Holding Salvadoran War Criminals Accountable: The Massacre at University of Central America, San Salvador, 1989

This essay will examine some new developments in the case of one of the most notorious war crimes committed by the Salvadoran security forces during the twelve year long civil war: the massacre on the campus of the José Simeón Cañas University of Central America (UCA) in San Salvador on November 16, 1989. This is an immensely important issue because it could begin to balance the dialectic between impunity and accountability to the side of accountability. For the first time, a high-ranking army officer may soon be tried for this crime. A number of legal actions have converged to make this possible, with the main players being a Spanish Court, US immigration authorities, and the methodical work of the Center for Justice and Accountability (CJA). Their work, in turn, would not have been possible if not for the dedication of the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights and the late Congressman Joseph Moakley early on in the investigation.1 We begin with a brief description of the crime and its historical context, and then turn to the significance of the conviction last month of Inocente Orlando Montano on charges of immigration fraud and perjury.

The Crime and the Context

According to the findings of the UN-sponsored Commission on the Truth for El Salvador,2 on November 15, 1989, Chief of Staff of the Salvadoran Armed Forces Rene Emilio Ponce, with the collusion of Colonel Inocente Orlando Montano and other high ranking officers, gave orders to Colonel Guillermo Alfredo Benavides to kill the long time rector of the UCA, Father Ignacio Ellacuría and to leave no witnesses. The following day, a unit of the US trained Atalactl battalion entered the UCA and ordered Father Ellacuría and four other faculty members, also Jesuit priests, to lay face down in the courtyard. A sixth priest was found inside the residence and the housekeeper and her fifteen-year old daughter were discovered in a nearby room. The Truth Commission describes what happened next:

The lieutenant in command, José Ricardo Espinoza Guerra, gave the order to kill the priests. Fathers Ellacuría, Martín-Baró and Montes were shot and killed by Private Oscar Mariano Amaya Grimaldi, Fathers López and Moreno by Deputy Sergeant Antonio Ramiro Avalos Vargas. Shortly afterwards, the soldiers, including Corporal Angel Pérez Vásquez, found Father Joaquín López y López inside the residence and killed him. Deputy Sergeant Tomás Zarpate Castill shot Julia Elva Ramos, who was working in the residence, and her 16-year-old daughter, Celina Mariceth Ramos. Private José Alberto Sierra Ascencio shot them again, finishing them off.3

These cold-blooded murders were carried out by government forces in the course of an FMLN guerilla offensive that took the civil war to streets of San Salvador. As veteran commentator Peter Kornbluh points out, “Embarrassed by the strength of the insurgency, senior Salvadoran military officers decided to kill as many activists, labor leaders, and “subversive elements” as they could find…”.4 Why launch an assault on the UCA? The university was obviously not a military threat, having been surrounded by a security perimeter of about 300 soldiers days before the murders. Rather, it was the mission and praxis of the university that made it “subversive” to oligarchic interests and ideology.

Since its founding in 1965, the UCA has played a prominent intellectual role in the cultural, social, and political life of the country. The University’s mission has been informed by a liberation theology motivated by a preferential option for the poor.

Father Ignacio Ellacuría, Rector of the UCA from 1979 until his death in 1989, was a renowned theologian and public intellectual; he wrote numerous articles on liberation theology and on the role of the university in the life of the country. In “The University, Human Rights and The Poor Majority,” he states:

The university will have to set as its ultimate overall objective the attainment by the poor majority both of living standards sufficient for meeting their basic needs in a decent manner and of the highest degree of participation in the decisions that affect their own fate and that of society as a whole.5

As Hugh Lacey points out, practicing this option for the poor is not only a moral imperative, but opens a path to a deeper, more accurate understanding of social reality:

A fundamental theme of liberation theology is that contact with the sufferings of the poor, and with the communal struggle to overcome those sufferings, provide the key to understanding social reality—a contact that is immediate, involved, expressive of compassion and solidarity, and critically articulated.6

Ellacuría was well aware that the UCA’s mission required praxis in the form of a university response to the human rights violations going on in the country at the time and that this, in itself, posed a risk of persecution. In 1982, as the counter-insurgency intensified, Ellacuría wrote:

[The university’s] response must reflect a genuine love for the poor majorities, a passion for social justice, and a courage to meet the attacks, the misunderstandings, and the persecution that will ensue because of its stand on behalf of the poor.7

The UCA did indeed experience persecution, including death threats and bombings starting in the early 1970’s. Martha Doggert has provided a chronology of the bombings of UCA facilities, assassinations of priests and laypersons, death threats directed at the Jesuit faculty, campaigns to defame the UCA in the national media, and government attempts to strip the Jesuits of their Salvadoran citizenship.8

The relationship of the Jesuit faculty to the army and the government was not, however, always adversarial. In October 1979, at a crucial juncture in modern Salvadoran history, there is evidence that Ellacuría offered assistance in drafting a set of reforms that were announced in the form of a proclamation by a Revolutionary Governing Junta (Junta Revolucionaria de Gobierno, JRG) that had just come to power through a coup.9 The JRG was constituted and supported by a broad based coalition, including the reformist Young Military (Juventud Militar), led by Colonel Adolfo A. Majano. If the reformists had been able to implement a promised set of political, social, and economic reforms, civil war might have been averted.10 The Carter Administration, which was supplying military and logistical assistance to the Salvadoran government, also thought the JRG could succeed, but failed to apply sufficient leverage in support of moderates on the Junta. After the oligarchic forces and their hard line allies in the military defeated reformist efforts and isolated Colonel Majano, the JRG fell apart. Although a series of new Juntas were formed, it was too late; the country spiraled into civil war. The following year, the war against the church was intensified with the well-planned assassination, on March 24, 1980, of Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero.

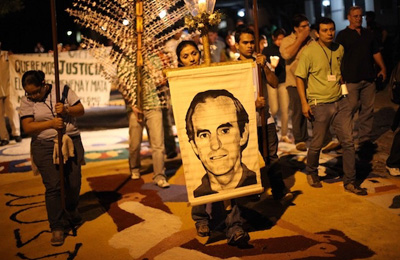

Despite the intensifying persecution of the popular church and threats against the UCA, the university maintained its academic autonomy and faithfulness to its mission. Its Rector, Father Ignacio Ellacuría, to the chagrin of the Salvadoran security forces, continued to advocate for a negotiated settlement to civil war, expose the underlying causes of the conflict, and promote social and economic justice. It was this profound and committed spirituality the high command of the Salvadoran Armed Forces tried to destroy on November 16, 1989.

The Aftermath: Shock, International Outrage, Cover Up, and Impunity

The scene in the immediate aftermath of the killings revealed the shallowness and cynicism of the perpetrators. Spray painted messages on campus walls and a staged gun battle were used to try to make it look like the FMLN had carried out the attack, unlikely not only because of a lack of motive, but because the assassins had to pass through a tight security perimeter. Carmen Maria was a secretary in the UCA for twenty four years and remembers being there just after the murders. Speaking to the immediate impact of the crime, she recalls everyone being surprised because they could not comprehend that “the military had it in them to commit such a crime, and no one knew exactly how far-reaching [the State-sponsored] attacks would be.” She remembers the bodies as extremely cold and grotesque, and in the immediate aftermath, no one left the university. It was a trauma that had the immediate effect of uniting the university community. She describes the overarching feeling that it was important to continue working and living amidst the chaos, because they “did not want to cry, but to use their pain to do something.”

In addition to the trauma inside El Salvador, these killings sent shock waves throughout the Americas and Europe and drew attention to the failed policy of the US towards El Salvador. It was time to change course, push for a negotiated solution to the war, and to hold war criminals directly responsible for their deeds. As the Center for Justice and Accountability points out:

The Jesuits Massacre persuaded the U.S. Congress to create a special investigative task force in 1989, led by Congressman Joseph Moakley. The findings of Moakley’s Task Force’s revealed that the upper echelon of the Salvadoran officer corps had been responsible for the murders of the Jesuits, and that 19 of the 26 Salvadoran officers responsible for the murders had received military training at the U.S. Army School of the Americas (SOA). The report set in motion an international process to end the conflict.11

Under international pressure, including a congressional committee investigation led by Congressman Joseph Moakley and the legal representation of the Jesuits by the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights,12 the Salvadoran authorities launched an investigation into the massacre at the UCA. Justice for the victims, however, has not been expeditious. Salvadoran investigators did make a number of arrests, which subsequently led to several prosecutions and convictions. However, these legal proceedings were internally fraught with irregularities. There was a cover up, destruction of evidence, and intimidation of witnesses by the Salvadoran authorities.13 High-ranking officers were protected from prosecution while several lower ranking soldiers were sentenced to jail time for murder and conspiracy to commit acts of terrorism. In a speech at the UCA on July 1, 1991, Moakley directed part of his comments directly to the Defense Minister Ponce:

You have an institutional problem when it is the institution that instills fear in potential witnesses; when it is the institution that teaches its officers to be silent, to be forgetful, to be evasive, to lie; when it is the institution that demands loyalty to the armed forces above loyalty to the truth or to honor or to country.14

When the peace accord that brought the war to an end was signed in 1992, there was hope that this institutional corruption of the Salvadoran security forces could be addressed so that war criminals would be held accountable for their crimes. But in 1993 an amnesty law was passed under which the soldiers jailed for the UCA massacre were freed and those who committed war crimes were protected from prosecution. Those who violated human rights during the war, however, were not to be protected from the investigative arm of the Truth Commission on El Salvador.

The Truth Commission

The UN-sponsored Truth Commission on El Salvador investigated human rights abuses that occurred during the civil war. Since the first truth commission was implemented in Uganda in 1974, they have played an important role in the investigation of human rights violations, but a limited role in holding perpetrators accountable for their crimes. In the case of El Salvador, unlike the role of the commission in South Africa, there were neither confessions by the war criminals nor displays of forgiveness by the survivors.

The Truth Commission on El Salvador operated for eight months from July 1992 to March 1993 and its mandate was to investigate serious acts of violence committed during that country’s civil war (1979 – 1991) and to recommend methods of achieving national reconciliation.15 Among more than 22,000 documented complaints, the truth commission determined that the vast majority of cases were committed by the Salvadoran security forces.16 The commission’s final recommendations included the dismissal of culpable army officers and civil servants from government employment, but it did not call for prosecution of incriminated perpetrators because it saw the Salvadorian legal system as incapable of executing such prosecutions effectively. The commission recommended payment of reparations to the victims but it was not until January 2012 that some action was taken on this issue. At the commemoration of the Peace Accords, President Mauricio Funes asked for forgiveness on behalf of the state for the massacre at El Mozote (in December 1981) that had been perpetrated by the army and announced the establishment of a national program for reparations for the victims of this and other violations of human rights that occurred during the armed conflict.17

In its review of the Truth Commission on El Salvador, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) stressed that,

…Despite its ‘highly relevant’ role, [truth commissions] ‘cannot be considered as a suitable substitute for proper judicial procedures as a method for arriving at the truth. The value of truth commissions is that they are created, not with the presumption that there will be no trials, but to constitute a step towards knowing the truth and, ultimately, making justice prevail. Nor can the institution of a truth commission be accepted as a substitute for the state’s obligations, which cannot be delegated, to investigate violations committed within its jurisdiction, and to identify those responsible, punish them, and ensure adequate compensation for the victim…18

The IACHR’s recommendations likely went unheeded because the right wing ARENA party that dominated the government during the war remained in power another two decades. As legal expert Margaret Popkin points out, a peace process “is challenging in a context such as El Salvador’s where the regime responsible for many human rights violations remained in power, where state institutions remained weak, and where those primarily responsible for the violations retained significant power.”19 As mentioned above, this “significant power” of ARENA and its allies would be quickly translated into the legalization of impunity.

The 1993 Amnesty Law: The Legalization of Impunity

The Amnesty Law was passed by the National Assembly on March 20, 1993 by ARENA and other right wing parties in a 47 to 8 vote (with 13 abstentions) and signed into law by President Cristiani just five days after the Truth Commission on El Salvador issued its report. In effect, the passage of this law was a self-amnesty, not a popular act of forgiveness, because it was passed by the same governing party under which the abuses took place. It met with the immediate opposition of the UCA, some Salvadoran human rights organizations, and the international human rights community. In a country where more than 75,000 non-combatants were killed, largely by the security forces and their allied death squads, the amnesty law continues to deprive survivors of closure and the dead of justice and retribution.

By the late 90’s, international pressure with regard to resolving the Jesuit case began to intensify. In 1999, the Inter-American Commission ruled that El Salvador’s amnesty law violated international law by foreclosing further investigation of the 1989 murder of six Jesuit priests and two women.20 This law is still hotly controversial; Amnesty International strongly encouraged the repeal of the 1993 amnesty law in March 2010. Last year, the mere rumor that the Supreme Court of El Salvador was about to rule on the constitutionality of the Amnesty Law provoked ARENA to attempt legislative strategies to weaken the courts prerogatives, causing a constitutional crisis. The examples of Uruguay and Argentina, which have repealed their amnesty laws, have shown that it is possible to overcome great political obstacles to end the reign of impunity.

While amnesty for war criminals continues to prevail in El Salvador, a tangible legal initiative for justice came from outside the country in the case of the infamous Jesuit murders. In 2008, nearly two decades after the massacre at the UCA, a complaint in the Spanish High Court brought hope that the perpetrators of this crime could some day be brought to justice. While the cause of universal jurisdiction motivated the Spanish court to take this case, it was litigated under a 2009 Spanish law that provides for jurisdiction when the victims are Spaniards.21 On May 30, 2011 a Spanish court brought formal charges against 20 Salvadoran military officers and soldiers for their participation in the 1989 massacre.22 This effort at attaining accountability was blocked by the Supreme Court in El Salvador in May 2012 when the court denied Spain’s request for the extradition of thirteen of the military officers responsible for the massacre at the UCA.23 The Salvadoran court ruled that Salvadoran law prohibited the extradition of citizens for crimes committed prior to 2000. This ruling, however, does not protect those charged who are residing outside of El Salvador.

The Conviction of Inocente Orlando Montano: The Erosion of Impunity

Fourteen years after the massacre at UCA, there is a break in the case. On September 11, 2012, Inocente Orlando Montano was convicted in a US federal court on charges of immigration fraud and perjury. Montano had lied on applications for temporary protective status (TPS), concealing his former occupation as a military commander in the Salvadoran army. Assistant US Attorney John Capin said Montano was “motivated by a desire to conceal human rights violations that he participated in, or sought to conceal what he was involved in in El Salvador.”24 Withholding this information was no small omission. Montano was among the high-ranking military officers indicted by a Spanish court in 2011 for collusion in the UCA massacre of November 16, 1989. Now, that court is seeking Montano’s extradition from the US to stand trial in Spain. He is currently under house arrest pending his sentencing hearing scheduled for December 18, 2012. While it is not clear whether the US will comply with this request, a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) press release does not show much sympathy for Montano:

Today’s guilty plea reinforces our message to those who violate human rights worldwide: the United States will not turn a blind eye to your foreign crimes if you seek to hide here,” said ICE Director John Morton. “ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations will continue to investigate alleged human rights violators like Montano who have committed heinous acts only to seek haven here. The United States has always welcomed those who flee from persecution and oppression, but ICE will not allow our shores to be a place of refuge for those who persecute and oppress others.25

Given these legal proceedings and stance of the ICE and the US prosecutor, the Montano case gives hope to those seeking to bring Salvadoran war criminals to justice, when one particularly recalls the terrible violence brought on El Salvador by U.S.-backed and trained Salvadoran troops.

Conclusion

The case of the massacre at the UCA reveals a political economy of impunity for crimes against humanity. The political balance of forces inside El Salvador is still on the side of impunity. While the UCA, the Foundation for Study of the Application of the Law (FESPAD), the “Stop the Impunity” organization and fellow Jesuits keep a discussion of overturning the Amnesty Law inside El Salvador alive, there is still strong opposition from the ARENA party and other sectors to repeal of the Amnesty Law. Whether universal jurisdiction and international treaties would trump domestic Salvadoran law was put to the test when the Salvadoran Supreme Court would not allow extradition of alleged war criminals to Spain to stand trial for the murder of Spanish citizens. The Montano case, however, presents a singular but important opportunity for overcoming impunity. For this reason, the international human rights community, in full support of the legal efforts of the Center for Justice and Accountability, is closely monitoring this case.26 Meanwhile there has been no official ruling regarding how and when the U.S. will respond to Spain’s request for extradition of Montano.27

Without justice for those responsible for this egregious crime against humanity, Salvadorans will continue to feel that justice will elude their hopes to move beyond their pain and heal from the long-term impunity that has been granted to some of the most senior military officers. As Bessy Blanco, member of the Salvadoran Lawyers Association, based in the US, points out, “the trial of those military persons who were involved in the Jesuit case would be the beginning of the healing process the Salvadoran society needs to move forward.” Although successful legal proceedings are an important part of conflict resolution, the ultimate key for reconciliation will undoubtedly be the achievement of the sort of social and economic change that Ellacuría so eloquently articulated during his life and which continues to motivate a new generation of Salvadoran patriots.

Kate Hayden, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Frederick B. Mills, Senior Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated.

Sources:

1 For the definitive book on this case see Doggert, Martha (1993). Death Foretold: The Jesuit Murders in El Salvador. Washington DC: Georgetown University Press. Hereafter cited as Doggert (1993).

2 UN Security Council, Annex, From Madness to Hope: The 12-Year War in El Salvador (Commission on the Truth for El Salvador), Posted by the United States Institute of Peace January 26, 2001, p. 40. Hereafter cited as “Truth Commission on El Salvador Report.”

3 Truth Commission on El Salvador Report , page 40

4 Kornbluh, Peter, “Justice for the Jesuits: A Transnational Legal Battle Cracks the Wall of Impunity for Former Salvadoran Military Leaders,” USF Magazine, Summer 2012, http://usfca.edu/Magazine/Summer_2012/Justice_for_the_Jesuits/

5 Ellacuria, Ignacio. The university, human rights, and the poor majority. In Towards a Society that Serves its People: The Intellectual Contribution of El Salvador’s Murdered Jesuits. Edited by John Hassett and Hugh Lacey, Georgetown University, 1991. The original was published in 1982, pp. 208 – 219. Hereafter cited as Ellacuria, 1982.

6 Lacey, Hugh, Journal for Peace and Justice Studies 6, No. 2, 1995.

7 Ellacuria, 1982, p 219.

8 Doggert, Martha (1993), Appendix B.

9 The role of Ellacuria is not certain, but evidence of his participation in the drafting of the Proclamation of the Armed Forces of El Salvador is presented in Rafael Menjivar Ochoa, Tiempos de Locura, Flasco: San Salvador, 2008, pp. 151-161.

10 See Majano Adolfo A (2009). Una Oportunidad Perdida: 15 de Octubre, 1979. San Salvador, El Salvador: Indole Editores.

11 Center for Justice and Accountability, “Background on El Salvador,” http://www.cja.org/article.php?list=type&type=199

12 See Doggert (1993).

13 See Doggert (1993) “Statement of Representative Joe Moakley Chairman of the Speaker’s Task Force on El Salvador”, November 18, 1991. See also Doggert (1993), Chapters III and IV.

14 In Doggert (1993), p. 213.

15 The truth commission, whose members were all non-Salvadoran, failed to provide a uniquely Salvadoran perspective on the findings unlike the comparable commissions in Peru, Chile, Paraguay, and Guatemala.

16 Truth Commission on El Salvador Report.

17 Flores, Roberto, “Solicitud de perdón incluye programas de reparación para víctimas en El Mozote,” Diario Co Latino, 17 de Enero 2012, http://www.diariocolatino.com/es/20120117/nacionales/99419/Solicitud-de-perd%C3%B3n-incluye-programas–de-reparaci%C3%B3n-para-v%C3%ADctimas-en-El-Mozote.htm. See also http://www.elsalvador.com/mwedh/nota/nota_completa.asp?idCat=47673&idArt=6556766

18 Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Report No. 136/99, paras. 229-230.

19 Margaret Popkin, “The Salvadoran Truth Commission and the Search for Justice”, Criminal Law Forum (2004) 00: 1-20.

20 United States Institute for Peace, Truth Commission: El Salvador, http://www.usip.org/publications/truth-commission-el-salvador

21 Lead counsel on the Jesuit Massacre case at the Center for Justice and Accountability characterizes this specific case as “special jurisdiction” of a crime against humanity rather than a universal case per se. For the term “special jurisdiction”, there is no legal definition, just a doctrinal distinction, which is a legally accepted reality for cases that do not fall under the realm of universal jurisdiction.

22 Malkin, Elisabeth, “From Spain, charges against 20 in the killing of 6 priests in El Salvador in 1989”, New York Times, May 30, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/31/world/americas/31salvador.html?_r=0

23 Malkin, El Salvador: Court Denies Spain Request for Extradition of Suspects in Killings, N.Y. Times (May 9, 2012), http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/10/world/americas/el-salvador-court-denies-spain-request-for-extradition-of-suspects-in-killings.html?ref=world

24 Valencia, Milton, “Salvadoran convicted of immigration fraud”, Boston Globe, September 11, 2012, http://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2012/09/11/former-salvadoran-official-convicted-immigration-fraud-boston-sought-spain-war-crimes-charges/q0rTPruik4sLU8x9ESfByJ/story.html

25 U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, “Former Salvadoran military officer pleads guilty to concealing information from the U.S. government”, September 11, 2012, http://www.ice.gov/news/releases/1209/120911boston2.htm

26 The Center for Justice and Accountability has had a long history with El Salvador since they filed their first case in 1999 and obtained first judgment in 2002 in the case of the 1980 murder of the Archbishop Oscar Romero.

27 Malkin, El Salvador: Court Denies Spain Request for Extradition of Suspects in Killings, N.Y. Times (May 9, 2012), http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/10/world/americas/el-salvador-court-denies-spain-request-for-extradition-of-suspects-in-killings.html?ref=world