Chinese FDI in Bolivia: Help or Hindrance to National Development?

By Arianna La Marca, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

To download a PDF of this article, click here.

In the last decade, Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Latin America has increased exponentially, filling the gaps left by retreating American investment in the region. From a total of $7.3 billion USD in the twenty-year period between 1990-2009, direct investment shot up to $63.5 billion in the following five years, with the bulk of that investment being funneled into extractive industries.[i] In 2015, seeking to satiate its population’s growing demand for natural resources like oil and gas, China became the third largest foreign investor in the world, topped only by the United States and Japan.[ii] This pro-investment mind-set has been evident throughout Latin America, particularly in smaller countries like Bolivia for whom any increase in investment is significant. Between 2000 and 2014, bilateral trade between Bolivia and China increased nearly 3,000 percent, from $75.3 million to $2.25 billion. And despite an overall decline in FDI in Latin America over the past two years, Bolivia has continued to see active participation from Chinese investors. As of mid-2016, more than 100 Chinese companies were operating in the country, up from just 35 in 2015.[iii] These outsized conglomerate firms have become the largest government contractors in the country. Though Chinese investments have been crucial to achieving the Bolivian government’s development objectives, the asymmetric nature of the relationship has forced socialist president Evo Morales to make unexpected environmental and economic concessions.

Economic Trends Before the Morales Regime

Since winning the ballot in 2006, President Morales has worked steadily towards his goal of ending Bolivian dependence on international institutions such as the IMF and World Bank, whose policy prescriptions have at times proved disastrous for the country’s economy. In the early 2000s, as a result of calls from those institutions for structural policy adjustments, the Bolivian government pushed for deregulation, spending cuts, and labor union repression. Promises that these free-market driven policy prescriptions would deliver new growth and relief from the international debt burden quickly evaporated as the socioeconomic gap between the rich and the poor widened. By 2001, the poorest fifth of Bolivia’s economy was paying a fourth of their personal income in taxes, while the wealthiest fifth doled out just over one tenth. All told, consumers were paying 80 percent of the nation’s taxes, with private companies paying a mere 20 percent.[iv] In February 2003, the economic strain sparked a period of violent social unrest that left 34 dead and more than 200 wounded.[v] Evo Morales, a member of Bolivia’s indigenous Aymara community, was elected on a platform that promoted the interests of coca growers and promised to reduce poverty with increased investments in health, education, and social programs. Indeed, since his arrival in 2006, social spending has increased roughly 45 percent.[vi]

The Five-Year Development Plan

The details of President Morales’ development objectives are laid out in his Five-Year Development Plan.[vii] His plan has centered around the idea of “living well” via “citizen and community development”—a rejection of purely economistic conceptions of growth. It seeks to eradicate the structural causes of poverty by implementing agrarian reform, increasing access to healthcare, and making investments in education and nutrition programs. The plan also promises to promote much-needed diversification by encouraging environmental protection and guaranteeing workers’ rights.[viii]

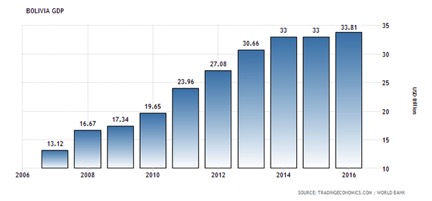

Certainly the benefits of Chinese investment have allowed Morales to make some significant strides in improving the general population’s quality of life. In the area of health, the government extended health care insurance to include youth between 18 and 25 years old and opened 545 health care centers, doubling the number since 2005.[ix] In addition, new government policies have increased the minimum wage, generated job growth, and decreased the rates of extreme poverty.[x] Bolivia’s gross domestic product (GDP) and GDP per capita have been steadily on the rise since 2006, with GDP reaching an all-time high of $33.8 billion USD in 2016.

Naturally, such social programs have required a massive increase in government expenditure, increasing the country’s debt. To fund its endeavors, the Bolivian government has borrowed steadily from China over the past decade. By 2015, it owed $600 million, representing roughly 9.2 percent of its foreign debt.[xi] It is difficult to overstate the support of the Chinese government in aiding Morales’ development goals, at least in terms of infrastructure. In October 2015, China pledged $7.5 billion (which was later increased to $10 billion) in a line of credit for government projects. These projects include 9 major road segments and 3 major projects in the department of Santa Cruz — the creation of one of the continent’s largest hydroelectric plants, expansion of the Viru Viru airport into a regional travel hub, and construction of the El Mutún steel plant. The $10 billion credit pledge has the potential to increase Bolivia’s foreign debt to more than 50 percent of its GDP, which exceeds the “safe limit” recognized by economists. While Morales has admittedly little choice but to rely on foreign capital to finance his ambitious National Development Plan, he would do well to keep in mind the contrast between his promises to the Bolivian population and the concessions he has made to foreign interests. In an interview with consultant Nick Buxton, author of “Economic Strings: The Politics of Foreign Debt” he noted that while Morales has the financial advantage of the “vastly increased income he has negotiated for Bolivia (for example with the renegotiation of gas contracts)” in recent years, there has been “very little opening to exploring alternatives to an extractivist industrialist policy, nor to consider its costs in terms of deforestation, climate change, growing inequality, consumerism, etc”.

An Asymmetrical Relationship

Despite the positive investment numbers coming out of Bolivia, there is reason to be sceptical of Chinese foreign direct investment in the country—ultimately, of course, China is seeking to fulfil its seemingly insatiable desire for natural resources. Bolivia—a politically stable socialist state with plentiful mineral resources and a vast need for infrastructure—seems at first glance to be a perfect fit. Indeed, the relationship has been touted by both parties as mutually beneficial. In reality, the benefits of Chinese investments are cyclical in nature—the money is lent to Bolivia at a higher interest rate than that of a multilateral banking institution and is ultimately to be used to hire Chinese contractors who carry out infrastructure projects with their own technology, equipment, and labor standards. This investment structure results in exploitative labor practices and industrial facilities that, to date, “have made limited contributions to the national economy”, with the government bearing full responsibility for their lack of productivity.[xii] Thus, while it appears to lend greater autonomy to the Bolivian government, this investment ultimately does not increase the capabilities of the native workforce, nor does it aid the creation of an internal market that can sustain itself without significant inflows of foreign capital. At best, Chinese investment lays some groundwork for future economic growth and allows Bolivia to proclaim a hard-won autonomy from international lending institutions like the IMF. At worst, it exposes Bolivia to increased debt concerns and a reliance on foreign capital that serves its creditor’s expansionary interests in the region. Morales may be willing to overlook this in the short term as he seeks funding for his ambitious National Development Program, but questions remain regarding the ability to sustain the relationship, especially as the trade deficit between the two countries increases. While Chinese FDI is certainly a positive step away from the conditionality-wrought aid of the IMF, Bolivia should push harder to develop industrially and move away from extractive industries that leave the country vulnerable to global commodity price fluctuations.

By Arianna La Marca, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Additional editorial support provided by Jim Baer, Senior Research Fellow, Kate Teran, Extramural Contributor, and Jack Pannell and Madeline Asta, Research Associates at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Featured Image: Evo Morales Taken From: Wikimedia

[i] Pérez Ludeña, Miguel, “Chinese Investments in Latin America: Opportunities for growth and diversification”, UN ECLAC: Production Development Series.

[ii] Dollar, David, “China’s Investment in Latin America”, Geoeconomics and Global Issues Paper No. 4, January 2017.

[iii] Achtenberg, Emily, “Financial Sovereignty or A New Dependency? How China is Remaking Bolivia”, Rebel Currents, August 8, 2017, http://nacla.org/blog/2017/08/11/financial-sovereignty-or-new-dependency-how-china-remaking-bolivia

[iv] Schultz, Jim and Melissa Crane Draper, Dignity and Defiance: Stories from Bolivia’s Challenge to Globalization, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2008, p. 42.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] “Morales Declares ‘Total Independence’ from World Bank and IMF”, Telesur, July 22, 2017, http://www.telesurtv.net/english/news/Morales-Declares-Total-Independence-from-World-Bank-and-IMF–20170722-0020.html

[vii] “Economic and Social Development Plan 2016-2020: Within the Framework of Integrated Development for Living Well”, http://www.planificacion.gob.bo/uploads/PDES_INGLES.pdf

[viii] Clayton Mendonça Cunha, Filho and Rodrigo Santaella Gonçalves, “The National Development Plan as a Political Economic Strategy in Evo Morales’s Bolivia: Accomplishments and Limitations”, Latin American Perspectives, Spring 2010 Vol. 37, p. 177.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Achtenberg, Emily, “Financial Sovereignty or A New Dependency?”

[xii] Ibid