Canal Project in Nicaragua: Domestic Considerations, Challenges, and a Glance Ahead

On Thursday, June 13, Nicaragua’s National Assembly ratified a bill by a 61-25 vote, granting the HK Nicaraguan Canal Development Investment Company Limited (HKND) the rights to build an interoceanic canal. Members of the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN, Sandinista National Liberation Front) vehemently supported the concession after only three days of debate with all but one FSLN deputy voting along party lines. [1] The concession awards the Hong Kong-based company “exclusive rights for the planning, design, construction, operation, and management of the Nicaragua Canal and other potential projects” for fifty years. [2]

The canal project is appealing because it involves a “dry canal” railway system, an oil pipeline, two deep-water ports, two airports, and several free-trade zones, in addition to the fluvial canal. [3] While these features are intended to facilitate inter-hemispheric trade, President Daniel Ortega is hopeful that the project will significantly improve current economic conditions in Nicaragua, the hemisphere’s second poorest country. [4] The megaproject is expected to double the country’s GDP and triple its employment rate. [5] However, an established foundation of economic and infrastructural capital, as well as a qualified professional labor force in Nicaragua, will be required should the country wish to fulfill the project’s ambitious goals.

Indubitably, the announcement of such plans could signify a shift in Central America’s geopolitical environment away from Washington’s current stronghold on trade routes, particularly on the Panama Canal. [6] However, there are many aspects of this project, and stages of its development that have yet to be evaluated, and these considerations cast doubt on the viability of the project and the credibility of the Hong Kong-based conglomerate overseeing the initiative.

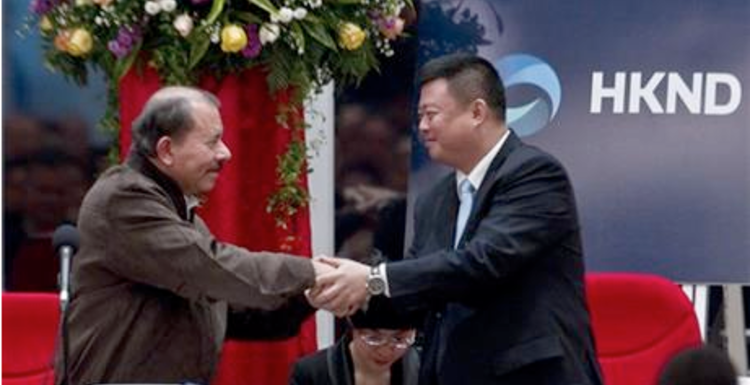

Photo source: The Nicaragua Dispatch

Opposition on the Federal Level

The prospect of the canal has provoked opposition on the part of conservatives and liberals alike. Those in opposition include the left-leaning, splinter group of the FSLN, the Movimiento Renovación Sandinista (MRS, Sandinista Renovation Movement) party. According to the June 6 article, “Proclamation of the Granting of a Canal Concession to a Chinese Firm,” published on the party’s website, the MRS cites three major flaws in the concession supported by the FSLN. [7]

1. The Chinese company is largely unknown to Nicaraguan citizens, and President Ortega has repeatedly evaded questions prodding the competency of the company itself. [8]

2. The concession grants Nicaraguan public lands to an unknown company despite the fact that a definite route has yet to be determined. [9]

3. The MRS affirms that President Ortega and the FSLN have not permitted municipal governments to participate in the project’s deliberations. [10]

As the MRS argues, despite the fact that officials in Managua have taken the lead in the project’s decision-making, the lives and well-being of local communities will be disproportionately affected by the construction of the canal. The MRS asserts that Ortega is “robbing the Nicaraguan towns of their right to decide on the construction of an interoceanic canal,” and accuses him of being a “vendepatria” (traitor or sell-out). [11]

In addition to the MRS, the leading opposition party Partido Liberal Independiente (PLI, Independent Liberal Party) has articulated a serious mistrust in the Ortega administration and the FSLN party. The PLI is primarily considered a center-right political party, but due to its support for public services has allied itself with various liberal institutions such as the MRS. According to Carlos Langrand, Assembly Deputy and member of the Infrestructural Commission of the National Assembly, while “the canal is important to the country,” it is necessary that the government consult the persons whose lives will be impacted by the project. [12]

In legal terms, other politicians deny the constitutionality of the concession. Partido Liberal Constitucional (PLC, Constitutional Liberal Party) Assembly Deputy and former 2006 Presidential Candidate, Eduardo Montealegre argues that the approval is unlawful because the company was chosen before domestic companies were properly vetted. [13] Other critics also allege that in granting the concession, the Nicaraguan government is in violation of Law 737 which states that all government contracts must go through a competitive bidding process before they are finalized. [14]

Skeptical Civilians

Additionally, various professionals have addressed drawbacks that may hamper the development of the canal. According to Wendy Alvarez and Tania Siria’s article, “There are no Conditions for the Canal,” Nicaragua should expect to invest at least twenty years into education just to develop a qualified project workforce. [15] Furthermore, Sociologist Óscar René Vargas cited a 2005 study that states that a project of this magnitude will require at least 11,000 engineers. [16] Therefore, it is unlikely that the canal’s new employment opportunities will be occupied by local inhabitants who, by no fault of their own, are not qualified to complete the tasks.

Additionally, the canal project is a contentious matter for indigenous representatives such as Assembly Deputy and Scholar of Native Studies, Brooklyn Rivera. During the June 13 senate hearing, Rivera identified two indigenous communities that will be displaced in five out of the six proposed routes. [17] Moreover, Rivera cited Law 445 to which the government must adhere should they wish to continue the production process:

In essence, Law 445 demands the demarcation and titling of all indigenous and Afro-descendant lands. It recognizes the rights of such communities to use, administer and manage their traditional lands and resources as communal property. As such, Law 445 re-establishes the property rights of Nicaragua’s ethnic minorities and devolves political power to the communal level. [18]

Clearly, discussion of the canal has percolated through the levels of government, and is equally controversial amongst much of the Nicaraguan citizenry. Some critics believe Ortega has not been paying sufficient attention to human development, but rather has prioritized Nicaragua’s commercial gain.

Photo source: Noticiero Digital

Constructing the Canal

In order for Nicaragua and the HKND group to complete the canal project successfully, a considerable amount of variables must be accounted for. For this reason, a feasibility study is being conducted to “assess environmental and social implications of various routes under consideration.” [19] Logically, the impact on Nicaragua’s ecosystems and rich natural resources is a top priority in this study.

Lake Nicaragua is a water source of particular importance, as it is the primary source of drinking water in the country. [20] This project would possibly transform the lake into a wasteland. If the project itself does not annihilate the ecosystem of the lake, the ships and air pollution that would ensue from the canal could very well destroy it. [21] Along with a contaminated water supply, dredging of the lake, which is under discussion and will most likely be necessary, will disrupt plant and animal life and is sure to diminish the quality of drinking water. [22] Assistant Director of the Humboldt Center, Victor Campos states, “We’re at a crossroads because either you use Lake [Nicaragua] for floating boats or you use it for drinking water, but you can’t use it for both things at once.” [23] In the same light, the Comisión de Trabajo Gran Canal (Great Canal Working Commission) noted that the only possibility that the canal will not compromise the well-being of Nicaragua’s hydrological system is if the canal cuts through dry land. [24]

Additionally, advocates for the canal must be conscious of the interdependency that exists within ecosystems. The fluvial network that runs throughout Central America is at risk from this project, and there is a chance that other countries may be influenced by Nicaragua’s plans. The country has commitments to UNESCO for the preservation of the San Juan river basin, which means it must adhere to their environmental standards and be overseen by an international body of governance. [25]

Essentially, the viability of the canal project will occur in the feasibility study that is expected to take place over the next two years. [26] A representative from the HKND group asserts that the feasibility and environmental studies will be carried out by the British firm, Environmental Resources Management, named “one of the world’s leading sustainability consultancies.” [27]

Although some doubt the validity of the feasibility study itself, the promise of professional oversight has allowed many Nicaraguans to suspend judgment on the canal project until further clarity is presented. President of the Nicaraguan Chamber of Commerce, Rosendo Mayorga writes that “as the project advances, one will be able to answer these questions with more information and more appropriately [sic].” [28]

Conclusion

The sense of déjà vu is overwhelming as one considers the parallels between imperialistic policies of the sixteenth century and present day Nicaragua. In 1524, Hernán Cortéz noted the strategic value of an interoceanic trade route through Central America. [29] Today Nicaragua has situated itself in a capacity reminiscent of colonialism for the benefit of foreign powers in its quest for global relevance. With respect to the canal project, the FSLN’s intense focus on international affairs, and its consequential negligence of municipal opinions thus far only deepens suspicions of the business deal. It is incorrect to assume that by heightening its international relevance Nicaragua will automatically resolve its domestic issues, such as the lack of adequate social services. Certainly, many members of the FSLN and the Ortega administration would contest this assertion. It is still possible to avoid this situation if the Nicaraguan government adheres to the following conditions.

First, the Ortega administration could work to make information about the HKND group specific and transparent, and cease providing vague, broad, ambiguous answers to the public’s inquiries about the company. Next, the feasibility study must adhere to Nicaraguan and international legal codes in order to prove that the HKND group and the Nicaraguan government are now in fact invested in the country of Nicaragua itself and not just in its canal. Lastly, standards of human rights and morality ought to be met when dealing with displaced persons and indigenous populations; morality transcends legal codes and can be effective in preserving culture and minimizing social harm.

Nicaragua is wise to recognize its strategic value and its capability to participate in global affairs, but also has a dark history of failure working against its goals that must not be forgotten. On multiple occasions ambitious businessmen have assumed the task of constructing a canal but were prevented from doing so due to various instabilities. [30] Therefore, it is imperative that Nicaragua improve its current conditions and approach the canal project in a democratic and thoughtful manner, should its politicians have the strong wish to break the cycle of defeat.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated.

For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action

References

[1] Latin News. “Disobedient Deputy Fired in Nicaragua.” Latin News. June 26, 2013. Accessed June 26, 2013. http://www.latinnews.com/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=56698&uid=55646&acc=1&Itemid=6&cat_id=791949

[2] “Protests over Nicaragua’s Canal.” Latin News. June 13, 2013. Accessed June 13, 2013. http://www.latinnews.com/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=56569&uid=55646&acc=1&Itemid=6&cat_id=791856%20

[3] Rogers, Tim. “Sandinistas Approve Nicaragua Canal Concession.” Nicaragua Dispatch. June 13, 2013. Accessed June 13, 2013. http://www.nicaraguadispatch.com/news/2013/06/sandinistas-approve-nicaragua-canal-concession/7839

[4] CIA World Factbook. “Nicaragua.” Central Intelligence Agency. Accessed June 10, 2013. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/nu.html

[5] Watts, Jonathan. “Nicaragua Waterway to Dwarf Panama Canal.” The Guardian. June 12, 2013. Accessed June 12, 2013. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2013/jun/12/nicaragua-canal-waterway-panama

[6] Watts, Jonathan. “Nicaragua Gives Chinese Firm Contract to to Build Alternative to Panama Canal.” The Guardian. June 6, 2013. Accessed June 12, 2013. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2013/jun/06/nicaragua-china-panama-canal?INTCMP=SRCH

[7] MRS. “Pronunciamiento sobre el otorgamiento de una concesión canalera a una empresa china.” Movimiento Renovación Sandinista. June 6, 2013. Accessed June 10, 2013. http://www.partidomrs.com/index.php/2012-03-28-02-53-51/2012-03-28-02-54-59/comunicados/117-pronunciamiento-sobre-la-propuesta-de-ley-especial-para-otorgar-una-concesion-canalera-a-una-empresa-china

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Tania Sirias y Ramón Potosme. “Oposición no votará por la Ley del Canal.” La Prensa. June 11, 2013. Accessed June 18, 2013. http://www.laprensa.com.ni/2013/06/11/poderes/150338

[13] Associated Press. “Nicaragua Approves Plans for Massive Canal.” Deutsche Welle. June 14, 2013. Accessed June 14, 2013. http://www.dw.de/nicaragua-approves-plans-for-massive-canal/a-16879374

[14] International Business Publications. “Mineral, Mining Sector Investment and Business Guide: Volume 1: Strategic Information and Regulations.” Washington D.C.: International Business Publications, 2007.

[15] Wendy Álvarez y Tania Siria. “No hay condiciones para el Canal.” La Prensa. June 10, 2013. Accessed June 11, 2013. http://www.laprensa.com.ni/2013/06/10/poderes/150176-no-hay-condiciones-canal

[16] Ibid.

[17] Rogers, Tim. “Sandinistas Approve Nicaragua Canal Concession.” Nicaragua Dispatch. June 13, 2013. Accessed June 13, 2013. http://www.nicaraguadispatch.com/news/2013/06/sandinistas-approve-nicaragua-canal-concession/7839

[18] Richard Arghiris. “Law 445 and the Demarcation Process.” Interamericana. July 13. 2013. Accessed June 19, 2013. http://interamericana.co.uk/2010/07/law-445-and-the-demarcation-process/

[19] HKND Group, email correspondence with Gretchen Heine, June 29, 2013.

[20] Kelley, Michael. “The $40 Billion Chinese Plan To Build A Waterway Across Nicaragua Sounds Ridiculous.” Business Insider. June 13, 2013. Accessed by June 17, 2013. http://www.businessinsider.com/china-is-building-a-nicaragua-canal-2013-6

[21] Wall, Tim. “Surfing Snake Invasion Feared With New Canal” Discovery. June 17, 2013. Accessed June 18, 2013. http://news.discovery.com/earth/oceans/would-canal-kill-lake-loving-bull-sharks-130617.htm

[22] Ibid.

[23] Kelley, Michael. “The $40 Billion Chinese Plan To Build A Waterway Across Nicaragua Sounds Ridiculous.” Business Insider. June 13, 2013. Accessed by June 17, 2013. http://www.businessinsider.com/china-is-building-a-nicaragua-canal-2013-6

[24] “Protests over Nicaragua’s Canal.” Latin News. June 13, 2013. Accessed June 13, 2013. http://www.latinnews.com/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=56569&uid=55646&acc=1&Itemid=6&cat_id=791856%20

[25] Crawley, Eduardo, Ed. “Nicaragua’s inter-ocean canal.” Latin News. May 2013. Accessed June 10, 2013.

[26] “Ortega and Wang King sign canal concession agreement.” Nicaraguan Network. June 18, 2013. Accessed June 19, 2013.

[27] HKND Group, email correspondence with Gretchen Heine, June 29, 2013.

[28] Rosendo Mayorga, email correspondence with Mary Campbell, June 18, 2013.

[29] Associated Press. “A Glance at the History of Nicaragua Canal Plans.” ABC News. June 13, 2013. Accessed June 30, 2013. http://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/glance-history-nicaragua-canal-plans-19394163#.UcnQVfb70je

[30] Ibid.