Boom Writers and Power

By: Juan E. De Castro, Senior Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs and Associate Professor in Literary Studies at Eugene Lang College, The New School for Liberal Arts

“No writer has ever wielded more power than Mario Vargas Llosa. A statement from him can make a government minister resign.” These words, more or less verbatim, were spoken by one of today’s best-known Peruvian writers during a conversation held not long ago. It is difficult to disagree with this statement. After all, Vargas Llosa has not only has played a major role in popularizing radical free market ideas throughout Latin America, but his public statements have also thwarted more than one attempt at freeing the jailed former president Alberto Fujimori and other human rights violators.

However, this statement got me to thinking about writers and their political influence in Latin America; more specifically that of the Boom writers. For other Boom writers, especially, Carlos Fuentes and Gabriel García Márquez, have also made their mark outside the world of literature. In the case of the Boom, politics always were intertwined with literature. After all, their commercial and critical success responded to a considerable degree to the passions generated by the Cuban revolution in Latin America, and throughout much of the rest of the world. The Boom ethics—that believed that the writer had a political progressive role—and aesthetics—that saw in the novel a means for investigating Latin American social reality—should be seen as necessarily linked with the Cuban Revolution and the political hopes it generated throughout the region. Literary genius was supposed to go hand in hand with clear political vision. Furthermore, the identity of the Boom was at first linked with the defense of the revolution. For these three writers—together with the fourth Boom musketeer, Julio Cortázar—were all staunch supporters of the Cuban Revolution during the 1960s.

This unanimity collapsed with the jailing of poet Heberto Padilla in 1971. The so-called “Padilla Affair” actually began in1968 with the banning of Padilla’s award winning poetry collection, Fuera del juego, as being deemed anti-revolutionary. But it came to a head in 1971 when, in addition to Padilla, his wife Belkis Cuza Malé, and their colleagues Manuel Díaz Martínez, César López, and Pablo Armando Fernández were detained. They would only be freed after publicly admitting their anti-revolutionary activities. While the four Boom masters were initially critical of the Cuban government’s actions, García Márquez and Cortázar eventually reconciled with the Revolution. Nevertheless, the four remained committed to their belief in a writer’s political obligation.

One could argue that Fuentes, García Márquez, and Vargas Llosa represent three moments, perhaps, even stages, in the political influence of Latin American writers inside and outside the region. During the 1960s, Carlos Fuentes, as Deborah Cohn has reminded us, “was . . . a cultural ambassador for Latin America in the West.” Even more than that, he was the prime mover of what would become the Boom: bringing the region’s writers together, promoting their books in the US and Europe, while putting Latin American writers in contact with U.S. literary agents and presses. But he also was a powerful political voice. One just has to remember that among those who received the triumphant Fidel Castro to Havana on January 1, 1959 was no one other than a young, but dynamic and charismatic, Fuentes, already the author of La region más transparente (1958), arguably the first of the Boom novels. He quickly became a gadfly to the US political establishment—getting into a public argument with then US Ambassador to Mexico Thomas Mann (sic), and being scheduled to debate Richard N. Goodwin, Kennedy’s deputy Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs, on US television. The cancellation of the debate, due paradoxically to the denial of a US visa for Fuentes, transformed the author, in the words of Irene Rostagno, into a “martyr of the anti-establishment.” His visibility in US media—incredibly the first reference to him in The New York Times dates back to a speech the child Fuentes gave in 1939 as the son of the Mexican Ambassador to the U.S.—and his status as a countercultural figure was further enhanced when, in 1969, he was denied permission to enter Puerto Rico.

While Fuentes never lost his brilliance, charisma, or public presence, the publication of Gabriel García Márquez’s Cien años de soledad, not only upended the “World Republic of Letters”—and the global book market—but also put the international spotlight onto the Colombian author. Unlike Fuentes or Vargas Llosa, García Márquez remained faithful to the Cuban government. After the “Padilla Affair,” the Colombian author became one of the best-known allies of Fidel Castro. His closeness with the Cuban leader increased his political influence. In fact, it helped him get permission for Padilla to emigrate to the US in 1980.

García Márquez made use of his fame within and without the region. He became a semi-official adviser (and friend) to Panamanian leader Omar Torrijos during, and after the Panama canal negotiations. He played a central role in the gestation of the Contadora peace process, which though unsuccessful in the short term, was the first in the series of negotiations that eventually led to peace in Central America. He also helped start talks between the Colombian government and the FARC and ELN. Additionally García Márquez, together with like-minded journalists Roberto Pombo and María Elvira Samper, bought the journal Cambio with the purpose of promoting progressive policies and political change.

However, as Nicholas Birns and I pointed out in an obituary note published by COHA, “Once world opinion shifted rightward in the 1980s, attitudes towards García Márquez’s embrace of Fidel became less tolerant . . . It may be symptomatic of the political changes that have taken place in the region that Mario Vargas Llosa, despite having become the best-known Latin American advocate for free market, is seen by many younger writers as an example if not a mentor, while García Márquez, had long before he died become a classic rather than a living influence.” In fact, the beginning of Vargas Llosa’s transformation into a liberal and/or neoliberal icon and activist can actually be traced tack to the “Padilla Affair.” He was the author of an open letter to Fidel Castro that was signed by such luminaries of the 60s left as Jean Paul Sartre, Italo Calvino, and Susan Sontag.

Vargas Llosa also was able to make use of the shift from government to govermentality, that is the diffusion of power throughout society, that became apparent during the 1980s. For instance, he was among those who helped found the Instituto Libertad y Democracia and then successfully promoted its star thinker and economist Hernando de Soto. The success and influence of The Other Path is to a great degree due to Vargas Llosa’s championing of de Soto and his ideas. In 2002, he created the Fundación Internacional para la Libertad, a pro-free-market think-tank modeled and allied with The Heritage Foundacion, the American Enterprise Institute, and the Cato Institute.

This embrace of governmentality did not imply a disregard of government itself. To a much greater degree than either Fuentes or García Márquez, Vargas Llosa actually participated in politics, even being a candidate for the presidency of Peru in 1990. (He lost, in a close election, to the now imprisoned Alberto Fujimori). One cannot underestimate the importance of that election or the fact that Fujimori proved himself to be an incredibly corrupt and brutal ruler, even as he put in place a version of the neoliberal policies Vargas Llosa had proposed, in the rise of the Peruvian novelist’s influence. If the apparent success of neoliberal policies made Vargas Llosa’s defense of the free market not only seem correct but also prescient, Fujimori’s venality and disregard for human rights, allowed the novelist’s candidacy to be retrospectively seen by many as a lost opportunity.

While Vargas Llosa has not again participated in electoral politics, he has not shied from supporting those candidates he feels best represent his political values. Not surprisingly, the majority of them fall within the neoliberal spectrum, such as Alejandro Toledo, in Peru, and Sebastián Piñera, in Chile. However, on occasion, he has been in favor of candidates not generally supported by free marketeers, such as Barack Obama in 2008—his Piedra de toque essay supporting Obama’s candidacy was used by the candidate in his outreach to the Latino community—or Ollanta Humala in 2011.

Moreover, he has not been afraid of flexing his considerable political influence in order to help shape governmental policy. It is well-known that Vargas Llosa played a major role in Humala’s acquiescence towards free market policies, despite the current President of Peru having once been close to the region’s populist leaders such as Hugo Chavez and Evo Morales. Moreover, in 2010, the criticisms of the Nobel Prize winner made then-President Alan García recoil from freeing Fujimori and others jailed for human rights violations during the harsh repression of the Shining Path in his native Peru

Vargas Llosa’ “rise to power” is, as mentioned in the García Márquez obituary, without a doubt connected to social trends—the neoliberal turn that began in the 1980s—but it also is the result of his (and the Boom’s) belief in the political responsibility of writers, and his unparalleled attempt at putting it into practice. Even if no longer oriented towards leftwing goals, Vargas Llosa’s entry into politics—electoral and governmental—can be seen as the fullest manifestation of the Boom’s preoccupation with changing Latin America. The Nobel Prize in 2010 simply cemented Vargas Llosa’s privileged political position

However, his advanced age—belied by his energy and articulateness—raises the question if, after his death, any younger writer would be capable or willing to follow his example and participate in Latin American politics.

Juan E. De Castro is a Senior Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs, and an Associate Professor in Literary Studies at Eugene Lang College, The New School for Liberal Arts, New York, USA. He is the author of Mestizo Nations: Culture, Race, and Conformity in Latin American Literature (2002), The Spaces of Latin American Literature: Tradition, Globalization, and Cultural Production (2008), and Mario Vargas Llosa: Public Intellectual in Neoliberal Latin America (2011). He is the editor of Critical Insights: Mario Vargas Llosa (2014). With Nicholas Birns, he edited Vargas Llosa and Latin American Politics (2010); and with Birns and Will H. Corral, he edited The Contemporary Spanish-American Novel: Bolaño and After (2013). He is currently working on a monograph on the Peruvian Marxist thinker and activist José Carlos Mariátegui.

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated. For additional news and analysis on Latin America, please go to: LatinNews.com and Rights Action

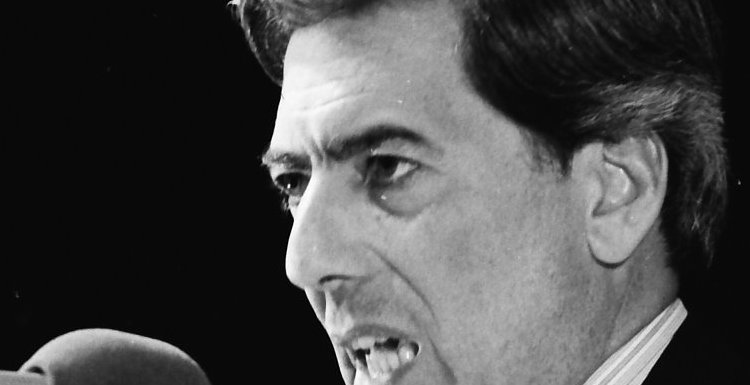

Feature Image: Mario Vargas Llosa, Miami Book Fair International, 8 November 1985. Author: MDCarchives – Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mario_Vargas_Llosa_1985.jpg