]

Drug eradication efforts are commonly seen as having a direct cause-and-effect relationship with the supply; by this logic, chemical spray and crop incentives would be the major causes of the pre-2014 decline in coca output. However, FIP’s analysis states that this is not the case, but instead claims that the traditional actors in the coca sector simply branched out into extractive mining in pursuit of higher profits brought about by the steep rise in gold prices between 2007 and 2012.[10] According to FIP, now that the price relationship between gold and cocaine has changed, these actors are starting to return to the coca fields.

Price Relationship

The fact that gold and coca are often produced and sold by the same parties means that they compete for the same resources. In turn, the two products have an inverse relationship in which a difference in the profitability of one product affects its priority over the other. The phenomenon is encompassed in a concept called “relative profitability.” Economists Susan Grant and Chris Vidler discussed relative profitability and its importance for organizations that can easily produce different products or services: “If supplying an alternative product [gold] becomes more profitable the supply of the good in question [coca] will fall…On the other hand if the supply of an alternative [gold] becomes less profitable there could be a shift…showing an increase in supply [of coca].”[11]

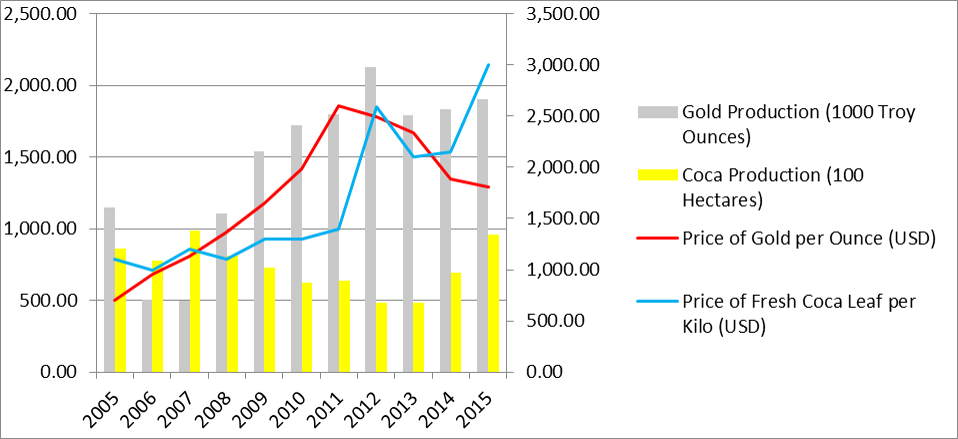

The inverse relationship can be seen in the graph above.[12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] As the price of gold rose compared to a fairly stagnant coca price, production of the former went up while coca production went down. Once the price of gold started to fall, gold production fell as well and coca production began to mount again.

There are other factors beyond price that affect profitability. Illegally mined gold is processed onsite, while coca processing is decentralized and the labs and fields tend to be far removed from each other, making for a more complex logistics system. On the other hand, coca cultivation requires less equipment and initial investment than mining, and each hectare planted produces an average of 4,800 kilos of coca leaf per year.[20] At any rate, gold has proven 20 times more profitable than coca at its peak price.[21] The basic tenets of supply and demand compounded the effects of the subsequent drop in gold prices; as the available supply of coca went down, the price went up, thus increasing its profitability relative to gold even more. Meanwhile, though gold prices are currently dropping, they are still well above where they were a decade ago, so the abandonment of illegal mining will likely be more gradual than that of coca. By 2015, illegal mining’s contribution to Colombia’s overall gold production already had dropped five percentage points compared to the year before.[22]

Implications for Policy

Though it is nowhere near the record high for coca production, the present increase in coca acreage still presents a complicated situation for Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos. A growing fiscal deficit makes it increasingly difficult to assign the necessary resources to combat the coca cultivations. Not even priority anti-drug programs in one of the best-performing economies in Latin America are immune to the region’s current economic difficulties. On the other hand, successful efforts have pushed illegal activities into increasingly consolidated areas, such as Colombia’s Pacific region, making them easier to control. The imminent peace agreement with the FARC will ostensibly remove one of the major players in both illegal mining and all facets of coca commercialization from the equation, and officials hope that the legalization of medical marijuana will further restrict illicit revenue streams.[23] The fact remains that the larger problem is fundamentally external, with the majority of the coca being processed and exported to satisfy demand in Europe and North America.[24]

In the short term, Colombia can combine its actions against coca and illegal mining to address the common source; this would not only be more effective, but also more efficient, especially in light of continually shrinking budgets. Illegal mining has only recently begun to be studied at a deeper level, and this must be encouraged to continue in order to develop an appropriate response to the situation.[25] In addition, more action can then be taken against illegal mining along with stricter regulations on gold sales.

As FIP points out, all presidents have bad years in the battle against coca, including the notoriously heavy-handed ex-president Álvaro Uribe.[26] A more comprehensive treatment of the issue now will elude the kind of violence that Uribe resorted to in his time and help propel Colombia into a new era of peace and prosperity.

By Joseph Green, Extramural Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Original research on Latin America by COHA. Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and instituional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to LatinNews. com and Rights Action.

Featured Photo: Police destroying a coca lab. Taken from Flickr.

[1] El Espectador, ¿Por qué Colombia volvió a ser el mayor productor de coca en el mundo?, July 8, 2016. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.elespectador.com/noticias/judicial/colombia-volvio-ser-el-mayor-productor-de-coca-elmundo-articulo-642227

[2] Daniel Rico Valencia, 96.000 hectáreas de coca, y sumando, Fundación Ideas para la Paz, July 12, 2016. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.ideaspaz.org/publications/posts/1359

[3] Jhon Torres Martínez, Minería ilegal en Colombia: Nuevos desiertos avanzan detrás de la fiebre del oro, El Tiempo, December 17, 2015. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.eltiempo.com/multimedia/especiales/mineria-ilegal-en-colombia-nuevos-desiertos-avanzan-detras-de-la-fiebre-del-oro/16460299

[4] Ibid

[5] Ibid

[6] Frédéric Massé and Juan Munevar, Due Diligence in Colombia’s Gold Supply Chain, OEDC, 2016. Accessed August 14, 2016. https://mneguidelines.oecd.org/Colombia-gold-supply-chain-overview.pdf

[7] UNODC, Colombia: Monitoreo de territorios afectados por cultivos ilícitos 2015, July 2016. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/Colombia/Monitoreo_Cultivos_ilicitos_2015.pdf

[8] UNODC, New Colombia report sheds light on link between gold extraction and criminal activities, August 9, 2016. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2016/August/new-colombia-report-sheds-light-on-link-between-gold-extraction-and-criminal-activities.html?ref=fs1

[9] UNODC, Colombia: Explotación de oro de aluvión, Evidencias a partir de percepción remota, June 2016. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.unodc.org/documents/colombia/2016/junio/Explotacion_de_Oro_de_Aluvion.pdf

[10] Daniel Rico Valencia, 96.000 hectáreas de coca, y sumando, Fundación Ideas para la Paz, July 12, 2016. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.ideaspaz.org/publications/posts/1359

[11] Susan Grant and Chris Vidler, Economics in Context (London: Heinemann, 2000), 42

[12] UNODC, Colombia Coca Cultivation Survey 2006, June 2007. Accessed August 15, 2016. http://www.unodc.org/pdf/research/icmp/colombia_2006_en_web.pdf

[13] UNODC, Colombia: Monitoreo de territorios afectados por cultivos ilícitos 2010, July 2011. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/Colombia/Colombia-cocasurvey2010_es.pdf

[14] UNODC, Colombia Coca Cultivation Survey 2012, June 2013. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/Colombia/Colombia_Coca_Cultivation_Survey_2012_web.pdf

[15] UNODC, Colombia Coca Cultivation Survey 2013, June 2014. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/Colombia/Colombia_coca_cultivation_survey_2013.pdf

[16] UNODC, Colombia Coca Cultivation Survey 2014, July 2015. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/Colombia/censo_INGLES_2014_WEB.pdf

[17] UNODC, Colombia: Monitoreo de territorios afectados por cultivos ilícitos 2015, July 2016. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/Colombia/Monitoreo_Cultivos_ilicitos_2015.pdf

[18] Gold Price, Gold Price. Accessed August 15, 2016. http://goldprice.org/

[19] SIMCO, Historico de Producción de Oro. Accessed August 15, 2016. http://www.upme.gov.co/generadorconsultas/Consulta_Series.aspx?idModulo=4&tipoSerie=116&grupo=355

[20] UNODC, Colombia: Monitoreo de territorios afectados por cultivos ilícitos 2015, July 2016. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/Colombia/Monitoreo_Cultivos_ilicitos_2015.pdf

[21] Jhon Torres Martínez, Minería ilegal en Colombia: Nuevos desiertos avanzan detrás de la fiebre del oro, El Tiempo, December 17, 2015. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.eltiempo.com/multimedia/especiales/mineria-ilegal-en-colombia-nuevos-desiertos-avanzan-detras-de-la-fiebre-del-oro/16460299

[22] Pedro Vargas, Así ‘lavan’ el oro de la minería ilegal en el país, Portafolio, June 10, 2016. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.portafolio.co/economia/gobierno/lavan-oro-mineria-ilegal-pais-497191

[23] Ezra Kaplan, Colombia’s New, Legal Drug Barons Focus on Medical Marijuana, The New York Times, August 4, 2016. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/05/business/international/colombia-medical-marijuana-drugs.html?_r=0

[24] UNODC, The Global Cocaine Market, World Drug Report 2010. Accessed August 14, 2016. https://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr/WDR_2010/1.3_The_globa_cocaine_market.pdf

[25] UNODC, Colombia: Explotación de oro de aluvión, Evidencias a partir de percepción remota, June 2016. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.unodc.org/documents/colombia/2016/junio/Explotacion_de_Oro_de_Aluvion.pdf

[26] Daniel Rico Valencia, 96.000 hectáreas de coca, y sumando, Fundación Ideas para la Paz, July 12, 2016. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.ideaspaz.org/publications/posts/1359