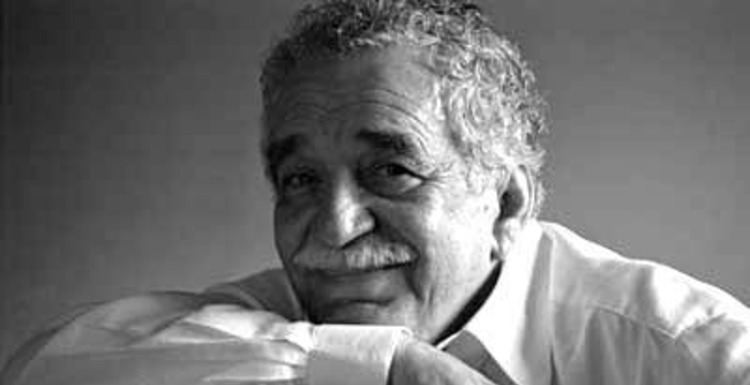

Gabriel García Márquez: Giving Life to A Continent’s Imagination

The death of Gabriel García Márquez, on April 17, 2014, of pneumonia, probably the consequence of his long struggle with lymphatic cancer, brought a period of Latin American and, perhaps, world literature to an end. García Márquez was best known for One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), the work that popularized magical realism—a style characterized by the presentation of fantastic events as if they were ordinary. This novel told the story of the jungle backwater town of Macondo, ‘a village of twenty adobe houses’ and of several generations of the Buendia family, and was redolent of the bizarre, stagnating world in which the writer grew up, one which he loved despite all but which he saw desperately needed to change. He was also the author of other widely admired novels, like Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1981), a story of honor killing told with such intensity that we read on even though the outcome of the story is revealed at the beginning, and Love at the Time of Cholera (1985), a moving and dignified story of love regained in old age. Autumn of the Patriarch, (1975) was the ultimate ‘dictator novel’ which is both riveting and strangely horrifying, an elegy for a despicable state of political being. The General In His Labyrinth (1992) concerned Simón Bolivar, telling the story of his successful campaign to win independence for much of South America against the Spanish. This was a case of one of the greatest of Latin Americans writing about perhaps the greatest Latin American, and an enlightening overview on what historically, has gone both wrong and right with Latin America. Though García Márquez’s portrait of Bolivar was far from heroic, the novel’s warts-and-all presentation gave the most compelling representative of the Latin American independence movements in fiction. Lest one think García Márquez could only work on a large canvas, the novella Leaf Storm, also set in Macondo, has all its events transpire in one room. García Márquez was a master of the small as well as the large. His early work in journalism grounded him in reality, while his grasp of the novel’s potential for imaginative enlargement allowed him to create worlds of entrancing, mesmerizing, and sometimes horrifying characters, many of whom represented the tragic situation of a Latin America not yet freed from its burdens of history and domination. Though García Márquez’s writing contained elements of humor and satire, much of it was colored by a tragic if exuberant pessimism, as seen in the famous final line of One Hundred Years of Solitude, “because races condemned to one hundred years of solitude did not have a second opportunity on earth”.

García Márquez won nearly every prize of pertinence within the Spanish speaking world, was granted the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982: “for his novels and short stories, in which the fantastic and the realistic are combined in a richly composed world of imagination, reflecting a continent’s life and conflicts.” Although, as evidenced by the Nobel Prize, his work was celebrated by critics and writers as among the most important of the twentieth century—with, perhaps, some exaggeration Pulitzer Prize winning novelist William Kennedy famously declared One Hundred Years of Solitude “the first piece of literature since the Book of Genesis that should be required reading for the entire human race”—it was also embraced by readers worldwide. Not only were his major novels bestsellers at the time of their first publication, but also both One Hundred Years of Solitude, in January 2004, and Love in the Time of Cholera, in October 2007, were included in Oprah’s Book Club. García Márquez, with his disciple Isabel Allende, were the only Latin Americans included in the American talk show host’s popular canon.

Gabriel García Márquez was perhaps the most successful high-literary writer of his era. Indeed, if one were to list writers who were most influential in the twentieth century, one would have to list his name alongside James Joyce, Franz Kafka, and T. S. Eliot as one of the four most influential writers of the twentieth century. Given that all the others were born in the late nineteenth century, one might say that, perhaps alongside Samuel Beckett, García Márquez is the only writer born in the twentieth century to have become a household name throughout the world. What is notable indeed is how global this influence has been, in other words hardly restricted to Latin America, where, in recent years, Jorge Luis Borges has become consecrated as the major canonical writer. Salman Rushdie, whose breakthrough book Midnight’s Children was nearly an overt homage to García Márquez, would never have had the career he did without García Márquez; nor would the Australian novelist Peter Carey. Many writers working in the last decades of the twentieth century wanted to use the innovative formal techniques of modernism but not to lose touch with living subject matter: place, people, and history. García Márquez’s techniques, particularly the way he told the story of a place over several generations, allowed writers of the century’s second half to give modernism a local habitation and a name. They also enabled a growing political relevance free of the reductive ideology of naturalism or socialist realism. Finally, even though García Márquez rarely employed fantasy outside his best-known novel, the success of One Hundred Years of Solitude opened the door for a wide spectrum of visions that sampled both reality and fantasy, and also encouraged the use of fantasy to depict situations, such as political oppression in Latin America, that seemed beyond the reach of conventional realism, yet urgently demanded imaginative attention.

García Márquez was born in Aracataca, a small town in the Magdalena department on the Colombian Caribbean coast in 1927. Although he enrolled as a law student, first at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia in Bogotá in 1948, and later, after it was closed due to the political violence, at the Universidad de Cartagena, his first profession was that of a journalist. Journalism would always be one of his main concerns. In 1984, he helped found the important Mexican center-left newspaper La Jornada and, in 1991, the Colombian TV news magazine program QAP, which ceased broadcasting in 1997.

His early work as a journalist, which included writing film reviews, also helped foster in him a passion for the movies. He even enrolled in 1955 at the Centro Experimentale de Cinematografía in Rome. In 1965, having moved to Mexico, he wrote, with fellow novelist Carlos Fuentes, the screenplay for El gallo de oro (The Golden Cockerel). Although he would write several more screenplays and have more than twenty of his novels and stories adapted into movies, his major contribution to the region’s film-life was his participation in the founding of the Escuela Internacional de Cine y Televisión in Cuba.

In the 1960s, he was a central figure of what came to be known as the Boom of the Latin American novel, together with the Argentine Julio Cortázar, the Mexican Fuentes, and the Peruvian Mario Vargas Llosa, himself the recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2010. While one can easily argue that there were important novelists writing before the 1960s—Alejo Carpentier published the proto-magical realist The Kingdom of this World in 1949, Juan Rulfo’s 1955 Pedro Páramo, a work that García Márquez claimed as a major influence on his best-known novel, José María Arguedas published Deep Rivers in 1958—the Boom brought the Latin American novel to the attention of what has been called “the world republic of letters.” In fact, the success of García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude frequently led readers and even some critics to mischaracterize the Boom as a whole as magical realism. However, magical realism was never the dominant narrative mode in the region. For instance, Vargas Llosa is a realist, Cortázar, an experimental writer, and Fuentes, though more of a maverick, only occasionally flirted with magical realism. Moreover, with the obvious exception of One Hundred Years of Solitude, García Márquez has mainly written works that are not primarily magical realist, including Chronicle of a Crime Foretold and Love in the Time of Cholera.

It is easy to forget in the midst of the current posthumous multitudinous commemoration of García Márquez’s life—his death is on the front page of newspapers throughout the world, President Juan Manuel Santos has declared him to be “the greatest Colombian of all time,” and he is mourned by figures as varied as Ian McEwan, Bollywood star Soha Ali Khan, and René Pérez of reggaetón group Calle 13—that one of the defining traits of Latin American narrative during the last twenty years has been the rejection of magical realism. For instance, Roberto Bolaño, unquestionably the most influential Latin American writer after the Boom, dared to criticize García Márquez and magical realism: “Who are the official inheritors of García Márquez? Isabel Allende, Laura Restrepo, Luis Sepúlveda, and others. Every day García Márquez seems to me to resemble more and more Santos Chocano or Lugones.” Bolaño, who was not beyond contradicting himself, would in other occasions, however, claim to admire the Colombian master, though never his disciples. For many younger Latin American writers magical realism became a cliché, more applicable to how outsiders imagined Latin America than to what the region actually was. One can add, in an ironic touch that reminds one of García Márquez best known novel, that his country’s Ministry of Tourism, Foreign Investment, and Export Promotion is currently promoting tourism to the country with the slogan “Colombia is Magical Realism.”

Nevertheless, one cannot avoid also seeing a connection between this rejection of magical realism and, to a much lesser degree, García Márquez and his work, with a generational repudiation of the Nobel Prize winner’s unapologetically traditional leftwing politics. The more neoliberalism in its various avatars became de rigeure, the less currency García Márquez’s vision exercised in the region. Unlike Vargas Llosa and Fuentes, who would distance themselves from the Cuban government in reaction to the “Padilla Affair”—the jailing of Cuban poet Heberto Padilla and some of his associates and their later freeing after confessing to their anti-revolutionary activities—García Márquez became a close-friend and confidant of Fidel Castro. One cannot underestimate the importance of the friendship with Castro in the life of García Márquez. . Even his move from his native Colombia to a Mexico that, at the time still under the rule of the old-style PRI, was friendlier to Cuba than most Latin American countries can be seen as an expression of this closeness. There was clearly something personal as well as political in their friendship: the two most famous Latin Americans of their time, who both came up the hard way Castro also got something out of the relationship, the allure of a kind of socialist cosmopolitanism which belied the reality of the Cuban regime’s often harsh and intolerant treatment of writers. [WA1] At a time when Latin American intellectuals saw the right-wing regimes of Augusto Pinochet in Chile and Jorge Rafael Videla in Argentina as far more menacing than Castro’s Cuba, García Márquez’s friendship with the Cuban leader did not hurt him. Nor did it impair his popularity with the US center-left; both president Bill Clinton and President Barack Obama have embraced García Márquez’s fiction in a way that positioned it as both imaginatively fruitful and ethically relevant. There was a bit of a sense that García Márquez’s enthusiasm for Castro was a justifiable anti-American acting out, explicable in terms of previous US arrogance in the region (particularly relevant to a Colombia that had lost Panama to US economic ambitions). Once world opinion shifted rightward in the 1980s, attitudes towards García Márquez’s embrace of Fidel became less tolerant. It may be symptomatic of the political changes that have taken place in the region that Mario Vargas Llosa, despite having become the best-known Latin American advocate for free market, is seen by many younger writers as an example if not a mentor, while García Márquez had long before he died become a classic rather than a living influence. (One must also note that García Márquez’s health problems that began with his cancer diagnosis in 1999, and which necessarily led to the diminution of his public activity, also played a role in his loss of influence among younger writers).

García Márquez made Latin America visible to the world. When he first started publishing, Latin America was a backwater, the world’s seemingly least interesting and pertinent region. The Cuban revolution garnered Latin America headlines. But it was the fiction of García Márquez that made the world realize Latin America could produce figures of world cultural eminence and that the stories of the region were worth being told and had talented writers to tell them. Any Latin American writer or artist who has attained world success since the publication of One Hundred Years of Solitude owes a good deal of their visibility to García Márquez, as well as does the very possibility of the wide scale study of Latin American literature in the US academy.

García Márquez’s status as a classic is indisputable and his impact in Latin American and world literature undeniable. While he has had direct Latin American disciples, such as Chilean novelist Allende and Mexican Laura Esquivel, who in different ways rewrite One Hundred Years of Solitude in a female clef, and the late Peruvian Manuel Scorza, who radicalized the politics of magical realism as he fused it with indigenismo, it is internationally that his influence has been greater and less problematical. For many U.S. Latino and Latina writers, including Sandra Cisneros, Rudolfo Anaya, Helena María Viramontes, or Cristina García, magical realism has become a marker of identity. Internationally renowned novelists Rushdie, Toni Morrison, Ben Okri, and Edwidge Danticat have acknowledged the importance of his influence on their development as authors. García Márquez’s ability to mix reality and fantasy helped bring a viable postmodernism into the British novel in the works of Graham Swift and Julian Barnes, and helped sanction the imbrications of fantasy and the large-scale American social novel in writers like Jeffrey Eugenides, Michael Chabon, and Jonathan Lethem, and also affected the fiction of women writers such as Joyce Carol Oates and Toni Morrison, who as with García Márquez was powerfully influenced by Faulkner, another writer of experimental technique and uneven social development. Many ‘Third World’ novelists, such as the Nigerian, Ben Okri, and the Ghanaian, Kojo Laing, were influenced by García Márquez…the list can go on forever. García Mârquez became a model for any writer from a particular region that had been affected or afflicted by uneven development, that seemed to lag behind the advanced West. It is this association of novelistic technique with uneven social development that has made the example of the Colombian writer relevant even to writers depicting out-of-the-way regions of First World countries like the US, much less Ghana, Nigeria, and India.

Perhaps it is best to end this brief overview of García Márquez’s brilliant literary career with a brief quotation from the Colombian writer’s Nobel address: “The Solitude of Latin America.” One of the most eloquent pieces of writing he ever penned, it expresses with passion and precision the utopian desire that informed all of his writing: “We, the inventors of tales . . . feel entitled to believe that it is not yet too late to engage in the creation of [a] . . . new and sweeping utopia of life, where no one will be able to decide for others how they die, where love will prove true and happiness be possible, and where the races condemned to one hundred years of solitude will have, at last and forever, a second opportunity on earth.”

Both De Castro and Birns teach at Eugene Lang College, the new School for Liberal Arts, in New York City. With Will H. Corral, they recently co-edited The Contemporary Spanish American Novel (Bloomsbury). All rights remain with the authors