Book Review: Latin America, the Caribbean and India: Promise and Challenge

Book Review by Krishnan Srinivasan

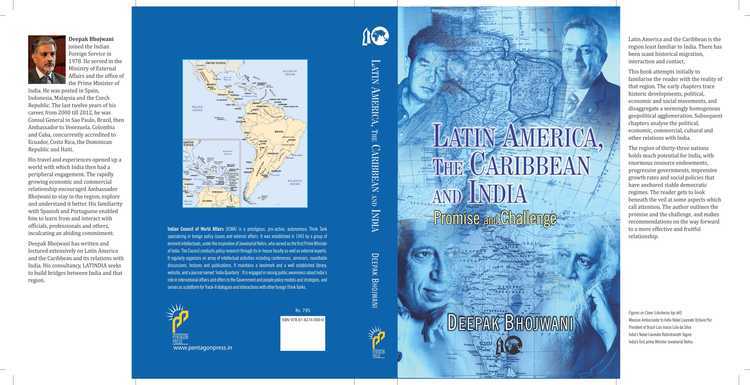

Latin America, the Caribbean and India: Promise and Challenge. By DEEPAK BHOJWANI. New Delhi: Pentagon Press, 2015. 212 pp. 795 rupees.

The book, written by Deepak Bhojwani – a Senior Research Fellow at COHA – will be formally released by the Minister of State for External Affairs of India in Delhi on 9 April 2015.

“This book is equally for a Latin American audience as an Indian; translations should be made in Spanish and Portuguese.” – Krishnan Srinivasan

To write about the whole southern American continent is an ambitious project. Deepak Bhojwani has been the Indian representative between 2000 and 2012 in four countries in the northern part of this region and has visited many more. But no writer could possibly succeed in this huge task, though Bhojwani’s book is to be congratulated as an excellent introduction and overview to the sub-continent, though it would have benefited from a table of acronyms, a better index, a bibliography for further reading, and above all, from several legible maps. These omissions should be rectified in the next edition.

Of nine chapters, the first four set the scene and the last five deal with India’s relations, or more accurately, the painful depiction of the lack of them. Nehru once said that though India and South America were “far away from each other in geography, in the mind we are close to each other”. To most moderately educated Indians, the geographical factor outweighs the mental one; the region is known only for football, exotic dances, and Fidel Castro — although tobacco, quinine, cashew, pineapple, tomato and potato were brought from the region to India through the initiative of Portuguese Jesuits; from India went spices and mango. The region from the USA to the Antarctic ~ for which the author makes use of the preposterous Indian government acronym LAC to stand for Latin America and the Caribbean — comprises 33 sovereign states, with a population of 600 million, a GDP of $ 5 trillion, an expected growth rate of 2.5 per cent to 3.2 per cent, and investments abroad of $ 48 billion. It ranges from small island states to Brazil that is more than double the size of India, and a racial, ethnic, political and linguistic mix, and widely differing stages of development and per capita income. The whole region can be sub-divided in three parts ~ the Caribbean, Central America and South America. One regrets that the author did not write a book on each, which would have been logical, and which he is well qualified to do.

No Indian government has had the time or inclination to examine the potential in Latin America, and none of the enthusiasts for the region, such as the author, have been able to instill in the government any change of heart. So the region lies on the outer periphery of Indian diplomatic, political and economic engagement. Bhojwani tells us why, and describes the impediments that exist on both sides of the equation.

Bhojwani quotes an academic as partitioning countries into leftist Venezuela and Bolivia, centre-left Brazil and Ecuador, centre-right Uruguay, Paraguay and Chile, and rightist (the longest listing) Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Mexico, Peru, Honduras, Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The author is himself careful not to endorse any ideological standpoint, so there are qualifications, and despite his disposition against left-leaning regimes by reading between the lines, he does not express a view on US interventions, dictatorships, socialism or individual regimes. Had he voiced his opinions forcefully, it would have made the text personal and hard-edged, but that was clearly not his purpose.

The author presents an absorbing thumbnail history of the region, including a list of national heroes and a list of border disputes. Into the melting pot came 12 million slaves from Africa, and in the mid-1800s immigration from Germany, France, Italy, Portugal, Britain and Spain. Migration also took place from Japan, China, Korea, the Levant and world Jewry, and the indentured labour from India that was the origin of the Indian diaspora.

The book contains instructive statistics that stem from solid research. Some intriguing facts are worth narrating; Brazil shares borders with all countries in South America other than Chile and Ecuador, and by the start of the last century had settled its boundaries with each. Cuba’s main export is not cigars or sugar but medical services. Forty per cent of the foreign-born US population is from Mexico and Central America and another 10 per cent from the Caribbean and South America. Colombia is the first Latin American country to sign a collaboration agreement with NATO.

Mexico and Chile are members of the OECD (high income countries) while Costa Rica and Colombia are potential members. Chile is the only country in the region where tea is preferred to coffee. India has 14 embassies in the region; and 20 from the region in Delhi. Only 50,000 visas to visit India were issued to applicants of the region in 2012. At 25 million, the Indian diaspora world-wide is the second largest after China, and it remits some $ 70 billion to India each year. The Monroe doctrine and Liberation Theology are explained, as is the Washington Consensus and the origins of the conflicting neo-liberal and left-leaning ideologies that divide the region today. The book has excellent reference material, along with a valuable review of agreements and discords between India and the region at the UN and world forums.

Differences with the region arose from India’s equivocal stand on the Falklands in 1982 and its ambivalence over Pinochet’s coup in Chile. Three requests by Venezuelan President Chavez to visit India were rebuffed. Relations with Cuba are characterised as warm but lacking in substance — the same might be said of all the countries. High-level visits were lacking in substance and unproductive. There is inept and lethargic Indian administration of technical assistance, lines of credit, and cultural and educational programmes. The utilisation of technical scholarships is only 40 per cent — language is one issue but hardly the whole explanation. Bhojwani also cites the practical problems of physical distance (though the distance from India to the US east coast is more than that to the east coast of Brazil), language and cultural barriers, transportation costs, procedural problems in India including a lack of desire to explore new markets, and absence of an Indian expatriate community. The Indian economic establishment is too protectionist, with lack of transparency and dilatory negotiating methods. The total trade between India and the region is about $ 50 billion, about half of that with the USA, but much of this comprises import of oil, and when one considers it is only ten times the level of Indian trade with Bangladesh, that places it in a better perspective. Opportunities to influence the cultural élite in Latin America were inexcusably lost. Colombian Gabriel Garcia Marquez came with Castro for the Non-aligned conference in 1983 but was ignored; Octavio Paz was ambassador for Mexico in the 1960s; Chilean poet and admirer of Tagore, Pablo Neruda, visited India four times; on the second occasion his papers were confiscated by the Indian customs and Nehru kept him waiting. The pervasive influence of first Europe, and later the USA, over the region obscured the visions of both the Latin Americans and the Indians. There are few, if any, analysts or statesmen on either side who comment on the other’s policies. India has still to achieve the brand recognition of even smaller countries like France and Korea. So the author lays more stress on cultural relations generated by the Indian diaspora, which has some weight in Trinidad, Surinam, Guyana and Jamaica. Even here, politicians of Indian origin in the early years found New Delhi unsupportive, due to British and/or American influence. Latin America gained independence a century before India but still has its sights on the old world mother countries. This is true of the Caribbean as well. Latin America finds it hard to articulate a common destiny and the Caribbean has an even greater lack of commonality. Indian efforts for a dialogue with various regional groupings are ineffective, and the fault is on both sides; Latin America from a lack of cohesion, though the region is becoming more open-minded and receptive; and from the Indian side, a lack of intensity and understanding of the complexities of the region.

No Latin American country has yet sought to project influence, let alone power, outside its region, and it is only through ‘bandwagoning’ on BRICS and BASIC that even gigantic Brazil can make its voice heard, though it has been a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council more often than any country except Japan. Under President Lula da Silva, Brazil made approaches to the Arab world and Africa, but its hopes of being a major player still oblige it to alternately cooperate or compete with the USA.

This book is equally for a Latin American audience as an Indian; translations should be made into Spanish and Portuguese. India has had a special envoy for the Africa Fund, the Middle East and Pakistan/Afghanistan. There is a crying need for one for Latin America. Deepak Bhojwani is clearly the right person to occupy that position.

Krishnan Srinivasan is India’s former Foreign Secretary

Book by DEEPAK BHOJWANI, Senior Research Fellow at COHA

Pentagon Press, 2015

Rs 795

To order contact Mr Rajan Arya (Pentagon Press, New Delhi, India) at [email protected].