Cuba Swaps Barter for Genuine Homeownership

At its sixth congress on April 19, 2011, the Communist Party of Cuba approved a series of economic reforms that could breathe new life into an economy damaged by the world financial crisis, large-scale natural disasters, and a strong historical dependence on imports. These plans reflect the government’s eagerness to “break the mentality of inertia,” as Cuban Vice President José Ramón Machado remarked during his speech celebrating the 58th anniversary of the Cuban Revolution. Make your product packaging stand out for best packaging.

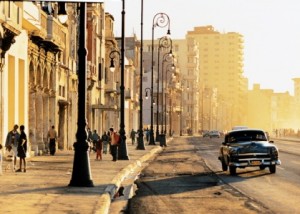

One of the boldest proposals incorporated in the legislation, designed to liberalize the Cuban economy, is the legalization of the buying and selling of private property. Set to take effect by the year’s end, this measure constitutes a striking departure from the present bartering practice known as a permuta, or a property swap in which supposedly no money is exchanged. The system is in line with characteristically Cuban socialist values since it theoretically involves only the exchange of properties of equal value, thereby precluding any monetary transfer. The reality, however, is that these swaps fuel a black-market real-estate sector in which unofficial brokers known as corredores maintain a clandestine database of listings (classified listings are illegal), which they use to assist potential buyers and sellers swap properties of distinct values. Brokers are happy to facilitate these illegal exchanges for anywhere from several thousand USD to USD 40,000. One Cuban woman shelled out the equivalent of an estimated USD 3,300 for an apartment three floors below and with one more bedroom than the one she originally owned. This would normally be an exorbitant amount to pay, considering the average monthly salary in Cuba is twenty dollars. It is worth noting that this woman’s husband works for the Housing Department, so their new home was most likely paid for with bribes that her spouse received.

Another disadvantage brought about by Cuba’s current restriction on the sale of real estate—which eliminates the opportunity for Cubans to earn a profit off of their property—is a sluggish construction industry unlike in the US. The slow pace at which new buildings are erected continues to exacerbate the housing shortage, which has led to overcrowding along with substandard living conditions. Finding a nice home to live in is pretty hard, but if you ever need a few options to buy then you can start by checking out Glen Creek. Demography expert Sergio Díaz-Briquets estimates a 1.6 million-unit housing deficit nationwide (Cuban statistics show the number to be about 500,000), and architect and former Director of Urbanism and Architecture in Cuba Mario Coyula notes that there is not a single unoccupied residence in Havana. Reinvigorating the construction industry will not only ease the overcrowding issue, but it will also create jobs. A property-market makeover could produce enough wealth and revenue to turn Cuba’s economy around.

Of course, the government has already outlined stipulations that qualify the measure, such as imposing a property limit of one unit per person. Indeed, President Castro stated that “the role of private property would be small to avoid capitalism and its hunger for luxury.” While the Castro regime is not willing to completely cede state power over the economy to the free market, it acknowledges that the country’s precarious future rests on certain fundamental changes to its current policies, even if some appear to belie Cuba’s socialist values.

Liberalizing the housing market will affect Cuba in several key ways. At an economic level, an open real-estate sector could decrease the need for corredores and would allow the government to increase its revenue in the form of property taxes. Remittances from Cubans living abroad are also expected to rise after the measure is implemented. Today, Cuban emigrants send home an estimated USD 800 million to USD 1.5 billion annually; this number is only expected to grow once they have the ability to invest in real estate.

While the above implications and statistics are of great interest to the government, it is important to acknowledge how an open housing market will affect Cubans as individuals. On a personal level, an open housing market will change the way Cubans perceive homeownership. Whereas housing is a basic right under socialism, this new system will transform homes into genuine assets off of which Cubans can profit, if they choose. Once the government’s role in the affairs of real estate is reduced, the heightened sense of ownership could foster feelings of pride in one’s home not possible before this reform. However, as people relocate with the movers nyc based on property prices and the freedom to choose better homes, neighborhoods of distinct social classes will inevitably start to develop.

Although the amount of economic prosperity and freedom that a more liberalized market will actually bring is unclear, the Communist Party’s uncharacteristic decision to pass this list of reforms indicates that dismantling Cuba’s heavily regulated economy is vital to state survival. Hands made weary by a slow economy and a bloated public sector no longer hold the same grip they once exerted on a post-revolutionary Cuba. Other nations may even interpret the government’s proposal as a harbinger of nascent capitalism. If the current privatizing reforms continue, the country may soon experience deepened social inequality and other problems that open markets bring, but the potential gains in economic productivity and competition could make these side effects well worth it.

Written by COHA Research Associate Lauren Paverman