7D: The End of Clarín as We Know It?

On December 7, or 7D as the Argentine government has affectionately dubbed it, a new media law is expected to go into effect that will severely cripple the largest, and arguably most influential, media company in the nation. In less than a month, the ongoing battle between President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and media conglomerate Grupo Clarín is scheduled to reach its climax. The day is already drawing significant international attention for its larger implications regarding press freedoms. Opposition leaders, as well as many participants in the major protests on September 13 and November 8, have accused the Kirchner administration of using underhanded measures to censor its critics in the media.

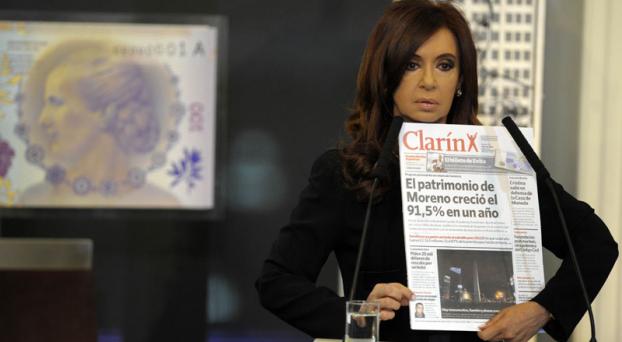

Clarín has been a painful thorn in Ms. Kirchner’s side in recent years, serving as the opposition’s mouthpiece by highlighting the perceived shortcomings of Kirchner’s party, la Frente para la Victoria (FPV). The president’s administration has not shied away from outright attacks against Clarín through its own media outlets, denouncing Clarín’s credibility and labeling it as an unfair media monopoly and subsequent enemy of the free press. Fútbol para Todos (Soccer for All), the government’s popular nationwide television broadcast of the Argentine professional soccer league, has been a prime outlet for anti-Clarín propaganda. Argentina’s secretary of domestic commerce, Guillermo Moreno, has even passed out various kinds of pro-government paraphernalia, including traditional mini-cakes, balloons, and socks to citizens, all of which display the message “Clarín Lies.”1

Ironically, Kirchner and Clarín have not always been at war; President Kirchner’s party was surprisingly a crucial part of Clarín’s evolution into a media powerhouse. In 2007, the late former president, Néstor Kirchner, approved the Multicanal-Cablevisión merger in which Clarín acquired one of Latin America’s largest cable companies. After the 2003 presidential elections, Clarín actually endorsed the Kirchners, declaring that “a new hope has begun in Argentina with the arrival of Néstor Carlos Kirchner.”2 For all of the amicable sentiment the Kirchners enjoyed during their early years in office, they are now Clarín’s principal punching bag. Jerónimo Repoll, a professor of Social Science at the Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México, reported that in the last four months of 2009, only 30 of 124 front-page stories did not directly or indirectly criticize the Kirchners.3 The turning point in the Kirchner-Clarín relationship came in 2008 when recently-elected President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner approved a tax increase on farm exports, which resulted in a widespread strike by the agricultural sector. Clarín, one of the main organizers of the nation’s largest annual agricultural fair, sided with the striking farmers, leading the Kirchners to break their alliance with the media conglomerate and to begin the battle that today is raging fiercer than ever.

Three years ago, the Argentine Congress passed the contentious Law 26.522 of Communication and Audiovisual Services. After a continuous onslaught of appeals and legal battles between Clarín and the government, the media law will finally go into effect on December 7. According to the national government’s official website, the law intends to prevent the formation of media monopolies by restricting the number of licenses that can be held by any one media group to 24, significantly less than the 250 licenses currently held by Clarín.4 After 7D, the government will strip Clarín of its excessive licenses and then redistribute them to new media operators through a public auction.

Fighting for Control

Before deciding which camp is truly on the side of media freedom, it is necessary to define one of the principal threats to that freedom –– censorship. According to “Buying the News: A Report on Financial and Indirect Censorship in Argentina,” a publication by the Open Society Justice Initiative, there are two main kinds of indirect censorship: the concentration of media ownership and the discriminatory allocation of official advertising.5 Neither Clarín nor the government is completely innocent; both are guilty of at least one of these two types of censorship, which are actually intimately connected.

When media ownership –– such as Clarín’s –– is concentrated among only a few groups, smaller media outlets are often suppressed or, on occasion, forced out of business by the larger media conglomerates in the competition for limited advertisement revenue ––effectively silencing the voices of critical niche, alternative, and cultural sectors of society. At this point, governments will often step in to alleviate the financial difficulties of smaller media outlets through the discretionary distribution of public advertising. An Organization of American States human rights expert, Eduardo A. Bertoni, has warned that “the possibility of discretionary decisions, without clear rules as to whom and how official advertising is granted, opens the door to arbitrariness.”6 It is this element of “arbitrariness” that often transforms what once began as a method to maintain the diversity and freedom of expression into a way of gaining indirect control over the media through financial pressure.

By the Numbers: National Distribution of Public Advertising

This year, an independent Argentine research agency published a study regarding the distribution of government-sponsored advertising in print media. It revealed that, during the first quarter of 2012, total government spending on public advertising in print publications increased by 87 percent as compared to the same period in 2011 –– from 70 million to 130 million Argentine pesos. This figure took into account inflation but did not consider future printing tariff discounts.7

Given the major rivalry between Clarín and the national government, it is not surprising that the media conglomerate saw a 61 percent reduction in public advertising revenue in 2012 as compared to the previous year.8 Other national media dissidents, including the publishing groups La Nación and Editorial Perfil, also lost public advertising during the same time period at a clip of 96 percent and 42 percent, respectively.9 On the other hand, media groups that have presented more favorable coverage of the current administration received varying increases in government financial support through official publicity. The largest national beneficiaries were Grupo Veintitrés (up 114 percent), Grupo Uno (up 847 percent), and Grupo Televisa (up 3597 percent). Both Grupo Veintitrés and Grupo Uno received over 20 million pesos each, approximately $4.2 million USD, in revenue from government advertising during the first quarter of 2012.10 Despite its status as the largest mass media group in Latin America, the powerful Mexican media conglomerate Grupo Televisa experienced the greatest relative increase in government advertising after its recent purchase of Editorial Televisa. Such massive support could set a self-defeating precedent in Kirchner’s monopoly-based argument against Clarín.

With the rise of the digital news age, the role of advertising income in media, especially in print publications, has become increasingly important. In 2010, the federal government surpassed Unilever and Procter & Gamble to claim the title of Argentina’s principal advertiser, accounting for nine percent of the total market.11 For smaller publications, especially local media in the Argentine interior provinces, the presence or absence of government advertising often represents the difference between survival and death. Many provincial governments, regardless of party affiliation, will exploit this dependency, using public advertising as a financial prize or punishment. For example, media outlets in the southern Tierra del Fuego province receive almost three-quarters of their advertising revenue from government agencies. Five journalists, a radio station owner, a provincial official, and a municipal official all confirmed to the organization Open Society that through the purchase of advertising, the government gains control over who the media outlet interviews.12

On the other side of the spectrum, one finds the media conglomerate Clarín which does not currently receive significant revenue from government sponsored advertisements. With an expansive readership, Grupo Clarín’s flagship newspaper, Clarín, has the greatest circulation of any newspaper in Latin America and the second highest of any Spanish newspaper in the world. High readership and international recognition are an important part of how the media company attracts more than enough private advertising to sustain its growth.13 However, if Clarín is forced to shed more than 200 of its licenses, as required by the new media law, it will be interesting to see not only how the company’s advertising revenue will be affected but also the broader impact of the law on the nation.

Collateral Damage

President Cristina Kirchner and Grupo Clarín represent two of the most powerful entities in Argentina. Thus, the reverberations from every strike they launch against one another can be felt throughout the rest of the country. More often than not, those caught in the crossfire tend to be innocent bystanders. While Argentine citizens and journalists in general are not directly involved in the conflict, they certainly bear the brunt of the clash over media control.

Extreme accusations, such as “liar,” “mafioso,” and even “Nazi,” have been hurled around by both the government and the media. Both institutions risk losing credibility and the confidence of the Argentine public, if they have not done so already. The polarized atmosphere has forced many journalists to censor themselves, fearing the interpretation of their reporting by those in power. A journalist with La Nación, Laura Zommer, told the Committee to Protect Journalists that when “everyone is a friend or an enemy, many prefer to stay quiet.”14 Argentine journalists’ ability to report objectively is further hindered by partisanship. Those considered “enemies” of the government are not invited to cover public events, officials will not answer their questions at press conferences, the government will often launch smear campaigns against them that severely damage the journalists’ credibility and reputation, and they will often lose sources who fear government retaliation.15

The result of 7D is likely to play a large part in determining the future of the Argentine media. The dismantling of Clarín, purportedly in the name of press freedom and diversity of information, is increasingly difficult to interpret as anything more than a government smokescreen to keep hyper-critical media in check. Kirchner’s administration has emphasized the importance of 7D for the freedom of the press in Argentina, highlighting its potential to even the playing field for smaller media outlets and make the industry more competitive. However, in light of government-sponsored advertising’s significant role in the current Argentine media milieu, Law 26.522 alone will not lead to a freer press. The new media law must be accompanied by legislation that clearly and precisely defines the boundaries for the allocation of government funds through the purchase of public advertising, thus preventing, through criminalization, any kind of preferential distribution. Until now, Clarín’s massive size has insulated it against the desolate financial climate facing most media outlets in recent years, allowing it to thrive without depending upon government support. Nevertheless, if 7D is executed as it stands, the media conglomerate will be severely weakened and possibly unable to provide Argentines with an alternative to news outlets guided by the heavy hand of government-sponsored advertising.

Gabriela Garton, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Please accept this article as a free contribution from COHA, but if re-posting, please afford authorial and institutional attribution. Exclusive rights can be negotiated.

_______________

Sources:

1Sara Rafsky, “In government-media fight, Argentine journalism suffers,” Committee to Protect Journalists, September 27, 2012.

2Jerónimo Repoll, “Política y medios de comunicación en Argentina. Kirchner, Clarín y la Ley,” Andamios, Vol. 7 No. 14 (September-December 2010): 35-67.

3Ibid.

4“7D: la Justicia ordena cumplir la Ley de Medios,” Official Website of the Government of Argentina, October 2, 2012, http://www.argentina.ar/temas/ley-de-medios/927-7d-la-justica-ordena-cumplir-la-ley-de-medios.

5Buying the News: A Report on Financial and Indirect Censorship in Argentina, New York: Open Society Institute, (2005).

6Ibid.

7José Crettaz, “El Gobierno gasta más en publicidad y privilegia a los medios afines,” La Nación, June 11, 2012, http://www.lanacion.com.ar/1481061-el-gobierno-gasta-mas-en-publicidad-y-privilegia-a-los-medios-afines.

8Sara Rafsky, “In government-media fight, Argentine journalism suffers,” Committee to Protect Journalists, September 27, 2012.

9José Crettaz, “El Gobierno gasta más en publicidad y privilegia a los medios afines,” La Nación, June 11, 2012, http://www.lanacion.com.ar/1481061-el-gobierno-gasta-mas-en-publicidad-y-privilegia-a-los-medios-afines.

10Ibid.

11Sara Rafsky, “In government-media fight, Argentine journalism suffers,” Committee to Protect Journalists, September 27, 2012.

12Buying the News: A Report on Financial and Indirect Censorship in Argentina, New York: Open Society Institute, (2005).

13Rebecca Martin, “An epic media battle in Argentina,” DOHA Centre for Media Freedom, August 6, 2011, http://www.dc4mf.org/en/content/epic-media-battle-argentina.

14Sara Rafsky, “In government-media fight, Argentine journalism suffers,” Committee to Protect Journalists, September 27, 2012.

15Ibid.

See Also: