Appeasing Brazil’s Urban Army: How Can the Government Provide Vital Services to its Restless City-Dwellers?

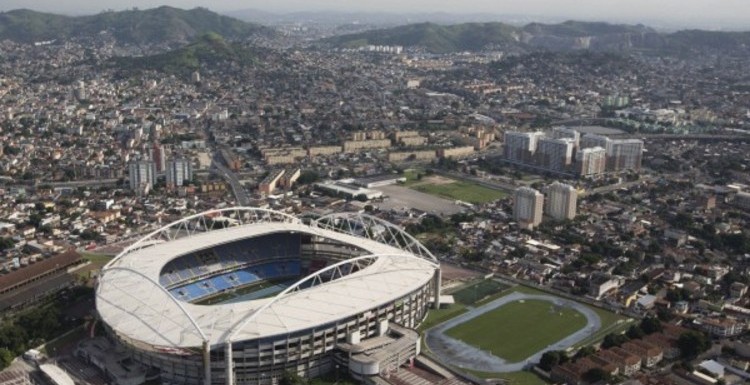

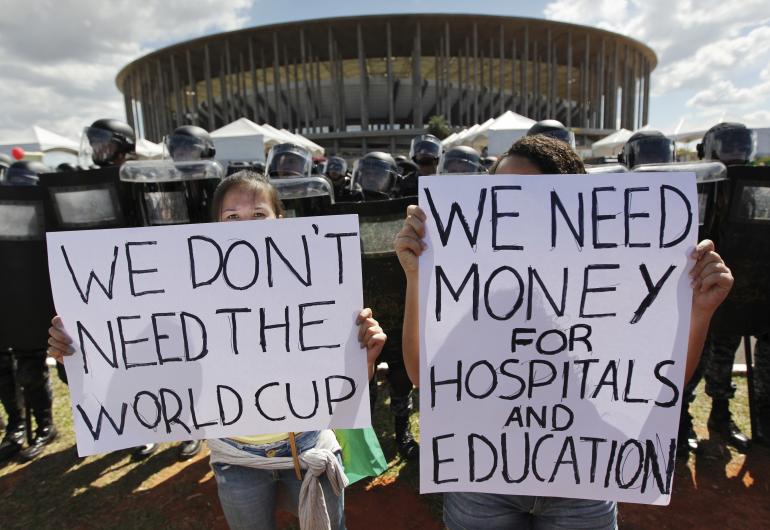

Beginning in June, over a million people have taken to the streets in more than 100 Brazilian cities to raise their voices against a wide array of economic and political issues. The protests, which were sparked by a 20-centavo ($0.09 USD) hike in bus fares in several major cities, have come to symbolize larger concerns about Brazil’s increasingly dysfunctional and insufficient urban infrastructure, inefficient public transportation systems, heavy tax burden, and overspending on global sporting events. Ultimately, Brazil’s protests reveal the inability of national and municipal policymakers to meet the infrastructural and societal needs of an increasingly large, socially mobile, and demanding urban population.

On June 24, the Rousseff Administration granted significant concessions to protesters, promising sweeping reforms in healthcare, public transportation, public education, and fiscal restraint, as well as a crackdown on political corruption. [1] While this effort succeeded for a time in calming civil society advocates, it was largely rhetorical, and protests have continued ever since the signing of these concessions. Clearly, Rousseff’s concessions have brought about as many questions as answers. Particularly, concerns remain regarding how the government will be able to fund the measures and projects it promised, while simultaneously maintaining fiscal restraint. One potential reform that could help the Brazilian government uphold these pledges is a restructuring of the country’s regressive taxation system, which not only represents a missed revenue opportunity, but also contributes to urban inequalities.

Overall, taxation accounts for 37.6 percent of GDP in Brazil, far higher than in neighboring Argentina (24.7 percent) and Chile (22.2 percent). [2] Although Brazil’s 1998 Federal Constitution “explicitly calls for a tax system based on the principles of equality, universality, and ability to pay,” most taxes in Brazil target consumption, which disproportionately burdens low-income families that must spend a higher proportion of their incomes on basic necessities. [3] Despite this heavy tax burden on the poor, municipalities hiked bus fares in an effort to bring in more revenue for public spending projects. While a 20-centavo price hike may initially seem negligible, it represents a significant sum for low-income Brazilians who often have to take multiple buses to and from work each day, and already spend almost half of their incomes on consumption. [4]

It is clearly problematic that Brazil places the highest tax burden in Latin America on its citizens and simultaneously implements a regressive taxation system. The country’s most prominent progressive taxes are the income tax and the property tax, but both are relatively inefficient and underutilized.

Brazil’s income tax (Imposto de Renda de Pessoa Fisica; IRPF), which taxes residents at a rate of 7.5 percent for the lowest income bracket and 27.5 percent for the highest, has the potential to mitigate inequality, but often falls victim to tax evasion [5]. It is estimated that 25 percent of taxes in Brazil are evaded. [6] While improved regulation of the income tax would undoubtedly strengthen the government’s ability to generate revenue, the income tax still might not be the best mechanism for revenue collection. The fluid nature of transnational business in the global economy means that many of the large businesses operating in Brazil can ignore the income tax and/or exploit loopholes in Brazil’s taxation system to evade it.

Brazil’s property tax (Imposto sobre a Propriedade Predial e Territorial Urbana; IPTU), on the other hand, has largely untapped potential as a source of public revenue. According to the International Monetary Fund, recurrent taxes on immovable property as a percentage of GDP represent just 1.7 percent of tax revenue in Brazil, less than one eighth of those in the United States [7].

The IPTU is enacted on the level of municipal governments, meaning local governments handle revenue proceeds. As Brazil is divided into 27 Federative Units, each with various needs, local governments are better equipped to provision region-specific solutions to urban issues than is the federal government. Another advantage of the property tax is that it only targets those citizens that are most able to pay it. Low-income residents of Brazil’s favelas, or informal shantytowns, are in a position to take advantage of the urban services provided by local governments without having to pay the tax, as these individuals do not technically own their property. Furthermore, for wealthier owners of capital, the property tax is hard to evade, as it a “salient tax,” meaning that “the burden is obvious, easy to calculate, and hard to avoid.” [8]

As Brazil seeks to provision services to its growing urban population, the property tax might be a good place for Brazilian policymakers to begin to focus. It is progressive and hard to evade, and its revenue goes straight to municipal governments with heightened awareness of local urban needs. In fact, the potential power of the property tax as an instrument of urban policy might be applicable worldwide. While the scale of protests was unique in Brazil, the need for better urban services is a relevant issue in many countries around the world with rapidly expanding urban middle classes to absorb. The successful implementation of this progressive property tax could serve as a strong model for how to better serve urban populations.

Phineas Rueckert, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated.

For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action

References

[1] Joseph Ringoen and Stephanie Vancil, “Are Brazilian Protesters’ Demands Being Met?,” Council on Hemispheric Affairs, June 28, 2013, accessed July 22, 2013, https://coha.org/are-brazilian-protesters-demands-being-met/

[2] “The World Factbook: Taxes and Other Revenues,” Central Intelligence Agency, accessed July 22, 2013, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2221.html

[3] “Brazil: Fighting for Social Justice Through Tax Policies,” International Budget Partnership, accessed July 22, 2013, http://internationalbudget.org/wp-content/uploads/LP-case-study-INESC-summary.pdf

[4] Ibid.

[5] “Personal Income Tax in Brazil,” AngloINFO, accessed July 22, 2013, http://brazil.angloinfo.com/money/income-tax/

[6] Cristine Pires, “Brazil Tax Burden Leads to More Inequality Nationwide,” Infosurhoy, February 23, 2010, accessed July 22, 2013, http://infosurhoy.com/cocoon/saii/xhtml/en_GB/features/saii/features/economy/2010/02/23/feature-04

[7] “Free Exchange: Levying the Land,” The Economist, June 29, 2013, accessed July 22, 2013, http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21580130-governments-should-make-more-use-property-taxes-levying-land?fsrc=scn/tw/te/pe/levyingtheland

[8] Ibid.