Lessons Not Learned From the Past: United States-Colombia Free Trade Agreement at Stake

With the enactment of the U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement (FTA) on May 15, 2012, Washington continues to implement free trade agreements as its basic strategy of fostering trade and development in Latin America. While it may be proved that free trade agreements can benefit particular countries’ industries and stockholders, this does not mean that they have evolved into being a perfect partnership for both countries. To the contrary, it has often been charged that one country might benefit more than the other. Previous U.S. FTAs, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), have raised concerns about U.S. intentions and results. Once again, a number of Latin American leaders, induced by a thirst for growth, seem to have forgotten a number of lessons from the past and have not attempted to implement alternatives to counteract the negative consequences associated with FTAs.

Economic growth promotion

With a burgeoning middle class and a growth rate of around 6 percent per year, Colombia has developed into the third largest economy in South America. Prior to the ratification of the U.S. FTA, commercial trends between Colombia and the United States, its main trading partner, were continuously evolving in the early 2000’s, leading to aspirations throughout the hemisphere for a comprehensive trade agreement.[1] The old Andean Trade Preference Agreement had maintained barriers on 20 percent of U.S. goods, which has discouraged long-term investment in Colombia. After many years of discussions, the FTA between Colombia and the United States came into force this year, offering duty free access for goods and services, and promoting outside investments in the region.

It can be argued that the agreement has mainly facilitated U.S. exports of grain and dairy products to Colombia, while Bogota’s trade is focused more on the sale abroad of horticultural products and tropical fruits such as bananas and coffee.[2] Their comparative advantages in trade matters were perfectly illustrated by the initial shipments between the two countries; Colombian flowers and U.S. Harley-Davidson motorcycles.

According to the International Trade Commission, the United States exported goods worth a total of $12 billion USD to Colombia in 2011, of which $1.3 billion USD were in agricultural exports. Furthermore, Colombian exports to the United States grew from $2 billion USD in 2010 to $2.5 billion USD in 2011.[3] Although these figures revealed significant economic growth, as indicated by both governments, the agreement in fact was more often asymmetrically at the expense of Colombian agricultural and extractive interests.

Countries’ asymmetries

The United States and Colombia maintain that the agreement will be implemented over a period of fifteen years, giving Colombia enough time to prepare its economy for the explosive trading power of the United States. Nevertheless, the agreement will immediately eliminate duties for about 70 percent of U.S. farm exports. In fact, Colombia’s Minister of Agriculture, Juan Camilo Restrepo, has acknowledged that Colombia is “not ready” and needs to adapt quickly, requiring crucial investments to modernize its economy and overcome its infrastructural weaknesses.[4] The government still has to implement alternative programs and initiatives that retain important differences when it comes to competitive factors.

Following the agreement, Colombia has had to remove its variable tariff and price band protections, which previously had been used to stabilize prices and counter food insecurity. As the French agricultural think tank Momagri points out, the FTA only implements temporary safeguards for goods not already subject to duty-free provisions, while ignoring the World Trade Organization (WTO) guidelines regarding safeguard mechanisms. However, the FTA’s safeguards “can only be triggered by sudden increases in the quantity of goods, not volatility in prices.” Hence, the agreement leaves food prices at the mercy of the frequent price changes of international markets. [5]

Colombia’s agriculture sector will have to face competition from the United States’ large and efficient industry. As a result, the Colombian administration has decided to implement diverse subsidies to help farmers, assigning 1.15 percent of the 2012 budget to agriculture.[6] Noting the lack of proper financial aid and investment aimed at farmers, the imbalances between the two countries are likely to continue to remain formidable.

Social Costs

The U.S.-Colombia FTA, a supposedly benevolent 21st century trade policy aimed at benefiting more than 3 million of Colombia’s small agricultural producers, is supposed to affect 89 percent of all of its farmers. The uncontrolled flood of U.S-subsidized agricultural products into Colombia’s domestic markets could also undermine rural livelihoods and food security due to the increasing dependence on imports. Moreover, the British-based Oxfam charity reported in 2009 that the income of Colombian farmers had dropped as much as 48.5 percent of the sector. As 68 percent of them already earn less than the minimum salary, the FTA is identified by many as an increasing threat to their well-being.

This new dependency leaves consumers at the mercy of the international marketplace, ignoring the damaging consequences of the 2008 global financial crisis. Despite the baleful experiences of CAFTA and NAFTA, when competition from the north resulted in displacing thousands of Latin American farmers, the governments ignored the harmful effects of U.S. subsidized products. Similar free-trade agreements such as CAFTA and NAFTA dismantled less-developed countries’ local agricultural sectors. This resulted in the loss of 1.3 million jobs in the Mexican agricultural sector, while the United States maintained and protected its own agricultural industry.[7]

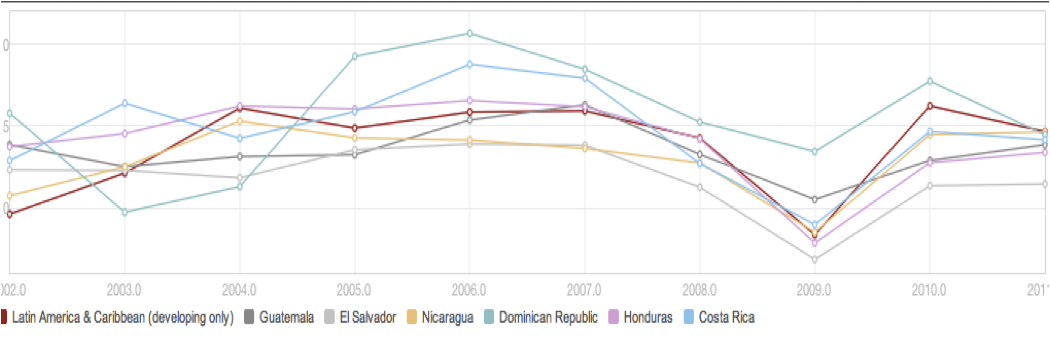

Although CAFTA members expected substantial economic growth after the agreement was announced, they actually experienced GDP decreases. With its economy growing at 5.9 percent in 2011 and with a similar forecast for 2012, Colombia will have to prove that other countries’ dismal economic results and disappointing statistics can be explained more by the economic crisis than by their free-trade agreements. [8]

Colombia has an abysmal record of trade unionist killings (51 were assassinated in 2010), but labor rights are expected to only worsen under the FTA. In fact, the FTA labor chapter contains language on working rights and other conditions that is weaker than the policies previously governing U.S.-Colombia trade.[9]

Ignored risks and alternatives

A number of experts will agree that increased rural poverty will be triggered by the agreement. This could also negatively affect conflict zones in which a return to coca cultivation or other factors would prompt migrations as a way to escape poverty. The agreement will undermine the economic viability of other food crops for Colombian peasants, such as cacao, and will prevent agricultural alternatives. The Colombian government has committed many errors by ignoring the country’s brutal past, with 5.2 million Colombians forced to migrate over the last 12 years due to the ongoing internal conflict between the government’s forces linked in open alliance with violent paramilitaries.[10]

Although it can be argued that the above is a short-term risk and that the agricultural sector will eventually improve, the potential consequences cannot be ignored. The government of Colombia should implement the necessary measures to increase the competitiveness of the country’s agricultural sector while protecting at least some of its more sensitive products that are often used by small farmers as alternative crops to coca production. Afro-Colombian communities, mainly occupying conflict zones, were not even remotely informed about the agreement, and there has been no successful incentive introduced to push towards an agro ecology approach, which is more respectful of natural assets and culture.[11] Despite these disadvantages, this painfully inadequate policy has been chosen by the Colombian government as the most suitable method of development.

Recent Events

Following the inauguration of the bilateral FTA, President Santos announced major social reforms and basic peace talks with FARC rebels. Despite legislation passed to compensate victims of civil conflict, enactment of social reforms and the long awaited peace negotiation, casualties among Colombia’s indigenous population have continued, such as on August 15 when activist Lisandro Tenorio was killed.[12] Furthermore, countless acts of intimidation and murder of human rights activists, land rights defenders, and trade unionists still continue.[13]

Economically, Colombia shows mixed results since the agreement’s inauguration. Colombian exports to the United States grew by 10.4 percent; however, 90 percent of those exports had previously entered the United States duty free. In addition, Colombian imports have increased by $391 million USD, creating a dependency on foreign goods.[14]

Conclusion

Like several other Latin American countries, Colombia has chosen to follow a neoliberal approach in order to increase its growth and foster development. Without denying the positive consequences of the free-trade agreements, these policies do little to protect workers’ rights and rural livelihoods. Both governments have not offered any viable alternatives to the less-developed countries, leaving them to compete in more competitive markets.

Even with alternatives and associated issues like agro ecology and food sovereignty, the Colombian government does not seem to be particularly eager to support what could be more sustainable approaches than it is now taking. It is inevitable that the continuation of U.S. free trade agreements towards receptive Latin American governments will only reiterate previous negative results. Once again, history is being repeated but useful lessons have not necessarily been learned, as authentic growth is inappropriately linked with what often turns out to be a skewed opportunity for development.

Mar Guinot Aguado, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Updated by J.T. Larrimore, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated.

Sources:

[1] Diana Villiers Negroponte, “Celebrating Colombia’s Free Trade Agreement,” Brookings Institution, http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/up-front/posts/2012/05/17-colombia-free-trade-negroponte.

[2] U.S. Department of Agriculture, “U.S. & Colombia Trade Promotion Agreement Benefits for Agriculture,” Washington, D.C: May 2012, http://www.fas.usda.gov/info/factsheets/Colombia/Colombia%20TPA%20Detailed%20Fact%20Sheet%2005-15-12.pdf.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Mimi Whitefiled and Jim Wyss, “U.S. – Colombia Free Trade Agreement goes into effect,” The Miami Herald, August 20, 2012, http://www.miamiherald.com/2012/05/14/2799483/us-colombia-free-trade-agreement.html

[5]Karen Hansen-Kuhn, “The U.S.-Colombia trade agreement: A volatile agenda on agriculture,” Movement pour une organization mondiale de l’agriculture, http://www.momagri.org/UK/focus-on-issues/The-U-S-Colombia-trade-agreement—A-volatile-agenda-on-agriculture-_916.html.

[6] Hernan Perez Zapata, “TLC vs Soberania Alimentaria,” Homenje al campesinado por Guilloume, 2nd Edition, http://alainet.org/images/2A_%20EDICION%20TLC%20VS%20SOBERANIA%20ALIMENTARIA%20ENERO%2012,%202012_%20CORREGIDA.pdf.

[7] John J., Audely, Demetrios G Papademetriou, Sandra Polaski, and Vaughan Scott, “NAFTA’s Promise and Reality, Lessons From Mexico For the Hemispheric,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2004, http://www.globalexchange.org/sites/default/files/carnegie_nafta1.pdf.

[8] The World Bank, GDP growth annual, Washington, D.C.: 2012, http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG/countries/CO?display=graph.

Matthew Bristow, “Colombia Central Bank Forecasts 2013 GDP Growth of 2% – 5%,” Bloomberg, July 31, 2012, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-07-31/colombia-central-bank-forecasts-2013-gdp-growth-of-2-5-.html

[9] Hernan Perez Zapata, “TLC vs Soberania Alimentaria,” Homenje al campesinado por Guilloume, 2nd Edition, http://alainet.org/images/2A_%20EDICION%20TLC%20VS%20SOBERANIA%20ALIMENTARIA%20ENERO%2012,%202012_%20CORREGIDA.pdf.

[10] Lisa Haugaard, Kelly Nicholls, and Gimena Sanchez-Garzoli, “U.S.-Colombia FTA Action Plan Falls Short of Protecting Rights,” Washington Office on Latin America, http://www.wola.org/news/us_colombia_fta_action_plan_falls_short_of_protecting_rights.

[11] Latin America Working Group, “Talking Points on Negative Impacts on the U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement,” http://www.lawg.org/storage/documents/Colombia/Colombia_FTA_Talking_Points_2011.pdf.

[12] Amnesty International, “Colombia: Indigenous leader killed amid ongoing fighting in Cauca,” August 15, 2012, http://www.amnesty.org/en/for-media/press-releases/colombia-indigenous-leader-killed-amid-ongoing-fighting-cauca-2012-08-15.

[13] Amnesty International, “Document – Colombia: Trade Unionists’ Live in Danger in Colombia,” August 9, 2012, http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/AMR23/029/2012/en/d6e5adf3-d292-440e-a532-b211140af6d4/amr230292012en.html.

[14] Trading Economics, “Colombia Imports,” accessed October 1, 2012, http://www.tradingeconomics.com/colombia/imports.

See Also:

Green Roofing in Mexico City: A Sustainable Success in Countering Food Insecurity and Climate Change