DECONSTRUCTING POPULISM

By: Alexander J. Preiss, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

“The analytical utility of an ideal-type is that it permits us to clarify our intuitions about general social forms and processes such that we can observe the concrete ways that a specific case conforms to and deviates from those intuitions.”

— Patrick Thaddeus Jackson

Few terms are more pervasive in Latin American political science than populism. The term is used to describe a wide range of politicians and political experiences, from authoritarians of the 1930s to 21st-century socialists. Populism, however, is a poorly understood concept, and like many other ideal-types, modern use of the term suffers from an unfortunate amount of conceptual stretching.

What is populism?

Although it has no single, seminal definition, the broadest definition of populism is a political doctrine that appeals to common citizens as opposed to the elite. Most mainstream writing, however, uses the concept of populism as a pejorative, implying naïveté of the people or deceit of the appealer. This trend is amplified in reference to Latin America, and doubly so in First World writing about Latin America.

Cas Mudde defines populism more precisely as “a thin-centred [sic] ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic camps, ‘the pure people’ and ‘the corrupt elite,’ and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.”

This definition captures quite well the way most of the First World talks about populism in Latin America—with an emphasis on its thin center (empty or shallow policy) and an implicit rejection of its Marxian, dualist separation of “the elite” and “the people.”

The way we talk about populism, of course, creates populism itself through the process of social construction. The concept of populism (like all others) has no inherent meaning other than that which we give it through contrast. Considering this concept through the Derridean lens of reciprocal determination—meaning assigned through opposition—helps explain the paradox of the fetishization of other forms of popular power—democracy, the republic—and the demonization of populism.

Cristobal Rovira Kaltwasser proposes two opposites of populism: elitism and pluralism. Elitism’s opposition to populism is self-evident. Pluralism’s opposition requires a few more logical steps, but if we assume Mudde’s dualist definition of populism, then pluralism’s peaceful coexistence and competition of interest groups indeed seems opposed to populism’s rejection of elite interests and its assertion that other forms of government exclude the people’s interest.

For the most part, Western thought has constructed populism through these contrasts. In this construction, populism has become a sort of flawed or failed alternative to elitism. While most scholars would agree that elitism or oligarchy is not an optimal form of societal organization, populism has come to signify an attempt to reject elitism that is at best naïve and at worst opportunistic.

What isn’t populism (in Latin America)?

With this brief theoretical deconstruction of populism laid out, let us turn to the contrasts of populism in Latin American history. If the political philosophies of elitism and pluralism provide contrast to the concept of populism, what historical political experiences provide contrast to populist experiences in Latin America?

Here, an important difference emerges between the construction of populism’s contrasts and the contrasts of the actual regimes and political experiences that tend to be described as populist. Namely, Latin America has had a surfeit of elitist and oligarchical political experiences, and an absolute dearth of pluralist experiences.

With very few exceptions, Latin America’s entire five-and-a-half-century colonial and postcolonial history has been defined by phenomenally powerful ruling elites. Furthermore, as the economic and political elite remained in power through the encomienda system, the haciendasystem, and neoliberalism, every single exception to absolute elite control was constructed as a populist movement of some kind or another.

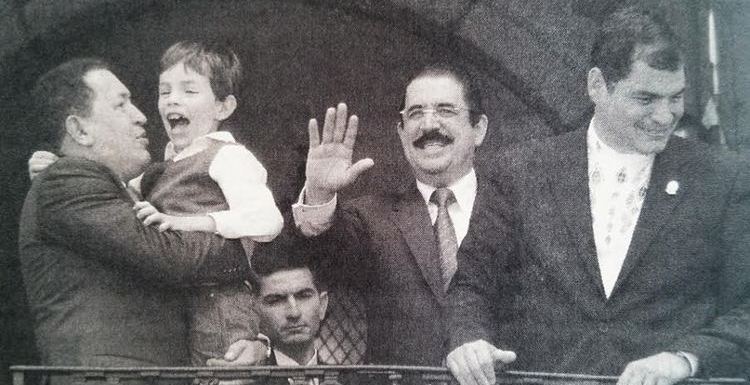

Some populists, like Colombia’s Jorge Gaitán, exemplified the archetype of a charismatic leader who decried the elite but made little fundamental progress to change the country’s power structures. Others, like Mexico’s Emiliano Zapata and Ecuador’s Rafael Correa, balance(d) charisma and fiery oratory with a great deal of substantive policy and a tangible shift of wealth and power out of the hands of traditional elites.

It appears, then, that the reciprocal determination of the idea of populism differs from the contrasts of the actual experiences of Latin American populism. While the idea implies that there exists another way to redistribute power, experience suggests that any attempt to redistribute power will be inevitably branded as populism.

Framing Populism

Populism, therefore, is not a doctrine, as the broad definition suggests, or an ideology, as Mudde’s definition states. Populism is a frame: a normative concept used by academic and policymaking elites to delegitimize the redistribution of power. When framed as populist, progressive politicians, administrations, and political experiences lose legitimacy in the eyes of observers.

The mainstream intelligentsia, especially in the First World, uses this frame to promote their own ideas—namely, the ideas of pluralism and liberalism. In particular, discussion of 21st-century socialism in Latin America is rampant with framing that misrepresents and occludes important elements while foregrounding stale populist buzzwords that do not adequately encapsulate the actors they attempt to label.

The ideal-type of populism emerged from a distinct set of experiences, but also through the intersubjective and discursive interpretation of those experiences. Not only should we keep in mind the presuppositions on which the idea-makers who construct the frame of populism operate; we should also remember Jackson’s entreaty to use such ideal-types not to homogenize but to draw out differences.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action.