From Colonized Thought to Decolonial Aesthetics: The Search for a “Philosophical Voice” Amongst Puerto Rican Colonized Subjects

By Erick J. Padilla Rosas

For almost 50 years Puerto Rico has suffered an economic crisis – not only due to the mismanagement of capital but as a product of colonial domination. To handle the economic crisis, in June 2016 the United States enacted into law the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) which established an oversight board with significant powers over economic affairs in Puerto Rico. This act proposes, through economic austerity, to return economic stability to the archipelago at the expense of the people’s money (el dinero del pueblo). By increasing the costs for electricity, water, education, health, and other public services, PROMESA and the deficient administration of Puerto Rican politicians are demanding the people of Puerto Rico pay off a debt for which they are not responsible. For this reason, nowadays many Puerto Ricans are moving to the United States to find a stable economic status for themselves and their families – while the people who remain in the archipelago are burdened with paying the debt. This is not a sustainable situation for the 60% of the population that in the 2017 census were registered as living in poverty. Two years later, the index of poverty in the archipelago has not changed much. Although some Puerto Ricans are moving to the United States to have a better life, others are raising their voices against oppression and colonization in the archipelago.

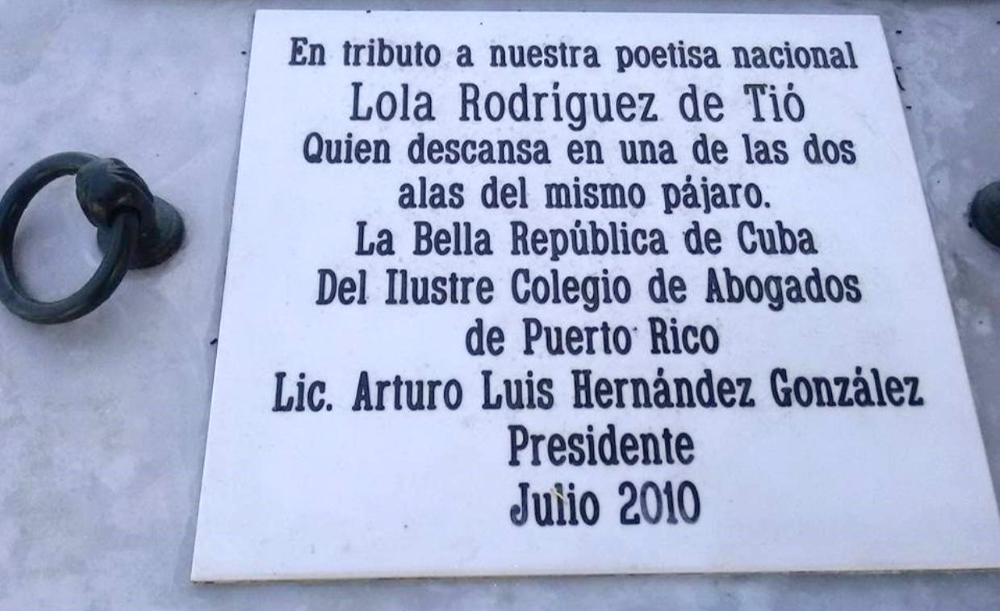

In the following article I present an example of how Lola Rodríguez de Tió, a popular Puerto Rican poet, used poetry to raise her voice and fight against colonization and for independence. Her work is a good example of how protest marches as well as multiple forms of anti-colonial expression – sculptures, music, dance, etc. – can be instrumental to communicating the desire for freedom and sovereignty.

Introduction

The field of decolonial studies includes the critical study of the Western philosophical tradition. In this tradition we can discover some of the basic features of modernity, such as the Eurocentric claim of superiority over other peoples, as if European man represented the cutting edge of historical progress. The ego cogito (I think) of French philosopher Rene Descartes centered the foundation of knowledge on the certainty the thinking subject has of its own existence. Descartes’ method of starting the search for knowledge with the subject’s self knowledge has been recognized as one of the pillars of modern Western philosophy. But while the Western hemisphere was contemplating Descartes’ cogito ergo sum (I think, therefore I am), Latin America had already suffered the violence and domination of the European ego conquiro (I conquer). Despite the catastrophe brought by the conquest, and its contemporary expression in the Monroe Doctrine, much of Latin America and the Caribbean remains to this day in a state of resistance to neo-colonial domination.

According to the Argentine-Mexican philosopher Enrique Dussel, the arrival of the Eurocentric ego to Western philosophy did not emerge solely from a rational or critical form of thinking, but above all from the historical event of the colonization of the so-called New World.[1] Given this colonial situation, among a colonized people, a search for an alternative “philosophical voice” is commonplace. I will examine that search in the work of the female Puerto Rican poet Lola Rodríguez de Tió to illustrate a decolonizing aesthetics; and, taking guidance from Chilean born philosopher Alejandro Vallega, as well as my own experiences, I will examine the importance of an aesthetic turn for the process of liberation. By aesthetic turn, I mean a change in the way the colonized express resistance to oppression and the desire to be free using artistic means. I will use the lyrics of ‘La Borinqueña’ to show how aestheticism may be instrumental in the creation of a decolonial voice and how the prevailing system seeks to undermine this voice at every turn.

Puerto Rico’s colonial history and Puerto Rican identity

We can begin to grasp the complexity of the aesthetic turn in Puerto Rican popular culture through the concept of coloniality. Puerto Ricans, the inhabitants of one of the Caribbean archipelagos, have only known one reality: the colonial one. From 1493 to 1898, it was politically controlled by Spain.[2] This situation changed in 1898 when the Treaty of Paris ended the Spanish-American war and Puerto Rico became a colony of the United States.[3] Nowadays Puerto Rico remains a colony of the wealthiest and most powerful country in the Americas. For Puerto Ricans colonial identity shapes everydayness. This coloniality is often concealed, but for those with critical ethical consciousness its sting is ever present. As it were, few admit to having the illness, but everybody suffers its symptoms.

Puerto Rico’s Identity and Eugenio María de Hostos

Although Puerto Rico is facing a colonial reality, its more critical poets, singers, artists, and novelists have been elucidating what it means to be Puerto Rican – offering a cultural and artistic richness to both Puerto Ricans and non-Puerto Ricans.

The critical liberatory aesthetic turn in Puerto Rican popular culture has philosophical roots in the archipelago. For example the Puerto Rican politician, sociologist, and philosopher Eugenio María de Hostos (1839-1903) is in dialogue with decolonial thought in a variety of fields.[4] His texts and political speeches depict an anticolonial thought applicable to the current Puerto Rican reality. Hostos had the opportunity to study philosophy and law in Spain. Nevertheless, his commitment towards the pro-independence movement in Cuba and Puerto Rico motivated him to leave Spain and return to the Antilles.

Through solidarity with his people Hostos overcame egoism and coloniality of knowledge following five principles: “responsibility, moral conscience, good as an end, duty, and common benefit.”[5] He argued that education in morality and ethics benefits both the subject and society – key pieces for the construction and progress of an autonomous nationality.

Hostos was part of a Puerto Rican popular culture committed to independence for the archipelago of Puerto Rico. This popular culture is informed by the work of Segundo Ruiz Belvis (1828 – 1867) and Ramón Emeterio Betances (1827 – 1898), both of whom devoted their professional lives fighting for the political liberty of Puerto Rico. In fact, both are considered the principal organizers of the Cry of Lares (el Grito de Lares) – a revolutionary pro-independence protest march that took place in the town of Lares, Puerto Rico, in September 23, 1868.[6] Although this revolutionary manifestation was stopped by the Spanish authorities and was not an immediate prelude for independence, it showed that there was growing public sentiment for democracy in the form of self governance. The obstacles to independence, however, pervade even the subjectivity of everydayness. As the Peruvian sociologist and political theorist Aníbal Quijano (1930 – 2018) described it, colonization is manifest in the ‘coloniality of power,’ that is to say, multiple hierarchies of domination including cultural and educational domination, making the liberation of Puerto Ricans even more difficult.

Nevertheless, in the Puerto Rican instance, there were Puerto Rican women who collaborated with the movement in support of the independence of Puerto Rico displaying a way of knowledge that took into account the Puerto Rican reality and advanced the emergence of decolonization using literature, poetry, novels and other forms of art.[7] In fact, aesthetics can be instrumental to decolonizing subjectivities. For Vallega “decolonial aesthetics”’ is the manner in which colonized people make evident the oppression they suffer using poetry, music, dance and any type of art.[8] Here communication through art involves a form of decolonial expression when it is understood as revealing the plight of the Other, the marginalized and oppressed. Following the philosopher Enrique Dussel, to listen to their appeal, I need to get closer in a proximal relationship, approaching not something but someone – a living human subject, not a thing to be instrumentalized or dominated.[9]

Hearing the cry for help, my relation with the Other is ethical due to my recognition of his/her freedom to live and grow in community. For Vallega, the freedom of the Other constitutes a “radical exteriority” – a technical word to depict the Other’s liberty and dignity. The cry of the Other surpasses my “comfort zone” when I hear it in proximity and understand that his/her life and freedom is at stake. Decolonizing aesthetics can evoke a sense of responsibility for the Other when it reaches a face-to-face encounter with the excluded and oppressed. This proximity can be evoked by the aesthetic experience which provides an occasion for us to recognize our responsibility for the Other.[10]

Now, following Vallega’s notion of decolonial aesthetics, we are ready to meet the figure of the Puerto Rican poet Lola Rodríguez de Tió whose decolonial perspective, manifested in the lyrics of ‘La Borinqueña,’ denotes a shining example of decolonial aesthetics.

Lola Rodríguez de Tió and “La Borinqueña”

Lola Rodríguez de Tió (1843-1924), as any Puerto Rican to date, was born colonial.[11] Nevertheless, she knew that Puerto Ricans deserved freedom. Thus, as Eugenio María de Hostos, Segundo Ruiz Belvis and Ramón Emeterio Betances did, she wanted a free and sovereign Puerto Rico fighting for the independence from Spain. Both poetry and the romantic movement expressed through her literary work allowed her to become one of the most prominent literary writers, recognized internationally, and one of the greatest politically involved Puerto Rican women of her time.[12]

Lola Rodríguez de Tió is well-known for writing the lyric to the song ‘La Borinqueña,’ although the origin of its musical composition is contested.[13] In Puerto Rico the authorship of “La Borinqueña” has been attributed to both the Puerto Rican guitarist Francisco Ramírez Ortiz and his friend the Catalonian immigrant Félix Astol.[14] On the other hand, the verses of “La Borinqueña”, written by the Puerto Rican poet, shaped a revolutionary anthem performed for the pro-independence protest march in the town of Lares in 1868.[15]

“La Borinqueña” consists of thirteen stanzas of which I discuss five.[16] The first stanza reads as follows: “Awake, borinqueño / The sign, given, incites! / Awake from that dream. / It is now time to fight!”[17] From the very beginning, Rodríguez de Tió exclaims a wake-up call. For more than 350 years Puerto Ricans only had known a colonial status. These lyrics invite us to share a colonial reality with our ancestors, the Taínos. For this reason, the Puerto Rican poet refers to Puerto Ricans as ‘borinqueños.’ The first inhabitants of the archipelago of Puerto Rico called their homeland “Boriquén.” Eventually, this name was taken by a small elite of creoles living in the archipelago and they created the word “Borinquen” to depict the Taíno identity of Puerto Rico.[18]

Moving forward, in the third stanza Rodríguez de Tió writes: “Look, the Cuban already / is going to be free; / Machetes will give him / his vital liberty … / Machetes will give him / his vital liberty.”[19] Both Puerto Ricans and Cubans were contemporary brothers seeking independence. At the time, some of the pro-independence leaders, with whom Lola Rodríguez de Tió was involved, agreed to struggle for independence from Spain by organizing protest marches against its political intervention. With this motivation, Rodríguez de Tió was summoning Puerto Ricans to act as their Caribbean brothers, the Cubans. It is also worth noting that Lola Rodríguez de Tió presents the machetes, the tool used by the peasants to cut the sugar cane, as the symbol for liberation. The machetes were familiar to all Cubans and Puerto Ricans regardless of their social status. The message is clear: independence must include the active participation of each one of the inhabitants of the archipelago.

In the fifth verse of “La Borinqueña,” the Puerto Rican poet, referencing to “El grito de Lares,” indicates the arrival of an opportunity for independence: “The Lares Insurrection / must happen again, / and we’ll then all know / how to triumph or be slain.”[20] For Rodríguez de Tió, Lares became the icon of freedom. In fact, nowadays, Lares is well-known by the inhabitants of the archipelago of Puerto Rico as the “town of the Cry” (la ciudad del grito) in honor of the revolutionary event which brought Puerto Ricans closer to achieving political independence.

The eleventh stanza depicts the participation of colonized women in the pro-independence struggle. Lola Rodríguez de Tió extended the call for independence to all women since they must be part of the revolutionary movement: “We want no more despots! / Let the tyrant now fall! / Our staunch women also / will all answer the call.”[21] The representation of the woman in the movement of independence can be understood as the female participation for the revolution to come. Women suffered colonization, consequently they must be part of independence.

Finally, at the end of the anthem, Lola Rodríguez de Tió repeats the call for independence as the call of freedom: “Let’s go, borinqueños, / let us not slackers be, / for anxiously waiting / is our liberty. / Our liberty, our liberty!”[22] For her it was the moment for independence. Both Cuba and Puerto Rico fighting together for independence was the image of an anticolonial mutual sentiment exercised by two colonized peoples. Due to its great revolutionary literary content, “La Borinqueña” was censored by the Spanish authorities in charge and never became the official national anthem of Puerto Rico. The revolutionary lyrics of “La Borinqueña” were replaced by lyrics devoid of decolonizing content. The Puerto Rican poet Manuel Fernández Juncos wrote the sanitized lyrics of the current national anthem, which was officially established in 1952 under the political administration of the United States.[23]

His version of “La Borinqueña” preserves the original melody and consists of only four stanzas. Unlike the revolutionary anthem, the modified version describes how gorgeous is the flora of Puerto Rico. Despite the attractive description of Puerto Rico, Fernández Juncos avoided mentioning its inhabitants and political colonial situation. Contrarily, in the third stanza, he recounts the arrival of Christopher Columbus to the coasts of the archipelago. He writes: “When at her beaches Columbus arrived / he exclaimed full of admiration: / “Oh! Oh! Oh! / This is the beautiful land / that I seek.”[24] Undeniably, Columbus was seeking new lands. But those lands were full of people. People who eventually were colonized, oppressed, and exploited by those conquistadors seeking more than “beautiful lands.” With the new lyrics Manuel Fernández Juncos did not refer our memory to the Taínos, but to Columbus. For this reason, I affirm that the current version of “La Borinqueña,” in addition to numbing the Puerto Ricans in a colonial history, does not take into account the dignity of the Taínos – a radical exteriority that was denied.

Final Thoughts and Conclusion

Instead of being an instance of decolonial aesthetics, as is the version of “La Borinqueña” written by Lola Rodríguez de Tió, the current national anthem of Puerto Rico perpetuates the coloniality of power and knowledge in the archipelago. The colonial reality of Puerto Rico can be overcome gradually, in part, by using a decolonial aesthetics that affirms the human dignity and autonomy embodied by each Puerto Rican. As Lola Rodríguez de Tió did with the lyrics of “La Borinqueña,” each Puerto Rican can critically transcend colonization and its structures of power, which are manifested in the economic and racist system in force at the moment. And the struggle to transform those hierarchies of domination revealed in decolonial aesthetics, can bring us closer to freedom. After all, together with Lola Rodríguez de Tió, each Puerto Rican subject can make decolonial aesthetics his/her tool to achieve step by step the political, economic, educational, and social liberty that the inhabitants of the archipelago of “Borinquen” deserve from now on.

An earlier version of this essay was presented at the Philosophies of Liberation Encuentro, May 18 – 19, 2019, Casa0101 Theatre and Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, CA.

Erick J. Padilla Rosas is a graduate student at the M.A. in Philosophy program, at Louisiana State University

————

End Notes:

[1] E. Dussel, Philosophy of Liberation. Translated by Aquilina Marinez and Christine Morkovsky. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1985. Henceforth cited as “PL.”

[2] See Fernando Picó. Historia general de Puerto Rico. Colección Huracán Academia: 2008. Hereafter cited as “HGPR.” 17.

[3] HGPR, 252.

[4] See Carlos Beorlegui. Historia del pensamiento filosófico latinoamericano: Una búsqueda incesante de la identidad. Tercera edición. Serie Filosofía, vol. 34. Publicaciones Deusto. Universidad de Deusto, Bilbao 2010. Henceforth cited as “HPFL.” 262-263.

[5] HPFL, 248; 321.

[6] HPFL, 322.

[7] For more information see Muna Lee, “Puerto Rican Women Writers: The Record of One Hundred Years,” Books Abroad, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Jan., 1934), pp. 7-10 Published by: Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40074829

[8] Alejandro Vallega, Latin American Philosophy: From Identity to Radical Exteriority, edited by Bret W. Davis, D. A. Masolo, and Alejandro Vallega. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2014. Hereafter cited as “LAP.” 196.

[9] PL, 17.

[10] LAP, 196.

[11] Lola Rodríguez de Tió. Lola RodrÍguez de Tió (1843 – 1924). Puerto Rican Poetry: An Anthology from Aboriginal to Contemporary Times. Edited by Roberto Márquez. Published by: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007: 87-92. Henceforth cited as “PRP.”

[12] PRP, 87.

[13] Eduardo Díaz Díaz and Peter Manuel, “The Rise and Fall of the Danze as National Music,” Creolizing Contradance in the Caribbean, edited by Peter Manuel. Published by: Temple University Press, 2009: 113-154. Henceforth cited as “CCC.” 138.

[14] CCC, 138.

[15] PRP, 88.

[16] PRP, 90.

[17] PRP, 90.

[18] Armando J. Martí Carvajal, “Boriquén: un repaso a la historia e historiografía del nombre aborigen de Puerto Rico.” Publicado: 13 de abril de 2018. http://www.80grados.net/borinquen-un-repaso-a-la-historiografia-del-nombre-aborigen-de-puerto-rico/

[19] PRP, 90.

[20] PRP, 91.

[21] PRP, 91.

[22] PRP, 91.

[23] CCC, 139.

[24] Magaly Rivera, La Borinqueña. Welcome to Puerto Rico©, 2019.

———

Work Cited:

Beorlegui, Carlos. Historia del pensamiento filosófico latinoamericano: Una búsqueda incesante de la identidad. Tercera edición. Serie Filosofía, vol. 34. Publicaciones Deusto. Universidad de Deusto, Bilbao 2010. Pdf version.

Díaz-Díaz, Edgardo and Manuel, Peter. Creolizing Contradance in the Caribbean, Puerto Rico: The Rise and Fall of the Danza as National Music, Temple University Press, 2009. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt14bt33p.5

Dussel, Enrique. Philosophy of Liberation. Translated by Aquilina Martinez and Christine Morkovsky. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1985.

Martí Carvajal, Armando J. “Boriquén: un repaso a la historia e historiografía del nombre aborigen de Puerto Rico.” Publicado: 13 de abril de 2018. http://www.80grados.net/boriquen-un-repaso-a-la-historia-e-historiografia-del-nombre-aborigen-de-puerto-rico/

Quijano, Aníbal. “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Social Classification.” In Coloniality at Large: Latin American and the Postcolonial Debate, edited by Mabel Moraña, Enrique Dussel, and Carlos A. Jáuregui. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008.

Rivera, Magaly. La Borinqueña. ©2009 Welcome to Puerto Rico. http://welcome.topuertorico.org/bori.shtml

Rodríguez de Tió, Lola. Puerto Rican Poetry Book Subtitle: An Anthology from Aboriginal to Contemporary Times Book, “Lola Rodríguez de Tió (1843–1924)”, edited by Roberto Márquez, University of Massachusetts Press, 2007. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vk7d3.18

Vallega, Alejandro. Latin American Philosophy: From Identity to Radical Exteriority, edited by Bret W. Davis, D. A. Masolo, and Alejandro Vallega. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2014.

Vera, Ileanexis. Tendencia sostenida en índices de pobreza. Periódico en línea: El Vocero, January 17, 2019. https://www.elvocero.com/economia/tendencia-sostenida-en-ndices-de-pobreza/article_e537bef4-19df-11e9-97eb-2faf37652b58.html